History is Only Interesting Because Nothing is Inevitable

Nothing that’s happened had to happen, or must happen again. That’s why historians aren’t prophets.

Wars, booms, busts, inventions, breakthroughs – none of those things were inevitable.

They happened, and they’ll keep happening in various forms.

But specific events that shape history are always low-probability events. Their surprise is what causes them to leave a mark. And they were surprising specifically because they weren’t inevitable. A lot of things have to go right (or wrong) to move the needle in what is an otherwise random swarm of eight billion people on earth just trying to make it through the day.

The problem when studying historical events is that you know how the story ends, and it’s impossible to un-remember what you know today when thinking about the past. It’s hard to imagine alternative paths of history when the actual path is already known. So things always look more inevitable than they were.

Now let me tell you a story about the Great Depression.

To understand the mood of the late 1920s you have to understand what the country went through a decade prior.

One hundred sixteen thousand Americans died in World War I. Almost 700,000 died from the Spanish Flu outbreak in 1918. As the war and the flu came to an end in 1919, America became gripped by one of its worst recessions of modern times. Business activity fell 38% as the economy transitioned from wartime production to regular business. Unemployment hit 12%.

The triple hit of war, flu, and depression took a toll on morale.

The Wall Street Journal, December 18th, 1920. “The war clouds darken the sky no more, but clouds of business depression and stagnation obscure the sun.”

The Wall Street Journal, April 7th, 1921. “The economic outlook was never so complex as it is now.”

Los Angeles Times, November 11th 1921.

It’s vital to point this pessimism out, because an important part of the late-1920s boom is understanding how desperate people were for good news after a decade of national misery.

As the clouds began to part in the mid-1920s, Americans were so exhausted from what they’d been through that they were quick to grab onto any signs of progress they could find. Historian Frederick Lewis Allen wrote in the 1930s:

Like an overworked businessman beginning his vacation, the country had had to go through a period of restlessness and irritability, but was finally learning how to relax and amuse itself once more. A sense of disillusionment remained; like the suddenly liberated vacationist, the country felt that it ought to be enjoying itself more than it was, and that life was futile and nothing mattered much. But in the meantime it might as well play – following the crowd, take up the new toys that were amusing the crowd.

By 1924 there’s a distinct shift in tone among the business press.

The Baltimore Sun, January 1, 1924:

America had endured more trauma than at any point since the Civil War in a way that left it shaken, scared, and skeptical. By 1928 the final traces of that fear subsided, and its people were ready to embrace the peace and prosperity they wanted so badly. Once secured, they had no intention of letting go and going back to where they were.

On June 18th, 1927 the Washington Post wrote a headline that explains so much of what would took place over the next two years:

One thing that sticks out about the late 1920s is the idea that prosperity wasn’t only alive, but was immortal.

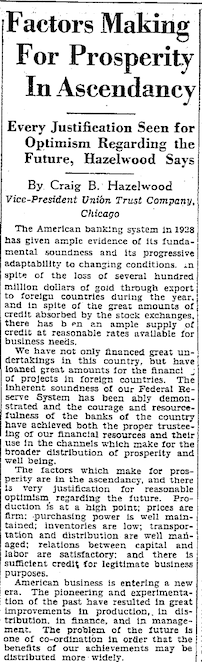

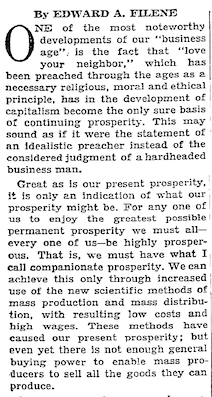

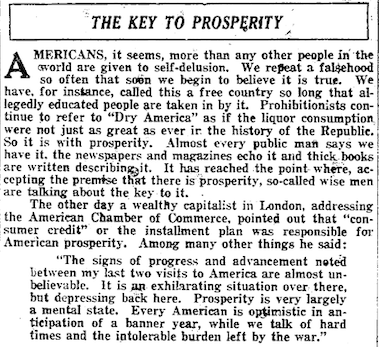

Those promoting this belief were not subtle. The New York Herald, August 12th, 1928:

The Los Angeles Times, December 23rd, 1928:

The Boston Globe, January 2nd 1928:

The Christian Science Monitor, February 27th, 1928:

The notion that recessions had been eliminated is easy to laugh at. But you have to consider three things about the 1920s that made the idea seem feasible.

One is that the four inventions that transformed the 1920s – electricity, cars, the airplane, and the radio, and – seemed indistinguishable from magic to most Americans. They were more transformational to the economy than anything since the steam engine, and changed the way the average American lived day to day than perhaps any other technology before or since. Technology that spreads so far, so fast, and deeply tends to create an era of optimism, and a belief that humans can solve any problem no matter how difficult it looks. When you go from a horse to an airplane in one generation, taming the business cycle doesn’t sound outrageous, does it?

The New York Times, May 15th, 1929:

A second factor that made the end of recessions seem feasible was the idea that World War I was the “war to end all wars.”

The documentary How to Live Forever asks a group of centenarians what the happiest day of their life was. “Armistice Day” one woman says, referring to the 1918 agreement that ended World War I. “Why?” the producer asks. “Because we knew there would be no more wars ever again,” she says.

When you believe the world has entered an era of permanent peace, assuming permanent prosperity will follow isn’t a big stretch.

The Boston Globe, October 6th, 1928:

A third argument for why prosperity would be permanent was the diversification of the global economy.

Manufacturing was to the 1920s what technology was to the 2000s – a new industry with big wages and seemingly endless growth. But unlike technology today, manufacturing was incredibly labor-intensive, providing good jobs for tens of millions of Americans.

A new and powerful industry can create a sense that past rules of boom and bust no longer apply, because the economy has a new quiver in its belt.

The LA Times, January 1st, 1929:

That same day, Chicago Daily Tribune:

Beyond the permanence of prosperity, optimism over technology and its ability to pull rural farmers into the new middle class gave the impression that the gains had barely begun. The Christian Science Monitor, May 15th, 1929:

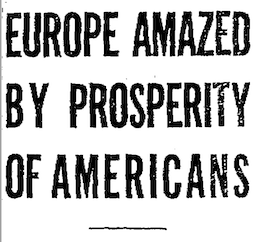

The view was shared outside of the United States. The Los Angeles Times, December 12th, 1928:

Around the world, people wanted a piece of what America had. The Hartford Courant, August 6th, 1928:

The Hartford Courant, May 16th, 1929, described “conditions more or less permanent” and “fears for the future seem increasingly without foundation.”

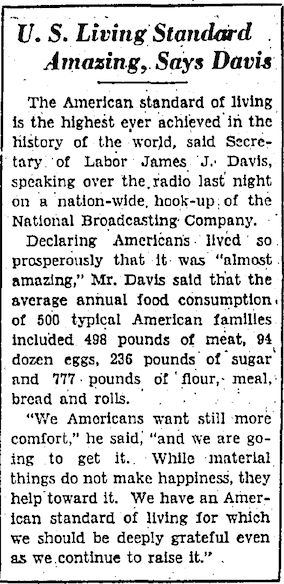

Little things Americans could hardly consider a few years before became reality.

After huge budget deficits to finance the war, government coffers were flush. The New York Times, June 27th, 1927:

Consumer debt, we know in hindsight, was a major cause of the crash and depression. But at the time growing credit was seen as a good, clean fuel. The Washington Post, February 19th, 1929:

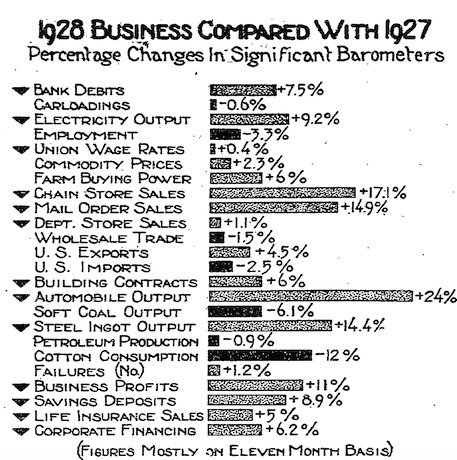

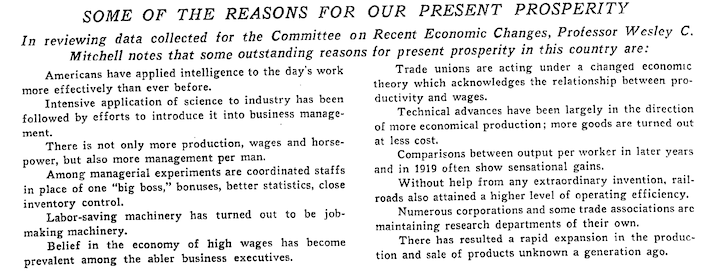

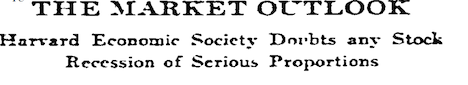

When we look back at the late 1920s we think about crazy stock market valuations and shoe-shine boys giving stock tips. But that’s not what people paid attention to at the time. The newspapers are filled with charts like these: rational, level-headed, and fuel for optimism. The Wall Street Journal, December 31, 1928:

Stocks were surging. But it looked justified, backed by real business values. The Wall Street Journal, March 5th, 1929:

As manufacturing became a driving force of employment, workers discovered bargaining power in a way they never considered before, working on farms. The Washington Post, November 25th, 1928:

Growing middle-class wages seemed to open endless possibilities. The Washington Post, November 13th, 1928:

The New York Times put several of these arguments together on May 12th, 1929:

The New York Herald, January 2nd, 1929:

It’s hard to overstate how transformation these developments were to average Americans, particularly in light of the previous decade’s trauma.

The New York Herald Tribune, October 14th, 1929:

In 1920 Americans were out of work and desperate for a paycheck. Nine years later, the top national goal was promoting leisure time. The New York Herald Tribune September 30th, 1929:

By 1929 the stock market had increased five-fold in the previous decade. Average earnings were at an all-time high. Unemployment was near an all-time low.

Frederick Lewis Allen wrote: “This was a new era. Prosperity was coming into full and perfect flower.”

A popular saying of the day, Allen writes, was “Prosperity due for a decline? Why, man, we’ve scarcely started!” “

It was a party, and no one wanted to stop dancing.

To me the most fascinating part of the 1920s boom is what it did to American culture.

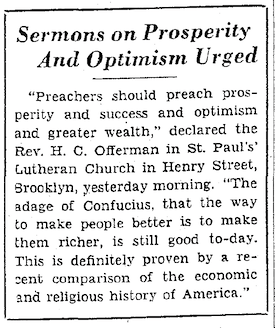

Wealth quickly became the center topic of not just commerce, but values, happiness, and even religion. It took on a new place of importance that didn’t exist in previous generations when it was both lower and more concentrated.

The New York Herald Tribune, February 11th, 1929:

The Baltimore Sun, July 21st, 1929:

Ladies’ Home Journal, June 5th, 1929:

The Washington Post, June 6th, 1928:

The New York Amsterdam News, January 5th, 1928:

The New York Times, August 19th, 1928:

Across the world, heads turned and respect grew. Chicago Daily Tribune, January 28th, 1929:

In just a few years prosperity had taken on a new role in America – not something to dream about, but something that was secured today, guaranteed tomorrow, and sat at the center of what made Americans American.

On September 10th, 1929, The Wall Street Journal wrote:

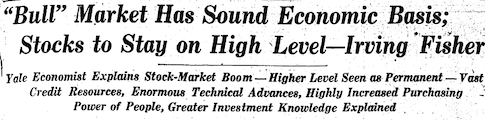

Three weeks later, Irving Fisher made this famous proclamation:

On October 1st, 1929, the Pittsburgh Courier sounded a faint alarm, warning that prosperity was a mental state subject to change:

No one, though, could fathom what was in store next.

The stock market lost a third of its value in the last few days of October, 1929.

The immediate response was shock, but not dread.

On October 26th The New York Times published an article titled, “‘All Well’ is View of Business Chiefs.” It quotes a dozen prominent businessmen:

Arthur W. Loasby, president of the Equitable Trust Company: “There will be no repetition of the break of yesterday. The market fell of its own weight without regard to fundamental business conditions, which are sound. I have no fear of another comparable decline.”

J.L. Julian, partner of the New York Stock Exchange firm of Fenner & Beane: “The worst is over. The selling yesterday was panicky brought on by hysteria. General conditions are good. Our inquires assure us that business throughout the country is sound.”

M.C. Brush, president of the American International Corporation: “I do not look for a recurrence of Thursday and believe that the very best stocks can be bought at approximate present prices.”

R.B. White, president of the Central Railroad of New Jersey: “There is nothing alarming in the situation as regards business. Business will continue the way it had. Plans in the railroad for the future have in no way been changed.”

Three days later the market crashed again. It would not recover its losses until 1954.

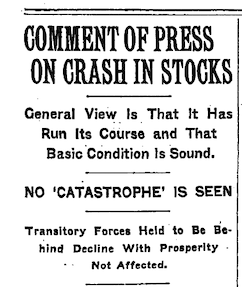

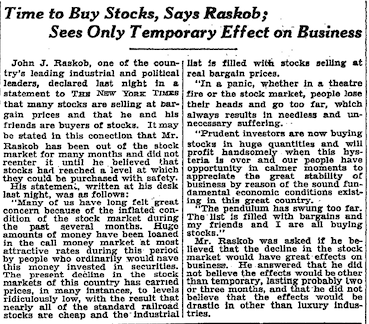

The first response to the crash was to view it as a temporary blip, and permanent prosperity would soon resume. The New York Times, October 30th, 1929:

The Wall Street Journal, October 29th, 1929:

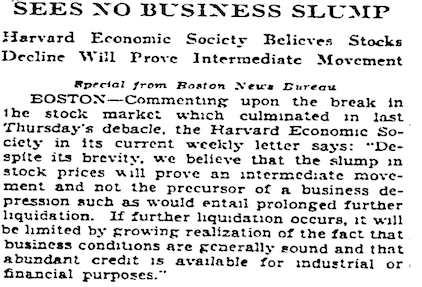

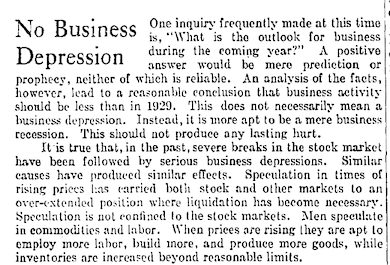

The Boston Daily Globe, October 30th, 1929:

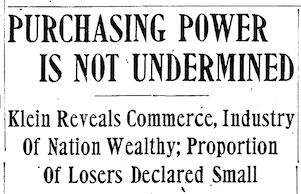

The New York Times, October 30th, 1929:

Barron’s, November 30th, 1929:

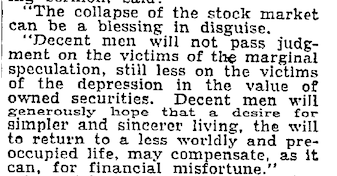

Some saw the crash as a blessing, and an opportunity to simplify life that evolved so quickly in the previous five years. The New York Times, November 13th, 1929:

The Christian Science Monitor, November 25th, 1929:

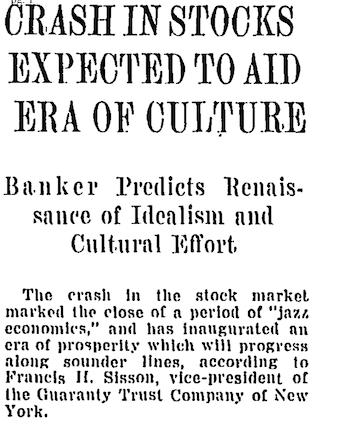

Chicago Daily Tribune, November 26th, 1929:

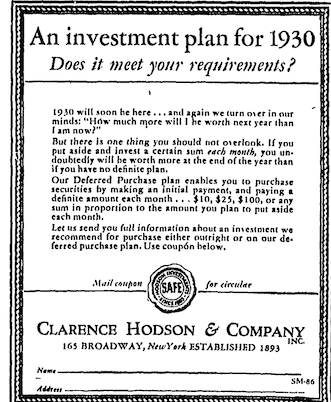

On New Year’s Eve 1929, as a year that began so bright came to such a shocking end, the Wall Street Journal made a friendly reminder: Keep investing, and you’ll undoubtedly have more money a year from now:

Over the next three years the Great Depression put 12 million Americans out of work.

The stock market fell 89%, reverting to levels last seen 36 years prior.

GDP fell 27%.

Prices fell 10% per year.

Nine thousand banks failed, erasing $150 billion in American checking and savings accounts.

Births declined 17%.

Divorce rose by a third.

Suicides rose by half.

The depression gave rise to Adolf Hitler in Germany, setting the course for a world war that would go on to impact nearly every aspect of life we know today.

It was, without question, one of the most consequential events of modern history.

And when we look back at what people were thinking before it began, the question remains:

Did they know?

Did they have any clue?

Were they blind to the inevitable?

Or did they just suffer a terrible fate that wasn’t inevitable?

There has never been a period in history where the majority of people didn’t look dumb in hindsight.

People are good at analyzing and predicting things they know and can see. But they cannot think about or prepare for events they can’t fathom. These out-of-the-blue events go on to be the most consequential events of history, so when we look back it’s hard to understand why few people cared or prepared. The phrase “hindsight is 20/20” doesn’t seem right, because 20/20 implies everything coming into a clear view. In reality, hindsight makes most people look dumber than they actually were.

Whether something is inevitable only matters if people know it’s inevitable. Knowing a decline is inevitable lets you prepare for it before it happens, and contextualize it when it does. The only important part of this story, I hope I have convinced you, is that no one saw the Great Depression as inevitable before it happened.

I don’t think you can call the people of the late 1920s oblivious without answering the question, “Oblivious to what?” A future no one predicted? Consequences no one envisioned? Ignoring advice that no one gave?

At the end of World War II it was assumed by most that, stripped of wartime spending, the economy would slip back into the depths of depression that preceded the war. We know today that it did not – it went on to prosper like never before. So were people oblivious in 1945?

After the stock market crash of 1987, one investor recently recalled, “I remember an uneasy feeling as pundits predicted the start of the next Great Depression and the end of prosperity, as we knew it.” Instead, the 1990s were the most prosperous decade in history. Were we oblivious in 1987, too?

The fact that we avoided depression in 1945, 1987 – and 2009 – might be the best evidence that the actual depression of the 1930s wasn’t inevitable. You can say, “Well, in 1945 the banking system didn’t collapse, and the 1990s were lucky because of the internet,” and so on. But no one in 1945 or 1990 knew those things, just as no one in 1929 knew their future.

It’s not hard to imagine a world where policy responses were a little different, a presidential election tipped a different way, a second world war began a decade before it did, and the economic story of the 1930s playing out differently than it did. But we never get to hear the stories of what could have been or almost was.

We only think something is inevitable if it’s obvious. And things only look obvious when everyone’s talking about them and predicting them.

When you look back at what people said in the late 1920s – their confidence, their clarity, their logic – you can’t help but wonder what we are confident in today that will look foolish in the future.

What those things might be, I don’t know.

It wasn’t obvious in the 1920s.

It won’t be obvious in the 2020s.

That’s what makes history interesting – nothing’s inevitable.