Betting on Things That Never Change

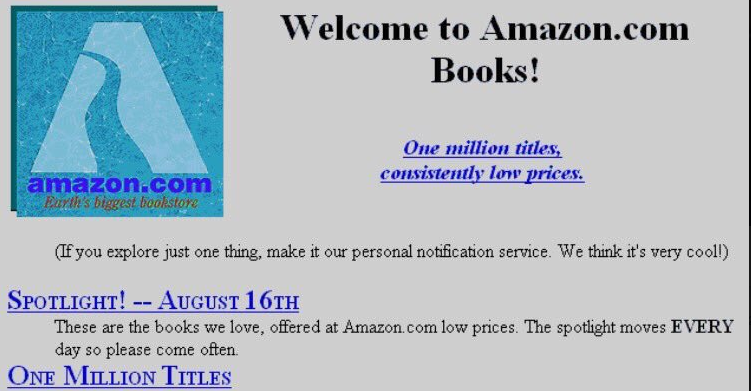

Amazon launched 22 years ago this week.

Its first web page shows its early days:

What’s neat about this isn’t what’s changed. It’s what’s stayed the same.

The line, “One million titles, consistently low prices” seems like marketing guff. But it helps explain why Amazon has dominated where others have failed.

The allure of the Internet in 1995 was betting on change. New paradigms born. Old strategies discarded. Something requiring radically different thinking.

Yet Amazon’s focus from day one was as old as it gets. Selection and price. Businesses have pursued the idea for millennia.

Jeff Bezos once explained why this was critical:

I very frequently get the question: “What’s going to change in the next 10 years?” That’s a very interesting question.

I almost never get the question: “What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?” And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two.

You can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. In our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection. It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, “Jeff I love Amazon, I just wish the prices were a little higher.” Or, “I love Amazon, I just wish you’d deliver a little slower.” Impossible.

So we know the energy we put into these things today will still be paying off dividends for our customers 10 years from now. When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

This is one of those important things that’s too basic for most smart people to pay attention to.

***

Things that change are amazing. They can fuel massive growth.

But change by itself is hard. Investors have to spot it before it’s obvious. Consumers have to change their behaviors to make it viable. Those two points repel each other like magnets. And things that change tend to keep changing. A company whose pitch is “We’re doing this entirely new thing” likely has to reinvent itself and its product line every year, maybe more. Each iteration is a front-line battle where you’re exhausted from the last war but overconfident from its victory. So the odds keep stacking against you. An investor hoping to ride successive changes in multiple industries over a 40-year career faces tenth-degree difficulty. Practically a claim of clairvoyance.

Change often creates bursts of opportunity. Huge opportunity, yes. But businesses and their investors need more than slippery bursts to succeed. They need endurance. And endurance resides in long-term bets. Things you can pour energy and capital into today with a reasonable chance of still bearing fruit ten years from now. Which tend to be things that are stable in time.

This might seem heretical to venture capital. Marc Andreessen was once asked how his investment style compared with Warren Buffett. He replied:

[Warren is] betting against change. We’re betting for change. When he makes a mistake, it’s because something changes that he didn’t expect. When we make a mistake, it’s because something doesn’t change that we thought would. We could not be more different in that way.

Seems directionally true. But I don’t think it’s that black and white. Both investors pursue the same things; they just weight them differently.

Every successful investment is some combination of change that drives competition and things staying the same that drives compounding. There are so few exceptions to this, regardless of size or industry.

Buffett has owned GEICO stock since 1951. During that time the company went from exclusively selling auto insurance to government employees in cafeterias, to selling several kinds of insurance to everyone on their iPhones. Analytics went from abacus to AI. These are not small changes. But one thing stayed the same, which is that an insurance company selling directly would have a cost and convenience advantage over those paying brokers. That’s been the driver of Buffett’s GEICO bet for 66 years. It’s timeless.

Andreessen Horowitz partner Frank Chen recently talked about two trends in insurance startups. One is better software. “Software will rewrite the entire way we buy and experience our insurance products,” he said. Second is capital structure. “We expect to see more crowdsourced insurance companies … it should be a cheaper way to pool capital.” Both innovations promise lower cost and added convenience. Which is as timeless as GEICO’s edge.

Investors weigh the importance of change and timelessness differently, but every great company has some element of both. The extremes are where things don’t work.

Take three companies in the 1990s: Sears, Beenz, and Amazon.

Sears bet the Internet changed nothing, to its detriment. Beenz bet the Internet changed everything – creating a points-based currency valid only at online merchants – to its detriment. Amazon bet the Internet changed distribution, but rooted its strategy in things that have never, and will never, change. It nailed the center of the Venn diagram of change on one side and timeless on the other. One drove competition, the other drove compounding. Every successful company does this.

***

In the last 100 years we’ve gone from horses to jets and mailing letters to Skype. But every sustainable business is accompanied by one of a handful of timeless strategies:

-

Lower prices.

-

Faster solutions to problems.

-

Greater control over your time.

-

More choices.

-

Added comfort.

-

Entertainment/curiosity.

-

Deeper human interactions.

-

Greater transparency.

-

Less collateral damage.

-

Higher social status.

-

Increased confidence/trust.

You can make big, long-term bets on these things, because there’s no chance people will stop caring about them in the future.