Some good eggs

This interview is part of the inaugural issue of Featuring, a newsletter celebrating creative entrepreneurship. Read more and sign up here.

When Rob Spiro set out to build Good Eggs, he didn’t have a product, a business plan, or even a half-baked idea—just a mission: to grow and sustain local food systems worldwide.

With one acquired startup under his belt, Spiro now wanted to harness the power in Silicon Valley for good. Having worked on a farm following college, Spiro remembered the effect that local food movement had on the land and community. He wanted to share that with others by helping farms and local businesses compete and make local goods more accessible to consumers.

Spiro’s mission-first approach was a success, quickly attracting the right people and creating a framework for Good Eggs to thrive. Founded in 2011, Good Eggs now serves four cities1 in the U.S. and continues to grow, delivering local goods and produce to people across the country.

We spoke with the founder and CEO on what it takes to balance good vibes with good eggs and ultimately making the world a better place.

That mission statement really resonated with early investors like Collaborative Fund. How has that vision evolved since then?

The good news is, is if you do a good job of articulating your mission, then you’re going to attract the right people. The first month was spent coming up with that mission statement. We had no idea what we were going to do with it. It wasn’t a product idea, it wasn’t a business idea, it was a social and environmental goal around which we built the company.

We didn’t realize going into this all that we were going to build a warehousing business, especially as technology entrepreneurs. We spent around a year and a half spending time with farms and ranches, testing ideas and apps that we built, throwing them away when they didn’t work, and learning as much as we could. Over time, our apps and prototypes became better and more robust, involving not just technology, but warehouses and other services.

As we kept learning, we realized that what local food systems actually needed was what allowed companies like Walmarts, Whole Foods, and Krogers to thrive—a distribution infrastructure. These companies have massive centralized warehouses that serve multiple states. If you’re a small farmer and you want to sell direct, there’s no alternative. Either you’re driving to a local farmers market or you’re doing your own home deliveries. We filled that need by building central warehouses, which we call ‘food hubs,’ and hiring teams to carry out home deliveries.

How has technology impacted the way you do business?

Technology is really powerful for a number of reasons. There’s the impact it has on the way we consume food and the way we purchase anything is entirely different now than 20 years ago. There’s an opportunity to take advantage of the new way people buy things—to get them to buy the better thing, better for them and better for the world. The biggest way we use technology is inside our food hubs. The way that we’re building them is so different than the way they could have been built ten or even five years ago due to custom tablet applications that power each step of the process. It means that we can provide a service that couldn’t have been possible before.

In order to have a different kind of distribution infrastructure for these local products to reach market, you need to build really lightweight, small-scale distribution and have it proliferate. Grocery stores build heavyweight, large-scale infrastructures because it allows them to apply economies of scale. The only way to for us to compete is by being extremely technology-driven.

How did you choose what cities to expand to first?

We started in San Francisco, but realized that the decisions we were making might only work there and we wanted to build something that could work anywhere. We weren’t ready to scale, but needed more inputs, so we decided to expand to a few select cities.

We wanted at least one city that was smaller and low income, one with really bad traffic, one that has really dense apartment buildings, one with a really bad winter—because so much of our goods are seasonal produce and fruits. We pieced together this set of four—San Francisco, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Brooklyn—and we’ve been running with them ever since.

With Good Eggs, you’re selling so much more than fresh produce. How do you market that?

We try to get out of the way and let the food tell the story. The message really comes across with the food more than anything else. We have over a thousand producers we work with across these four cities. Farmers, bakers, chefs, fishermen, and lots of amazing small businesses are producing food that tastes so much better than what you can get at the supermarket. We’re excited to be a platform for those folks to share their craft.

How do you see the food supply system evolving?

I hope that these local systems continue to grow and that, as a result, it puts pressure on the industrial food system, as well. Recently, McDonalds committed to not use antibiotics used on humans in their chickens—which is crazy—but a great move forward. When a company like McDonalds makes a decision like that, it has a huge impact on the environment. If local food systems continue to grow, they will put pressure on other companies to change how they do businesses.

What do you see as the difference in impact of a for-profit venture versus a non-profit?

There are lots of ways to try to solve problems. When I think about for-profit business and the capital markets that fuel them, I think see it as an enormous engine that can be attached to any kind of vehicle.

You have this huge engine that is normally applied to a very certain kind of vehicle, like a jet, but the engine itself, like for-profit business driven by capital markets, doesn’t necessarily lend itself better to one type of project. It doesn’t have its own morality or immorality to it. It’s amoral, so there’s every reason why you should take this engine of a for-profit business and put it toward changing the world in a positive way.

What’s exciting to us about Good Eggs is that there really is full alignment between building a business and doing good in the world. Good Eggs is intended to grow local food systems, doing two things at the same time. One, it generates a good business and, two, it provides a platform for small businesses that are taking care of the land, taking care of the customers, providing healthier food. We’re trying to align all of those things. We certainly believe it’s possible and wish more people did it.

What advice would you give to companies trying to balance the two?

Make your ideals extremely explicit. In order to have the most alignment between your employees and your management and your investors and your customers, you need to say specifically why you’re doing what you’re doing and how you’re going to balance that. Explain the way in which you’re going to ensure that you will build a profitable business, while at the same time achieving this do-good mission.

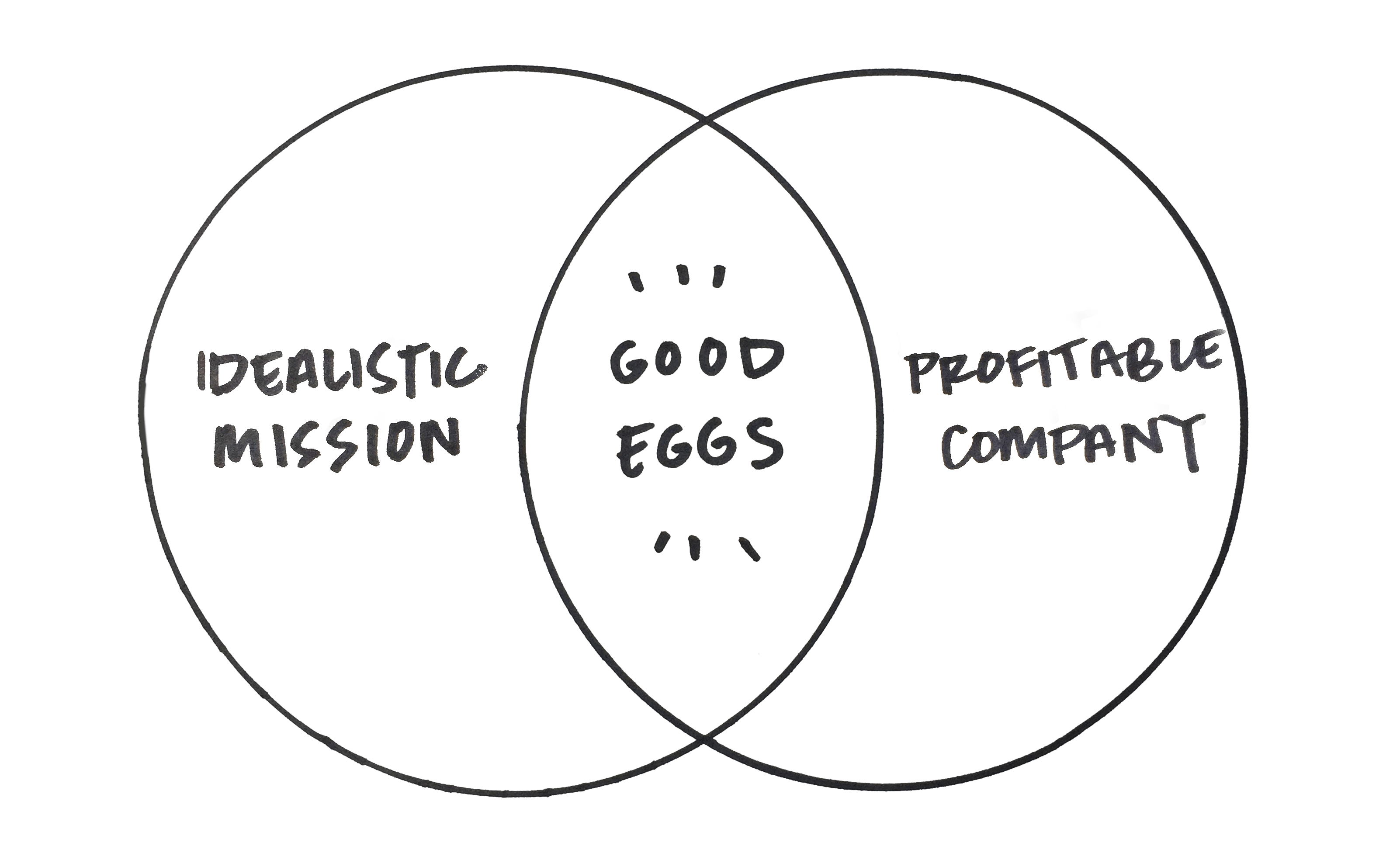

We talk a lot about profits and idealism. Here at Good Eggs, we have a Venn diagram we draw on the wall that reads ‘idealistic mission’ and ‘profitable company.’ The middle is Good Eggs.

We have a rule that we try to do both and never compromise, which means that we never make a decision that fits one, but not the other. We recognize that that makes our job harder, but even so, that’s what we’re going to do because that’s why Good Eggs exists.

This interview is part of Featuring, a newsletter celebrating creative entrepreneurship produced in collaboration with i am OTHER. This month’s theme was ‘Do Good.’ Read more and sign up here.