Natural Maniacs

No one should be shocked when people who think about the world in unique ways you like also think about the world in unique ways you don’t like.

Let me try to explain Elon Musk’s recent behavior.

What kind of 32-year-old thinks they can take on GM, Ford, and NASA at the same time? A freakin’ maniac. The kind of person who thinks normal constraints don’t apply to them – not in an egotistical way, but in a genuine, believe-it-in-your-bones way. Which is also the kind of person who doesn’t worry about, say, Twitter etiquette.

A mindset that can dump a personal fortune into colonizing Mars is not the kind of mindset that worries about the downsides of hyperbole. And the kind of person who proposes making Mars habitable by constantly dropping nuclear bombs in its atmosphere is not the kind of person worried about overstepping the boundaries of reality.

People love the visionary genius side of Musk, but want it to come without the side that operates in his distorted I-don’t-care-about-your-customs version of reality. But I don’t think those two things can be separated. They’re the risk-reward tradeoffs of the same personality trait.

Same for Steve Jobs, who was both a genius and a monster of a boss.

Same for Walt Disney, whose ambitions pushed every company he touched to the razor’s edge of insolvency.

Same for the LTCM guys, who could accurately calculate everything except the limits of their intelligence.

Some people are natural maniacs, and you can’t ask for the maniac parts you like without realizing there are maniac parts that might backfire.

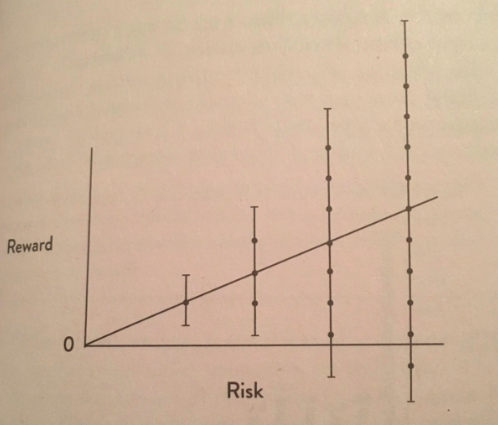

I love this chart, from Brian Portnoy’s new book. Risk and reward does not grow linearly – the bold bets come with some nasty warts. That’s as true for people as it is assets:

There is a thin line between bold and reckless, and you only know which is which with hindsight. And the reason there’s a difference between getting rich and staying rich is because the same traits needed to become rich, like swinging for the fences and optimism, are different from the traits needed to stay rich, like room for error and paranoia. Same thing with personalities and management styles.

“You gotta challenge all assumptions. If you don’t, what is doctrine on day one becomes dogma forever after,” John Boyd once said.

That’s the kind of philosophy you’ll be remembered for – for better or worse.