A Simple Guide to the End of the Boom

Few answers to questions have as bad a track record as “What is the economy going to do next?”

That won’t change. Surprises can’t be predicted, by definition, so the gap between predictions and reality will always be wide.

But forecasts are also tripped up by two problems:

-

We’re wooed by complexity and conflate it with added value. As with household products, the more moving parts something has the more likely it is to break.

-

We favor precision over “close enough,” chasing exactly what will happen over a rough idea of the general direction we’re headed.

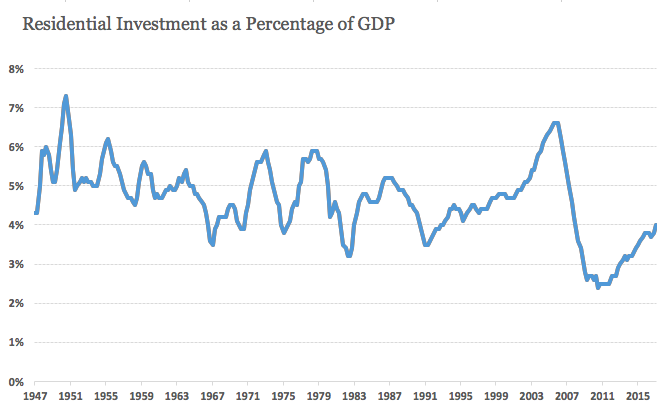

Economist Ed Leamer once tackled both in a paper called “Housing IS the Business Cycle.”

It argues:

-

Residential housing investment has been one of the best indicators of future recessions. It’s big and highly cyclical, giving it an outsized influence on the economy.

-

This isn’t widely accepted by many economists, who prefer deeper theories for why economies do what they do. Leamer writes: “I have not been able to find any macroeconomic textbook that places real estate front and center, where it belongs.”

-

It isn’t a precise forecasting tool. It just explains a big chunk of eight of the last eleven recessions.

This made a forecasting skeptic like me happy. It mixes data with simplicity with humility, which is a rare soup of skills.

So as we sit here a decade since the last recession, stock market up threefold in eight years, trillions of dollars pushing up valuations of all asset classes, I keep asking: What’s happening in residential real estate? Because it may guide us to when this all ends.

Here’s the answer:

We’re still near a level associated with previous bottoms. The only other times since World War II that housing investment has been as low as it is now was during or near recessions. And that’s not because we’ve declined to these low levels, but because the rebound since 2009 has been so meager.

Which is promising. It’s a humble suggestion that we’re not as close to the top of this nine-year expansion as you might think.

The rise of roommate living means there are more than 5 million fewer households than there otherwise would be. The average age at first marriage has risen by almost a quarter in the last 40 years. And more young adults live with their parents than at any other time in history. All of those could push housing investment to a lower norm than the past – which could be why housing investment is so low today.

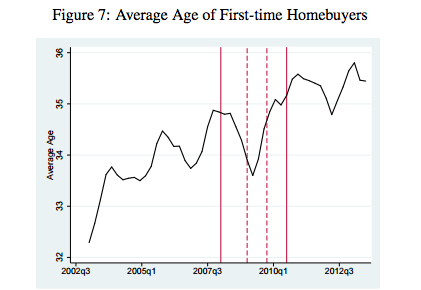

But it could also reflect pent-up housing demand. More jobs being located in cities where it’s expensive to buy and higher college enrollment means the average age of a first-time homebuyer has surged in the last decade:

When the average age of first purchase rises, you should expect there to be a lid on housing investment as the generation who delayed home-buying passes through the age at which the previous generation bought homes.

But the slowdown should catch up once the younger generation ages into their new home-buying years. Millennials delaying homeownership doesn’t mean there’s less need for housing investment. It means the housing market is like a grocery store checkout where the customer stopped putting food on the conveyer belt for a moment. The clerk sees less food coming his way, but there’s still the same amount of food in the cart waiting to be scanned.

Which is to say:

-

Housing investment is a good way to gauge where the economy is heading.

-

It’s currently rising and nowhere near a high level.

-

It’s not hard to argue that it’ll keep rising as millennials age closer to their home-buying years.

It’s terribly simple, and it’s not that precise. But that’s how forecasting should be.