Is CPG Doomed?

What was the last thing you waited in line for?

For your sake, I hope you have a cooler answer than I do, which is that I spent last Saturday sandwiched between carb-conscious hipsters in stylish athleisure wear, diligently waiting, for the better part of an hour, for a bag of frozen cauliflower gnocchi. A Saturday night, no less.

As an erstwhile investor in consumer-packaged goods (CPG) and a lover of all things brand, I never expected to join the Trader Joe’s cult. But when I recently moved to the Lower East Side, within a stone’s throw of a vaulted but relatively new Trader Joe’s – referred to affectionately by those in-the-know (i.e., in-the-cult) as TJs – I quickly fell under its spell.

Quirky seasonal snacks? 19 cent bananas? A never-ending supply of ripe avocados? Sign me up!

If the wilting kale in my fridge (purchased only yesterday) is any indication, then fresh produce is safe. But every time I make the pilgrimage to TJs and am seduced anew by the kitschy branding, low prices, and friendly attendants, I can’t help but wonder: where do other grocery stores and startup CPG brands fit into all of this?

There’s no shortage of criticism we could levy at TJs. Despite mostly successful attempts to cultivate a “neighborhood grocer” vibe, rumors of predatory behavior towards small makers persist. Still, we can’t ignore the beloved space that TJs occupies in the cultural zeitgeist around food, particularly among urban Millennials.

The Rise of Private Label

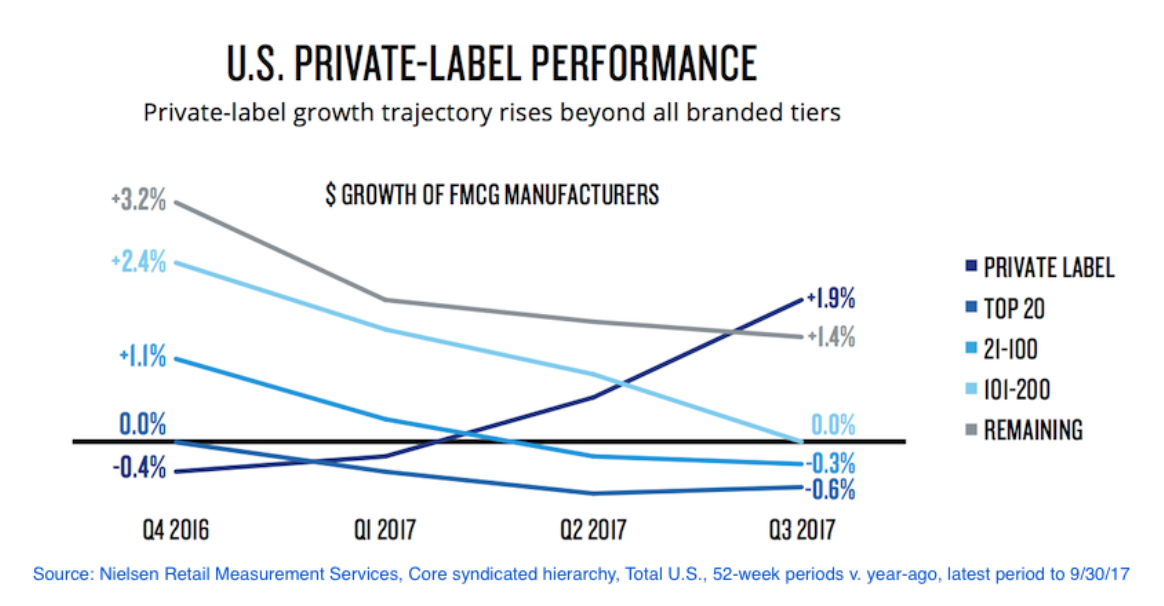

I’m hardly the first person to ponder whether Trader Joe’s is the model for the future of food. Store brands (aka private label brands) have been cannibalizing CPG brands, particularly food and beverage, for the better part of a decade.

U.S. private label sales reached $143 billion in 2018, up over 10% since 2015. While name brand products were up 2% in sales, growth was constrained because consumers are actually much more willing to splurge for store brands than they are for name brands.

According to a 2019 Nielsen survey, 40% of Americans say they would pay the same or more for the right store branded/private label product, while only 26% of those surveyed feel that name brands are worth the extra price. This trend is often referred to as the premiumization of private label – and it has knock-on effects not just for Big Brands but for startups and investors in CPG as well.

Retailers are Getting Better at Branding

Above my Trader Joe’s is a Target, where I am occasionally lured by the sweet promise of my preferred iced coffee brand. While there, I like to wander the aisles and take note of which new CPG startups have snagged a spot on the superstore’s shelves.

Over the past few months, I can’t help but notice how Target is imitating its downstairs neighbor. Week by week, private label spreads, demoting smaller CPG brands to bottom-shelf territory or displacing them entirely.

And what’s more, I don’t think most customers realize it.

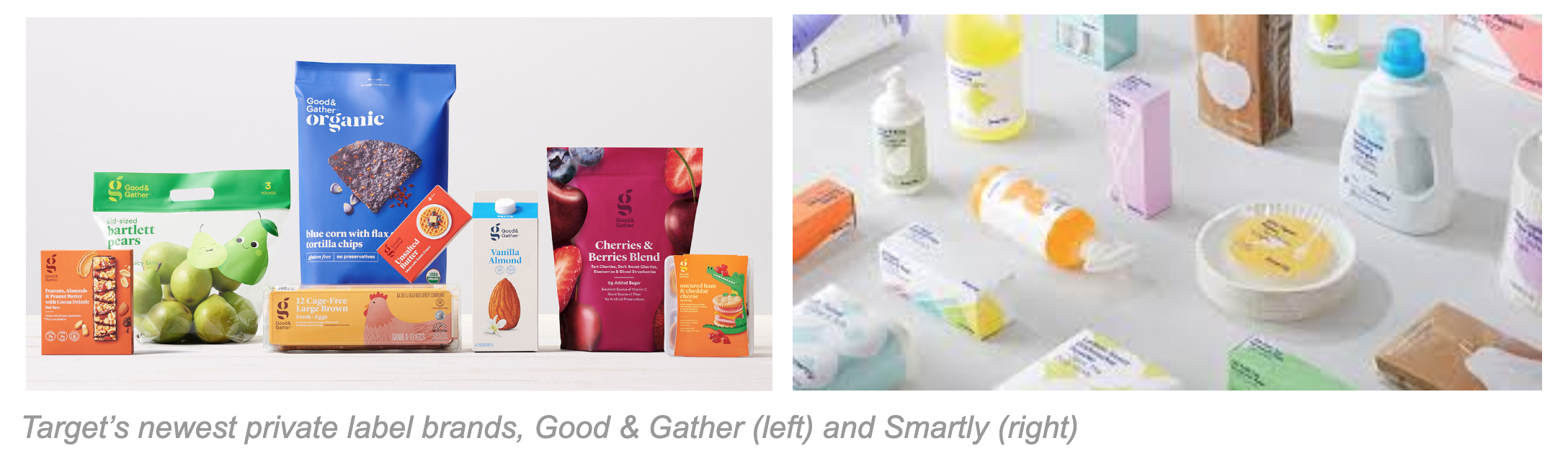

That’s what makes this trend so fascinating and concerning to me. Big Box stores have gotten much better at branding, particularly on the premium end.

It used to be easy to spot store brands with their blanched labels designed to signal “this is fine and it’s cheaper.”

True, the new wave of genially-dubbed store brands – Good & Gather, Nice!, and Smartly – are far from revolutionary, but they draw a consumer’s eye and can go toe-to-toe with many emergent CPG brands, some of which spent over a quarter million dollars with elite NYC branding agencies.

They don’t seem like private label. And it’s not just the packaging.

Private Label Is Catching Up With Trends

Historically, private label won on pricing and preferential shelf placement (or web page placement if we’re expanding our discussion to Amazon), and focused on discount products.

But now retailers are expanding into luxury categories like wine – premium tiers now represent 19% of private label sales – and they’re getting better at packaging and branding? What does that leave for up-and-coming CPG brands?

Storytelling? Maybe; that’s certainly a significant driver of consumer evangelism for TJ products.

But good luck getting Target or Whole Foods to tell your brand’s heartwarming origin story or unique product proposition when they can double their margins by just pushing their house brands front-and-center. You can tell your own story directly to customers, but the efficacy of social media is waning and demos are hardly a scalable solution.

Of course, genuine “product differentiation” is always a covetable moat. But a number of consumer trends that seemed like tailwinds for emerging brands just a few years ago now seem like roadblocks.

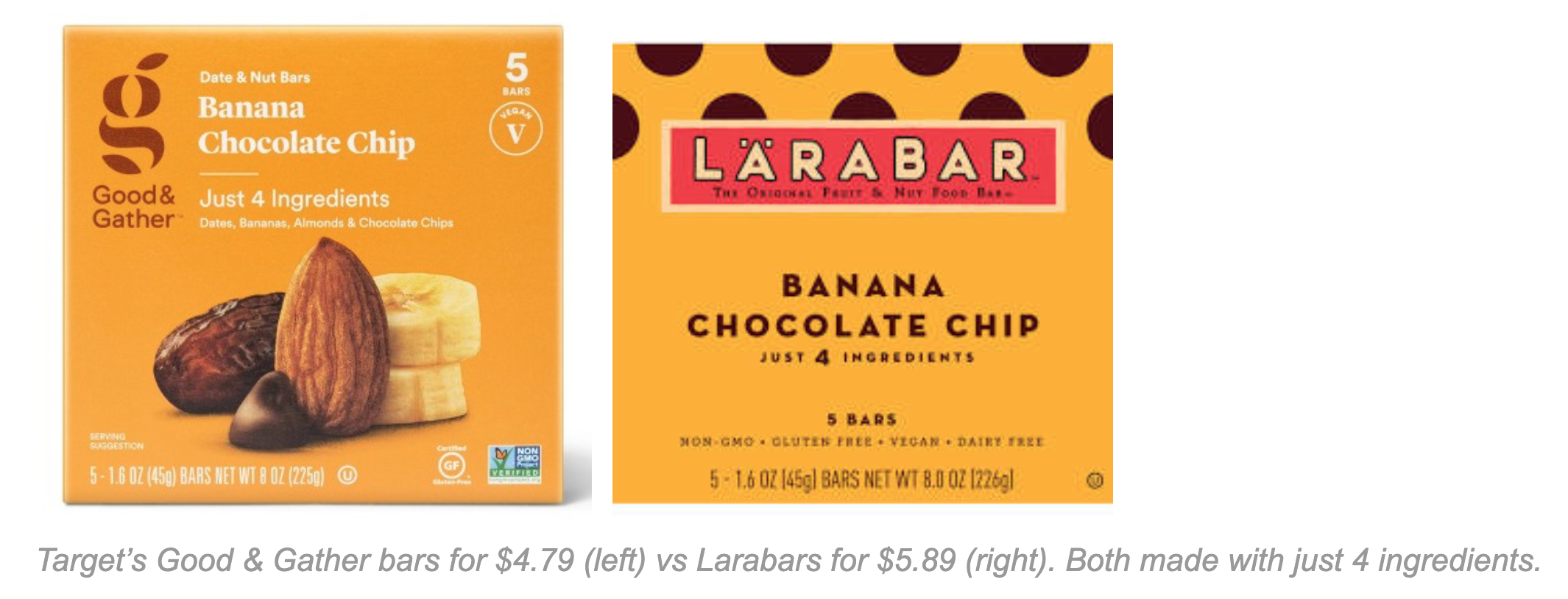

In particular, customer education around nutrition labels and preferences for cleaner, shorter ingredient lists can actually make it harder for new brands to compete.

If ingredient simplicity drives velocity, then of course retailers will chase a simpler ingredient list. This is, paradoxically, more challenging than a more complex ingredient list (full of preservatives and cheap chemicals), but achievable when expanding into the premium tier, which is exactly what Target is doing with Good & Gather.

And a retailer’s ability to buy raw ingredients in bulk at discount prices and sell directly to customers via private label means they’ll not only win on sourcing, but also pricing.

That pushes CPG brands in the opposite direction: product differentiation, not through simplicity, but through innovation.

What’s Left?

CPG innovation comes in a few forms: process innovation (Halo Top’s lower calorie air-whipping method), new ingredients (Oatly introducing oat milk), foodtech (Impossible Foods’ meatless meat). Unfortunately innovation is rarely defensible in food & beverage. It’s nearly impossible, especially for a small emerging brand, to own a supply chain or patent a manufacturing process (when they do, investors should definitely pay attention).

This is why, historically, emerging brands have best been able to compete via branding and marketing. Unfortunately, I’m just not sure that’s enough anymore.

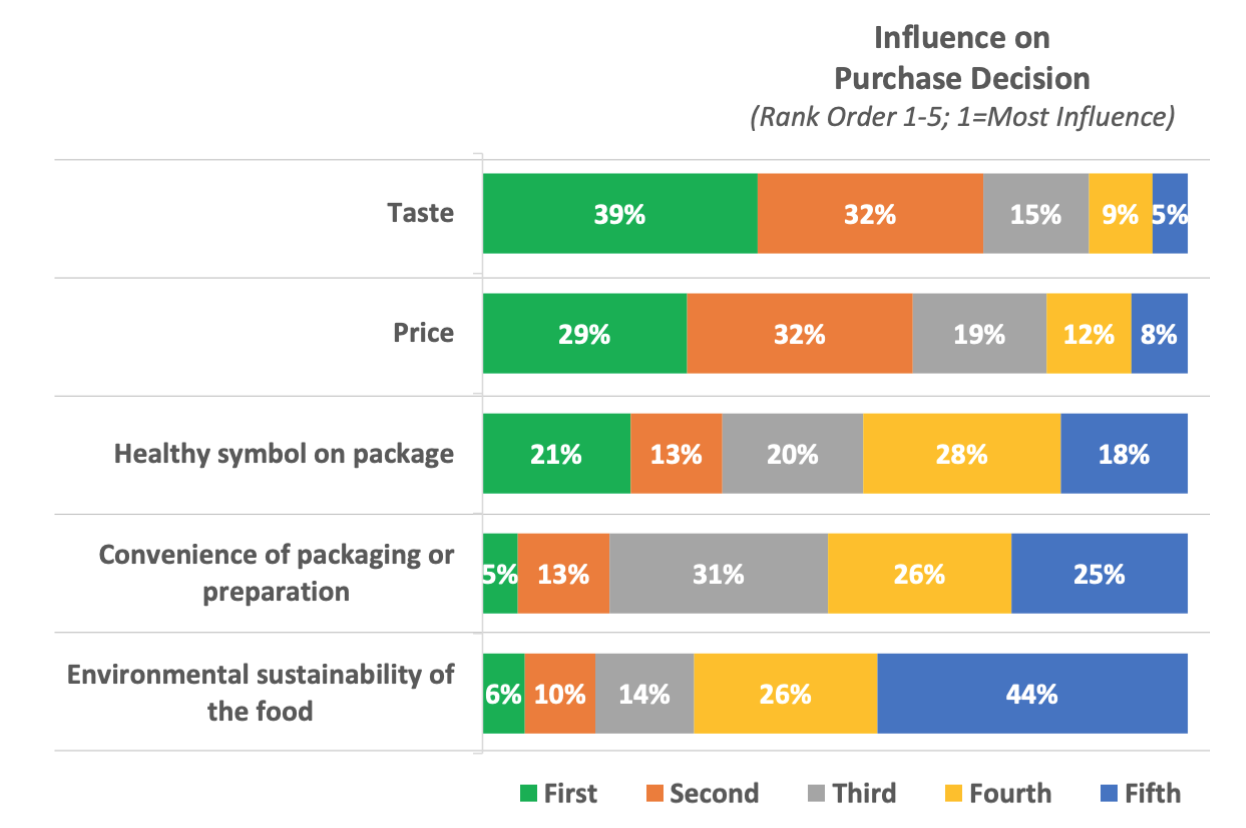

There is a silver lining. Taste continues to rank above all other purchasing decisions for food and beverage. And taste is a democratic value proposition, equally accessible to small startup brands as it is to retailers.

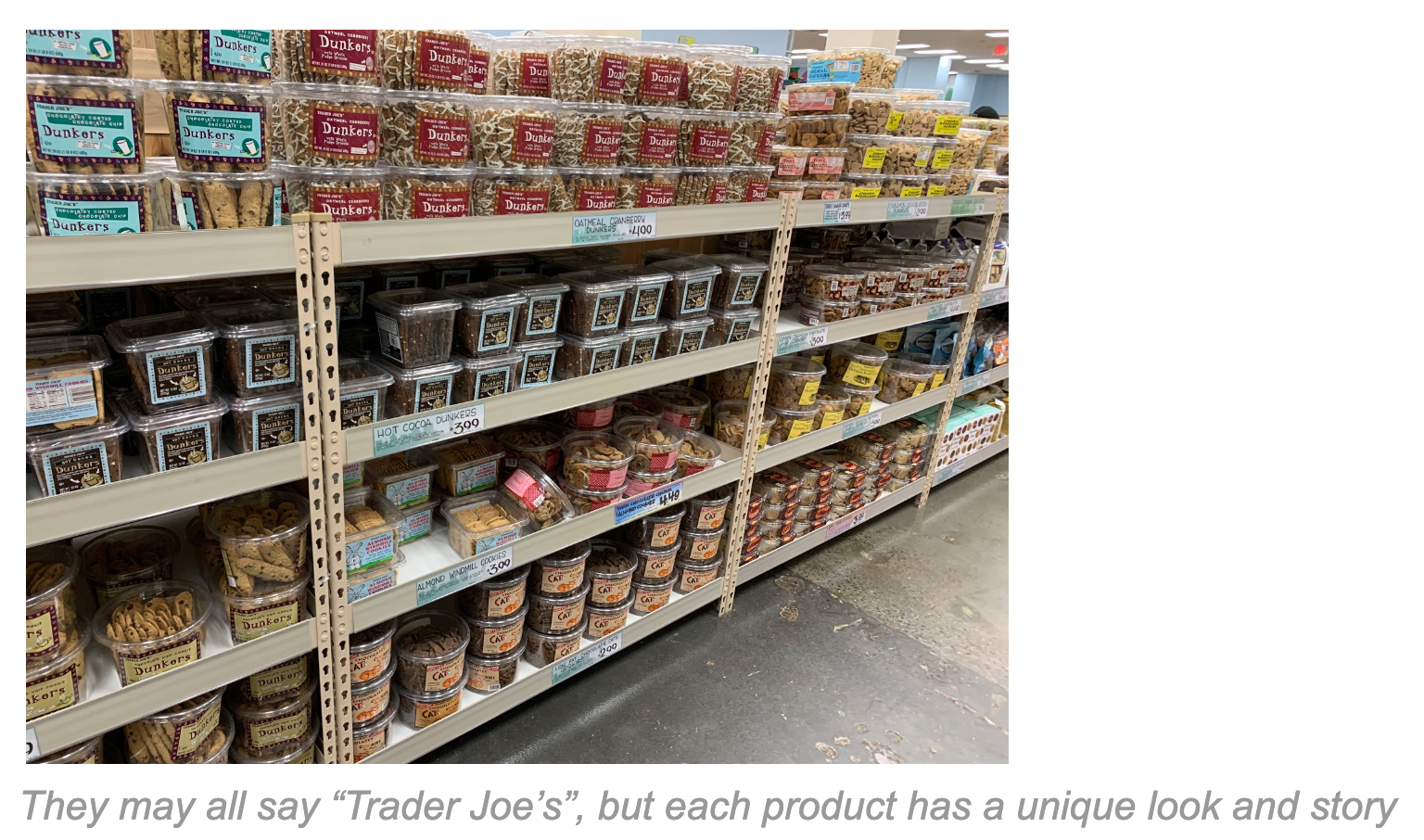

TJs is a unique case study and a lesson in branding unto itself. Over 90% of the products are private label. And although stores present a cohesive aesthetic, each product has a unique identity and podcast-worthy backstory that consumers can rally around. I often find myself cheerleading the wonders of EBTB and chocolate hummus to anyone who can stand to be around me for more than ten minutes.

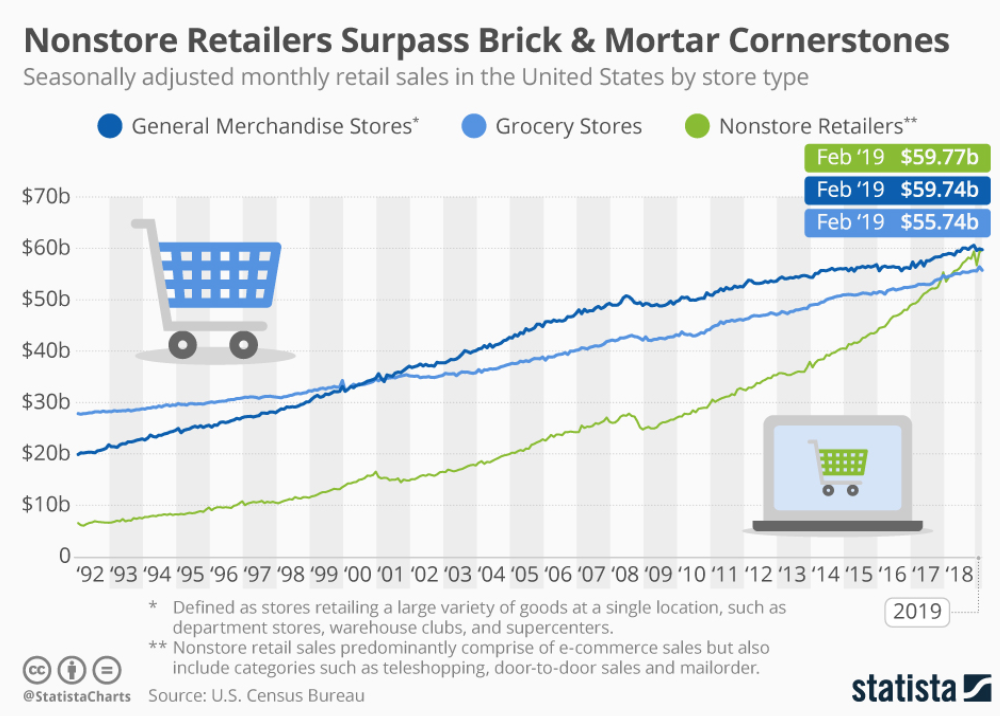

Target will likely never be Trader Joe’s, but we can forgive them for trying, given grocery stores and supermarkets face several existential threats of their own, as sales continue to slump.

So, is CPG doomed?

No, but I do think it has to change. Startups aren’t just competing against each other or incumbent name brands, but retailers who are highly incentivized to market their own products.

Of course, one solution is to sell directly to customers online and cut the retailer out of the equation. That’s the magic of brands like Magic Spoon. But this option is only accessible for select high margin, shelf-stable products. And, again, as social media becomes less effective it’s harder and harder to make this model work.

As evidenced by TJ, consumers still love product stories and will advocate for food and beverage items they’re passionate about, particularly the ones that taste really, really good. And while there are plenty of TJ brand loyalists, it’s hard to imagine Target can cultivate any fangirls for Good & Gather, so there’s still plenty of room for startups to compete.

If they focus on taste or independent storytelling, they might stand a chance.