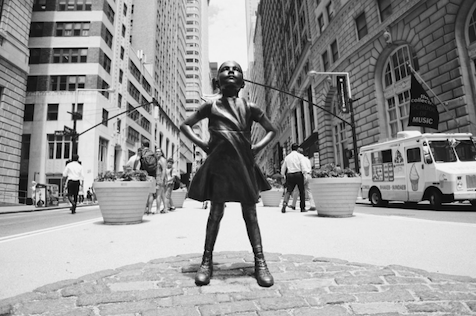

NYC: Looking To Its Past To Understand Its Future

“The true New Yorker secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding.” - John Updike

There has been a lot of recent talk about the impending death of New York City.

Some fear that if COVID-19 is here to stay, a densely populated city is the worst possible place to live. Others, including entrepreneur James Altucher, believe that by the time the virus fades, New York as we know it will have disappeared, too. Jerry Seinfeld happens to disagree—and I’m with him.

Altucher’s argument hinges on the idea that New York’s businesses, culture, restaurants, and colleges won’t come back because of one thing: bandwidth.

The prevalence of high-speed internet has made telecommuting, a popular work trend, possible for years. Now, COVID-19 has provided companies with the ultimate test case, changing our perception of productivity in remote workers and, in some instances, allowing businesses and residents to move out of New York’s pricy real estate market.

The idea of increased bandwidth killing cities is not new. In his 1980 book The Third Wave, futurist Alvin Toffler paints a picture of a post-industrialist society where armies of workers are freed from the inconvenience of urban life by computers and telecommuting.

But real life isn’t determined by futurist predictions.

To fully understand why New York won’t die anytime soon, I went back to its birth to remind myself how resilient it truly is.

New York City’s first big economic moment came in 1623 when, thanks to its geography, the Dutch West India Company identified it as the ideal outpost for a trading village. Along with central access to the eastern seaboard, New York has a deep harbor and is connected to the Atlantic Ocean, the Hudson and East rivers, and later, canals.

Naturally, New York City became the most important port in the 18th century and the largest city in the “New World.” As shipping evolved into a hub-and-spoke system, these advantages further cemented the city’s economic importance.

By the early 19th century, an entire, bustling economy launched around New York City. Shipping, followed by manufacturing, were the economic cornerstones of the time. When sugar came into a port, it made sense for its refineries to be located nearby. Cotton and other textile imports birthed the garment district, where those textiles were turned into clothes. When English novels arrived, the first pirate to print them would be rewarded with the market, which meant publishing houses needed to be close to the port, too. New York City’s geography was a competitive advantage.

Incredibly, this boom lasted all the way until the mid-20th century when globalization eventually neutralized the geographical advantages of the port city and labor abroad proved too mighty for the manufacturing economy.

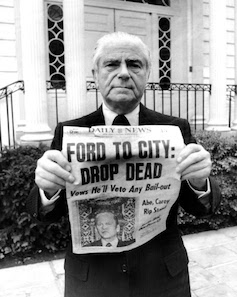

Then, things changed.

In just five years, from 1969 to 1974, New York City lost over 500,000 manufacturing jobs. By 1975 over one million households were dependent on welfare.

Still, this remains a nostalgic time for New Yorkers.

It was a cheaper city where creativity thrived (even Soho was affordable). While just leaving your apartment could be dangerous, it wasn’t uncommon to walk down the street and see artists like Andy Warhol or Jasper Johns on one block, and mobsters like John Gotti on the next. The Ramones, Blondie, and Talking Heads were regulars at CBGB on Bowery, while at the same time some local landlords burned their buildings to collect insurance money.

It was also a time of reinvention. Although much of the labor force moved out of the city, knowledge workers remained and continued to innovate. Seamstresses left; designers stayed and gave rise to New York’s fashion industry.

The business of publishing piracy deteriorated; publishers who stuck around spawned New York’s media industry. Shipping and manufacturing declined; their financiers remained and laid the groundwork for the modern-day financial services industry.

That brings us to today, where the financial services sector endures as the anchor tenant of the city’s economy, representing over 40% of its payroll.

While some might hate this idea, I think it’s true: as the finance industry goes, so goes NYC. With the strong economic backbone provided by the financial services industry, New York can and will continue to remake itself as needed to suit the times.

In the face of COVID-19, that change is all but certain. But not all change is bad—or even what it appears on the surface.

For example, much has been made about people fleeing the city and the suburban home sales boom. Yet there’s a greater truth behind those numbers: One million people have moved from the tri-state area (New York City included) over the last nine years. Why? Costly living expenses and high taxes are among the top reasons. Retail has experienced a similar setback. Rent has become so artificially high that as big-name brands moved in, they pushed the smaller businesses that make New York unique out. According to the New York City Comptroller’s Office, vacant retail space doubled in New York from 2007 to 2017.

As Duane Reades and Starbucks give up a few of their many storefronts and rent drops 10%, it leaves an opening that, with the right financial support, small and local businesses could fill again. There’s no denying that today New York is experiencing growing pains, but I see this as just another fitful period before progress.

Once this moment in history is over, I’m hopeful that the after-effects of COVID-19 could actually clear the way for diverse, creative businesses to flourish.

I’m hopeful that it opens the door for the city’s educated, entrepreneurial population to create new ideas, which will drive forward a new wave of economic growth, art and culture.

I’m hopeful that Zoom cannot reverse millions of years of human evolution that has made us experts on learning from the people next to us in real life.

I’m hopeful people will realize that cities are actually better places to live for our climate.

And, at the end of all of this, when we can all shake hands again, I’m hopeful that we’ll find that not only is New York not dead—it’s thriving.