Consumer Fatigue and The Brand Cycle

Brand loyalty, like everything else, is cyclical.

In the 1920s it was, unsurprisingly, at a nadir.

Then, encouraged by the New Deal, consumerism rallied in the succeeding decade; however, brand sentiment remained weak as companies, still reeling from the Great Depression, lacked necessary budgets to promote brands.

The 1940s saw a resurgence of brand, as advertisers played a leading role in the ideological activation of the public in World War II and redefined the “American Way of Life” in terms of a capitalist commitment to free enterprise.

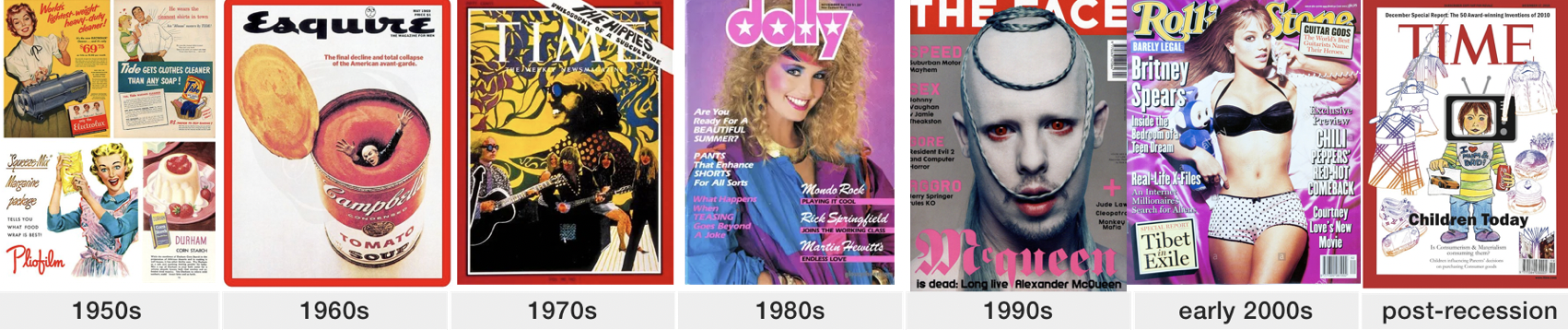

Driven by the Golden Age of Advertising and the popularization of television, the prosperous postwar era of the 1950s was a brand heyday.

The hippies of the 1960s and 1970s eschewed brands, in part reacting to the capitalist excesses of the previous decades.

The 1980s ushered in an age of Big Brands, thanks to cable television (especially MTV and QVC) and the cultural lionization of boldness (in colors, personalities, and displays of wealth).

Then brands were summarily rejected once again in the 1990s as punk rockers and their impersonators opted for logo-less white t-shirts and ripped jeans.

The early aughts, buoyed by a financial boom and the birth of the imitable Internet celebrity, was a time of overt garishness when luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Juicy Couture ascended to new heights, only to collapse spectacularly in the recession during a period of acute consumption anxiety.

That brings us to the 2010s – a time when consumers not only paid high premiums for brand, but also began self-identifying with those brands; a time when consumers have slowly become brands themselves.

It’s no coincidence that the latest bump of brand loyalty dovetailed with the popularization of Instagram and our collective obsession with image.

The growth of online shopping and other social media platforms also contributed, as consumers could establish direct relationships and emotional, though transparently artificial, connections with brands.

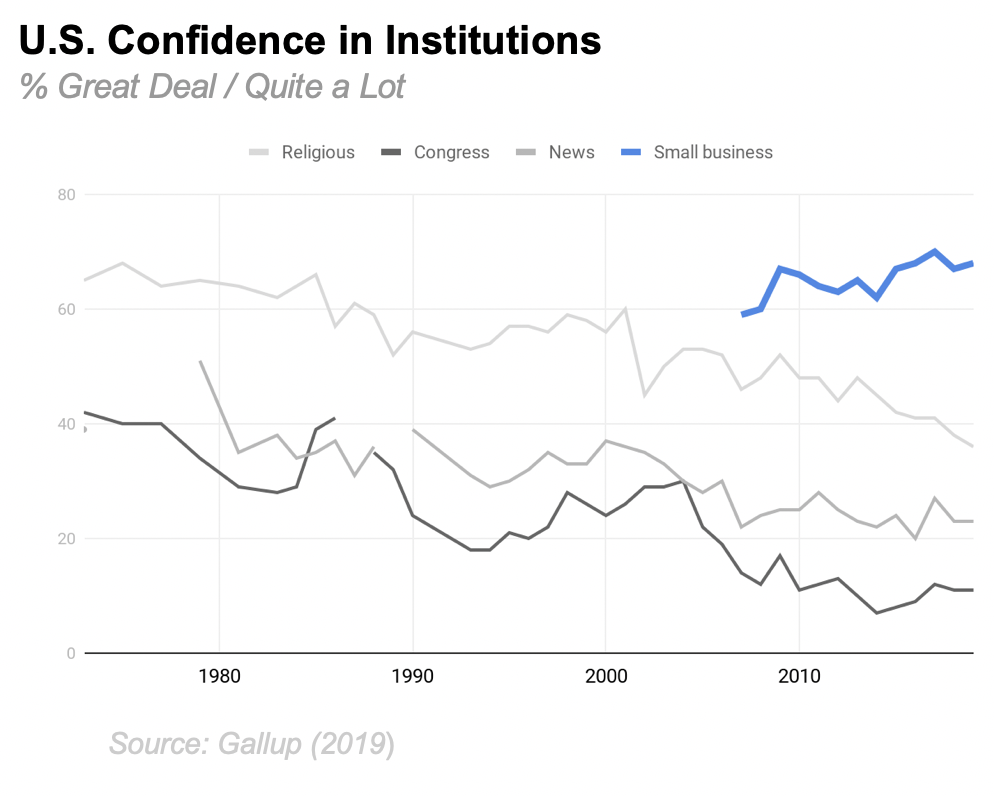

With the abject failure of religious, political, and other social institutions, consumers turned to brand labels as a means to subtly signal values to other like-minded individuals and build proxy communities. When a consumer walks around with a subtly branded tote bag, coffee cup, or pair of bamboo sneakers they are easy to identify by other exercise, coffee, or environmental enthusiasts.

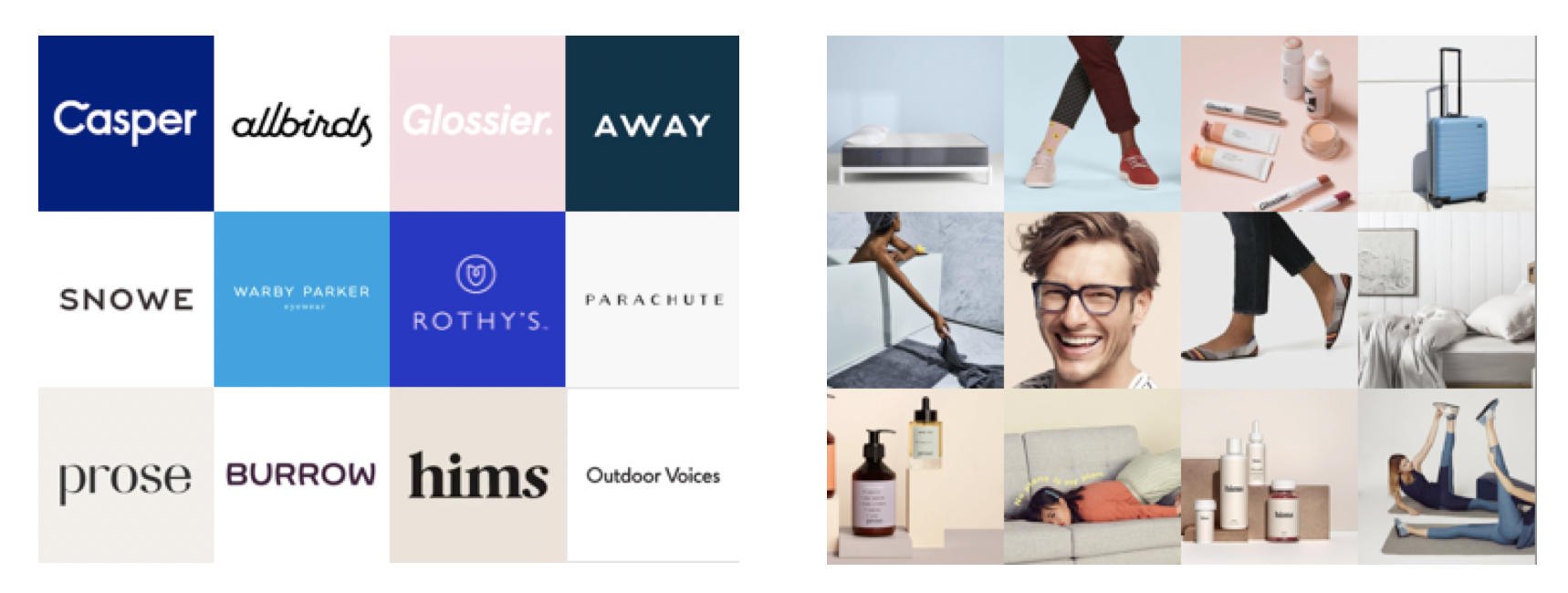

This is why so news outlets love to refer to e-commerce startups as “cult-brands”.

But this brand boom has been remarkable compared to previous cycles, and not entirely positively. Although brand is at a premium, brands themselves are barely distinguishable.

Through the merging of the individual self with the corporate brand, an anesthetized type of branding, sometimes referred to pejoratively as “blanding”, has emerged with nondescript, barely-visible logos, flat studio-lit backgrounds, soothing neutral colors, and fresh-faced models – a minimalist aesthetic primed to blend in with one’s personal brand image.