Here We Are: 5 Stories That Got Us To Now

Three days after Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in 1981, New York City Council President Carol Bellamy joined a group of speakers at a luncheon to discuss the country’s future.

The group tried to make sense of a world that was hardly recognizable from a generation before. Crime, inflation, and unemployment were surging. Speakers offered visions of what might happen next.

Bellamy said they were all misguided.

No one was discussing “where we’ve been, and until we know that, it’s difficult to figure out where we’re heading,” she said, according to the New York Times.

This article is about how that idea applies to 2020.

Everyone is innocently short-sighted when trying to make sense of 2020.

January, before Covid-19 upended everything, feels like a different lifetime. March is already a blur. Time slows when you experience surprise, and every day of 2020 brings a new shock. So the recent past feels like distant history.

But if you survey the confusing mess we’re in – 50 million jobs lost, 130,000 dead, Tesla stock up 400% – you have to remember that none of it happened in a vacuum. Every event has parents, grandparents, siblings, and cousins – previous events that planted the seeds, passed on their DNA, and continue to influence what’s happening today.

To have any hope of making sense of what’s happening in 2020, we have to pay attention to a bunch of seemingly unrelated stories that began before anyone had heard of Covid-19.

Here are five that seem particularly important.

1. People grew apart financially at the same time they became connected digitally, which exacerbates tribal instincts and exposes you to people who don’t see the world as you do, who become easy targets for criticism and blame.

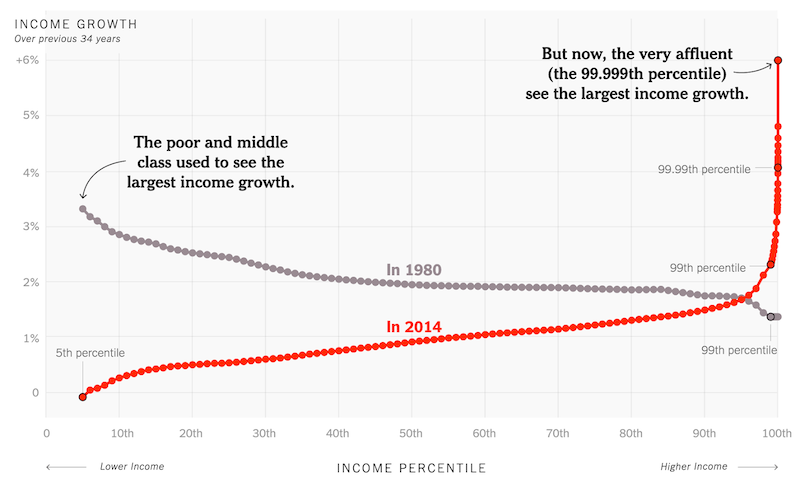

To understand why so many people are so angry in 2020 you have to realize that half the country gained insight into the other half at the very moment those halves were as different economically as they’ve ever been.

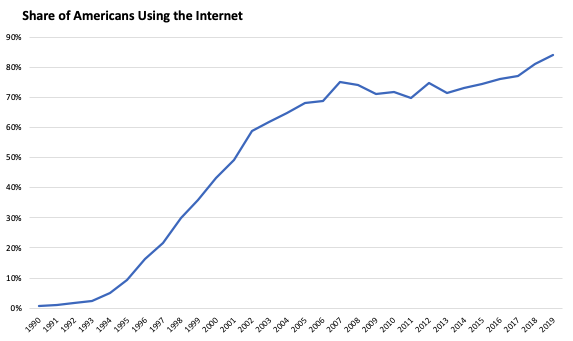

Here’s one side of the equation:

And the other:

These well-known stories are usually viewed in isolation. It’s how they interact with each other that I find interesting.

There are a few parts to it:

-

People gauge their wellbeing relative to those around them.

-

Historically, the people around you were relatively similar to you. They lived in the same city, went to the same schools, worked at the same factories, and earned similar wages.

-

The internet and social media increased the number of people “around you” exponentially.

-

It happened at the same time the economic distance between people ballooned.

It’s important, because when you’re exposed to people who are experiencing a different world than you are it becomes easy to ask, “Why don’t I have what they have?” on one end and, “Why don’t they have what I have?” on the other. Or just, “Why are you not like me?”

People have always asked that question. But the range of answers isn’t wide if the pool of people you judge yourself against is constrained to the town you live in or the company you work for. Once it’s expanded to 2.6 billion people commenting on Facebook posts, or a curated feed of Instagram vacation photos from Dubai and the Maldives, you enter a different world.

It pours gasoline on the flame of two things.

One is that the lifestyle of legitimately wealthy people inflates the aspirations of lower-income families, pushing them towards funding an equivalent lifestyle that can only be achieved with ever-growing amounts of debt. This is true for everything from houses to cars to college degrees.

Another is that people whose lives have taken different paths will have different views on everything from politics to cultural norms. When those groups are then exposed to each other, it can be hard to distinguish a differing view from a threatening view. Disagreements ensue, embolden by the anonymity and detached nature of social media. TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington recently wrote: “I thought Twitter was driving us apart, but I’m slowly starting to think half of you always hated the other half but never knew it until Twitter.”

Harper’s Magazine wrote in 1957 about the leveling forces of the prosperous middle class:

The rich man smokes the same sort of cigarettes as the poor man, shaves with the same sort of razor, uses the same sort of telephone, vacuum cleaner, radio, and TV set, has the same sort of lighting and heating equipment in his house, and so on indefinitely. The differences between his automobile and the poor man’s are minor. Essentially they have similar engines, similar fittings. In the early years of the century there was a hierarchy of automobiles.

It’s interesting to ask: what would social media be like in that era compared to this one?

It would lead to disagreement. But with the same fervor as today? Probably not.

It would be nasty. But as nasty as today? Probably not.

But we have it today. So here we are.

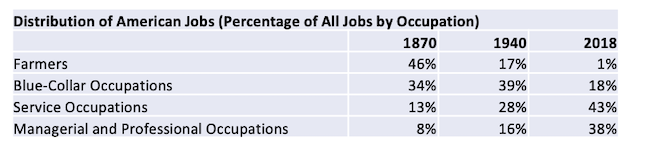

2. A century-long shift away from labor-intensive jobs towards creative-thinking jobs creates a stark contrast between jobs that can be done during a pandemic and jobs that can’t.

For most of history people worked with their arms, legs, and backs. They labored.

The machines came along and more people started working with their hands, operating equipment in factories.

Then computers came along and more people started working with their brains, doing creative and service jobs.

It isn’t a subtle shift. It’s been a complete remake of the economy in modern times:

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

It’s an important shift for many reasons.

For most of the 20th Century the idea of working from home was not an option. People worked in factories and shops, and there was no alternative because working meant doing something with your muscles, usually around other people.

So when there was a common disaster – like a pandemic – virtually everyone faced the same circumstances. If business had to be kept open, all businesses had to be kept open, and all occupations faced the threat of catching the disease at work. If businesses had to be shut, all businesses had to be shut. Nothing could be shifted to a daily Zoom call.

John Barry writes in his book on the 1918 flu pandemic:

At virtually every large employer, huge percentages of employees were absent … Farmers stopped farming and the merchants stopped selling merchandise and the country really more or less just shut down holding their breath … The entire transportation system for the mid-Atlantic region staggered and trembled, putting in jeopardy most of the nation’s industrial output.

It’s very different today.

Compare the plight of a local restaurant with, say, Facebook. One is shut down, unable to operate without in-person service. The other can get along just fine with its entire workforce working from home.

Same if you contrast food processing plants with tax consultants.

Or American Airlines with American Express.

We are lucky that a lot of today’s economy can shift seamlessly into remote work. It wouldn’t have been possible to this extent if Covid-19 struck in 2010 instead of 2020.

But it again sets up a stark contrast of haves and have nots, and groups of people who are experiencing Covid-19 in different ways.

Massachusetts did a survey in April that tells the story:

-

88% of those with an advanced degree can work from home, vs. 35% with a high school degree or less.

-

75% of those making more than $150,000 a year can work from home, vs. 44% of those earning less than $50,000 a year.

-

74% of salaried workers can get their jobs done from home, vs. 40% of hourly workers.

There is a long history of economies being hit with downpours. But this is the first in which perhaps 70% of the economy has a sturdy umbrella while 30% is left to get soaked.

It removes a “we’re-all-in-this-together” aspect of the crises that’s key to recovery. It’s not easy to get everyone to cooperate when Covid-19 is a petty annoyance to some and a catastrophe to others. But that’s what we have now. So here we are.

3. Things have been pretty good for a long time. So a setback, even if it’s not unprecedented, feels overwhelming.

“Everything feels unprecedented when you haven’t engaged with history,” writer Kelly Hayes recently wrote.

It’s such a relevant idea today.

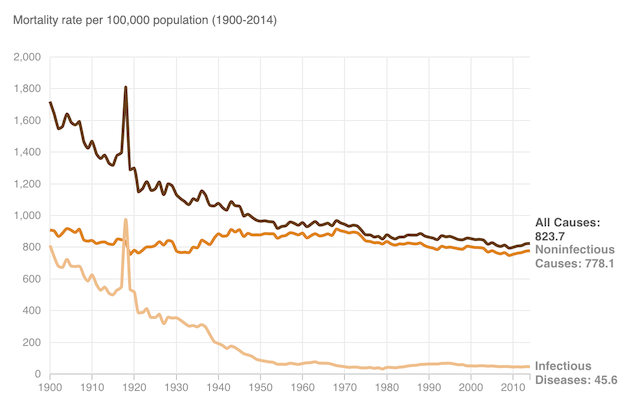

Historian Dan Carlin writes in his book The End is Always Near:

Pretty much nothing separates us from human beings in earlier eras than how much less disease affects us … If we moderns lived for one year with the sort of death rates our pre–industrial age ancestors perpetually lived with, we’d be in societal shock.

In 1900 roughly 800 per 100,000 Americans died each year from infectious disease. By 2014 that was 45.6 per 100,000 – a 94% decline.

Life in general is about as safe as it’s ever been. And effectively all of the improvement over the last century has come from a decline in infectious disease:

This decline is probably the best thing to ever happen to humanity.

To follow that sentence with “but” is a step too far. It’s a wholly good thing.

However, it creates an anomaly.

We are medically more prepared to fight disease than ever before. But, psychologically, the mere thought of a pandemic has never felt so foreign, so unprecedented, so upending.

What was a tragic but expected part of life 100 years ago is now a tragic and inconceivable part of life in 2020.

Clark Whelton, a former speechwriter for New York mayor Ed Koch, recently wrote:

My mother once showed me a list of the contagious diseases she survived before the age of 20. On the list were the usual childhood illnesses, along with deadly afflictions like typhoid fever, pneumonia, diphtheria (it killed her older brother), scarlet fever, and the lethal 1918–19 Spanish flu, which took more than 50 million lives around the world.

For those who grew up in the 1930s and 1940s, there was nothing unusual about finding yourself threatened by contagious disease. Mumps, measles, chickenpox, and German measles swept through entire schools and towns; I had all four. Polio took a heavy annual toll, leaving thousands of people (mostly children) paralyzed or dead. There were no vaccines. Growing up meant running an unavoidable gauntlet of infectious disease. For college students in 1957, the Asian flu was a familiar hurdle on the road to adulthood. For everyone older, the flu was a familiar foe. There was no possibility of working at home. You had to go out and face the danger.

4. Local news gave way to national news which gave way to global news, which can make the world feel perpetually broken because there is always a tragedy somewhere, and now you are guaranteed to hear about it.

Historian Frederick Lewis Allan describes how Americans stayed informed in the year 1900:

It is hard for us today to realize how very widely communities were separated from one another when they depended for transportation wholly on the railroad and the horse and wagon–and when telephones were still scarce, and radios non-existent.

There were sharp limits to the fund of information and ideas which people of all regions and all walks of life held in common. To some extent a Maine fisherman, an Ohio farmer, and a Chicago businessman would be able to discuss politics with one another, but in the absence of syndicated newspaper columns appearing from coast to coast their information would be based mostly upon what they had read in very divergent local newspapers.

Information was harder to disseminate over distances, and what was going on in other parts of the country or the world just wasn’t your top concern – information was local because life was local.

We shouldn’t be surprised that the world feels historically broken in recent years. It’s not – we just see more of the bad stuff than ever before.

5. The Federal Reserve learned how to keep the financial system from falling apart. That’s both kept a lot of the economy humming and ruined a lot of assumptions people had about how the economy works.

In 2002, former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke gave a speech at Milton Friedman’s 90th birthday.

Friedman, one of the most influential economists of the 20th century, spent his career arguing that the Fed caused the Great Depression by not preventing a decline in the money supply.

Bernanke ended his talk by saying:

I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it.

We’re very sorry.

But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.

It was a joke, but he wasn’t joking.

In 2008 Bernanke, as Fed chairman, flooded the financial system with an unprecedented amount of liquidity.

It worked, which is why we call 2008 the Great Recession and not the Second Great Depression.

It also paved the way for Bernanke’s successors to open the monetary floodgates when the economy tumbles.

Jerome Powell, Bernanke’s successor, injected more than $4 trillion into the financial system between September and June. That’s double what Bernanke did in 2008. In March and April this year the Fed bought more than 100% of all mortgage-backed securities issued, meaning it funded roughly all new mortgages and purchased billions more from existing investors.

Bernanke was given flak for cutting interest rates in 2008. Powell is now buying corporate-bond ETFs in the open market.

Things have changed.

And they’re probably not going back, because people have a new set of expectations about what the Fed can and should do.

The Fed is 107 years old. It seems like a long time. But it’s only been able to learn from two or three deep financial crises during its existence, which isn’t many. So it’s basically just now learned what to do when the economy tanks.

That’s a big deal, because a lot of what we thought we know about what economies do during recessions has been upended.

Josh Brown recently wrote:

Generations of investors had been taught that, in a bear market, the most gruesome casualties would be the highest-flying, most expensive stocks. This time, the experience has been the opposite. There are a lot of “textbook” ideas that won’t survive coronavirus and this is one of them.

When interest rates are zero and liquidity floods the market, the value of a company’s future cash flows rises. That’s the technical part. The interesting part is that when future cash flows become more valuable, the stories that lead people to believe in the prospect of future cash flows become more important. That’s part of how Tesla becomes worth $300 billion, or Nikola becomes worth $25 billion before it’s made a single car. Stories about what the future might be become more important than what the present actually is.

Or think about the fact that the stock market seems unreasonably high right now – even bubbly – but it’s still dramatically underperformed long-term Treasury bonds over the last 20 years.

It’s hard to make sense of that world. It’s a world that would have seemed unfathomable 20 years ago.

But here we are.