The Ugly Scramble

A truth in one field often shines a light on another. So let me tell you a story about what cats falling out of buildings teaches us about businesses surviving Covid-19.

In 1988 two New York City veterinarians did a study on a topic they had unique insight into: What happens to cats that fell out of the city’s high-rise windows.

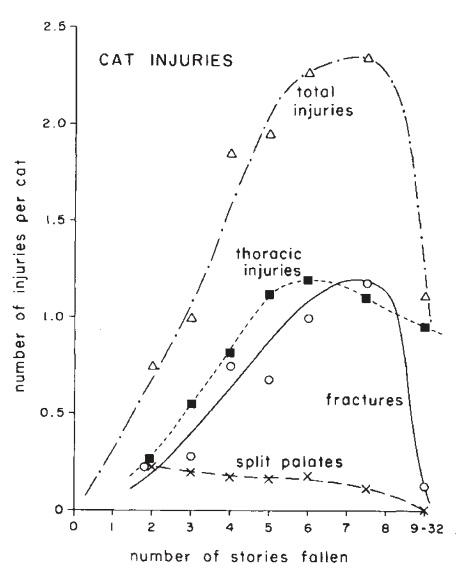

They found something counterintuitive: The relationship between the height of a cat’s fall and the injuries it suffers is an upside-down U.

A short fall is safer than a medium-height fall. But there’s a point where the further a cat falls, the less injury it’s likely to face.

It looks like this:

What’s happening here?

Potentially lots of things, including dumb luck and cats that didn’t make it to the vet.

But a mix of physics and psychology offers an explanation.

Cats have an amazing ability to right themselves during a fall, their bodies acting like gyroscopes to help them land on their feet.

The quirk is that a falling cat’s initial instinct is to extend its limbs straight down, locked into place. That’s the fastest way it can right itself, which is helpful during short falls. But at medium-height falls (4-7 stories) locked limbs are a liability, prone to snapping as they absorb the brunt of the impact.

Then something interesting happens after about seven stories.

Cats hit terminal velocity at about 60 miles per hour, which they’ll achieve after falling about 90 feet. That’s when acceleration stops and free fall begins. And just as accelerating from 0-60 mph in a car pushes you into your seat while driving at a constant 70 mph on a freeway doesn’t, things calm down for the cat once acceleration ends and terminal velocity is reached.

The relative calmness of terminal velocity loosens the cat’s locked limbs. As they relax “the vestibular system is no longer stimulated and the cat orients its limbs horizontally,” one study wrote.

That sets up a safer, gentler landing.

Jared Diamond explained in a 1988 article in Nature that the horizontal limbs come out “in flying-squirrel fashion, thus not only reducing the velocity of fall but also absorbing the impact over a greater area of its body.”

Risk isn’t always intuitive: Higher falls give cats time to prepare for a safer landing.

This has obvious limits. The final distribution might look more like an N than an inverted U, with super-high falls leading to the most injuries. (Please don’t test this at home).

But there’s an important observation:

Risk depends on how hasty your response must be. A small problem you have to scramble to protect yourself from with a snap judgement can be more dangerous than a larger problem you have time to deal with.

That’s as true for businesses as it is for our poor cats.

Every business will be impacted by Covid-19. Some worse than others. But one of the biggest differences in how much permanent damage 2020 will cause is whether a business has to scramble to protect itself or calmly deal with the new world.

Let me give you an example.

United Airlines wasn’t in good shape before Covid. Then the bottom fell out. It may be about to lay off half its staff, which is the kind of thing that’s hard to recover from even if demand returns. Workers will go find something else to do.

Southwest Airlines is in a different spot.

Long one of the most efficiently run airlines, its CEO told employees this month:

I want you all to know we will not furlough or layoff any Southwest employees on October 1 [when bailout funds expire], unlike our major competitors. Further, we have no intentions of seeking furloughs, layoffs, pay rate cuts, or benefits cuts through at least the end of this year.

He went on:

In January of this year, we had the lowest amount of debt to total capital in our history and a surplus of cash from 2019’s strong profits. We were prepared for the unexpected.

United is cutting 60% of its flight capacity later this year. Southwest is cutting 25%, its CEO noting that “we need be careful of making any major adjustments to the schedule. It could actually do more harm than good.”

United stock is down 64% year to date; Southwest, 36%.

Both airlines faced the same risk, the same virus, the same industry collapse. But United had to scramble towards a brutal fix while Southwest can breathe and think through a solution. It will likely make all the difference in the world.

Risk is weird like that.

There is no topic in business and investing that gets more attention than risk. But it’s almost always viewed through a universal lens: “What risks are we going to face in the future?” Or just simply, “What’s the economy going to do next?”

But risk has little to do with what’s going to happen next and a lot to do with how much you can endure, and how calmly you can react to, whatever happens next.

To the leveraged investor a small setback is a huge risk because of how they’re forced to deal with decline: by selling to cover their debts, right now, this moment, whatever the price is. Don’t think, just scramble to do what you gotta do in the face of panic. They’re like the cat locking its limbs into place, doing whatever they can to survive even if it breaks them to pieces.

To the patient investor with a ton of cash, a huge market decline requires no immediate action. And not because it doesn’t affect them – it often does – but because however it affects them can be dealt with slowly and methodically. Maybe they realize they want a more conservative allocation. They can come to that conclusion after thinking it through, hearing opposing views, weighing alternatives, and calmly executing at the right time. Doing so may lead them to a different choice than their initial gut reaction. Taking time to understand a complicated problem often does.

That’s the thing: The difference between snap reactions vs. taking your time to think is night and day.

Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow is a play on his idea that you have two types of thinking: System 1, which is fast and instinctual (cat locking its limbs out) and System 2, which is slow and deliberate (cat relaxing and pushing its limbs horizontally).

He writes:

System 2 is the only one that can follow rules, compare objects on several attributes, and make deliberate choices between options. The automatic System 1 does not have these capabilities. System 1 detects simple relations and excels at integrating information about one thing, but it does not deal with multiple distinct topics at once, nor is it adept at using purely statistical information.

Think about how complex the business and investing problems we face in 2020 are.

When will there be a vaccine?

How much will government stimulus change things?

Will consumer behavior be permanently altered?

Who wins the election?

What will governors do?

What will the Fed do?

What do all these things happening at the same time mean?

There are so many moving parts, so much nuance.

So much need to think slowly, wait for more data, and come up with a plan that isn’t a forced reaction to a single piece of news.

Some companies can. Some investors can.

But to me the most universal lesson of 2020 is the value of room for error.

Avoiding, as much as possible, the scramble of making snap decisions because you don’t have time to think through a problem with a deliberate long-term strategy.

Embracing, as much as possible, anything that gives you time, options, and flexibility.

Like a cat with nine lives.