The Big Lessons of the Last Year

History is one damned thing after another. A war ends, a boom follows, then a crash, then an uprising, then a pandemic, a breakthrough, a new boom, a new war. On and on, from agony to awe.

A question that always arises after a terrible event is why haven’t we learned our lesson?

Financial crises keep happening, again and again. People have been making the same investing mistakes for hundreds of years. The same military blunders, over and over. The characters change but the plot rarely does.

Jason Zweig explained years ago that part of the reason the same mistakes repeat isn’t because people don’t learn their lesson; it’s because people “are too good at learning lessons, and they learn overprecise lessons.”

A good lesson from the dot-com bust was the perils of overconfidence. But the lesson most people took away was “the stock market becomes overvalued when it trades at a P/E ratio over 30.” It was hyperspecific, so many of the same investors who lost their shirts in 2002 got up and walked straight into the housing bubble, where they lost again.

The most important lessons from a big event are usually the broad, 30,000-foot takeaways. They’re more likely to apply to the next iteration of crisis.

Covid-19 is far from over, but we’re now more than a year into this tragic mess. Enough has happened that we can start to ask “what lessons have we learned?” If you’re a doctor or a health regulator, some of those lessons are hyperspecific. But for most of us the biggest lessons are broad.

A few that stick out:

1. Big risks are easy to underestimate because they come from small risks that multiply.

If asked, “What are the odds that a group of scraggly young men can inflict massive damage on the strongest and most militarized nation in the world?” you might reasonably reply “extremely low.” Maybe even zero.

But if asked, “What are the odds a group of scraggly young man can be radicalized by a charismatic maniac (extremely high), sneak box-cutter knives through airport security (not hard), use those knives to kill pilots (easy), commandeer a plane (reasonably easy) and crash it into a building (inevitable at this point), your answer might be, “How could we not have seen this coming?”

Big risks are easy to overlook because they’re just a chain reaction of small events, each of which is easy to shrug off. A bunch of mundane things happen at the right time, in the right order, and multiply into an event that might look impossible if you only view the final outcome in isolation. Math is hard, but exponential math is deceiving.

Covid is the same.

A virus shutting down the global economy and killing millions of people seemed remote enough for most people to never contemplate. Before a year ago it sounded like the one-in-billions freak accident only seen in movies.

But break the last year into smaller pieces.

A virus transferred from animal to human (has happened forever) and those humans interacted with other people (of course). It was a mystery for a while (understandable) and bad news was likely suppressed (political incentives, don’t yell fire in a theater). Other countries thought it would be contained (exceptionalism, standard denial) and didn’t act fast enough (bureaucracy, lack of leadership). We weren’t prepared (common over-optimism) and the reaction to masks and lockdowns became heated (of course) so as to become sporadic (diversity, same as ever). Feelings turned tribal (standard during an election year) and a rush to move on led to premature reopenings (standard denial, the inevitability of different people experiencing different realities).

Each of those events on their own seems obvious, even common. But when you multiply them together you get something surprising, even unprecedented.

Big risks are always like that, which makes them too easy to underestimate. How starkly we have been reminded over the last year.

2. A lot of undue pessimism comes from underestimating how quickly and firmly people adapt.

Real GDP per capita has increased 9.3x since 1900.

Imagine it’s 1900 and a time-traveler from 2021 says, “Great news everyone. Your great-grandkids will on average be 9.3 times wealthier than you are today.”

They would be ecstatic – that kind of wealth must have seemed unimaginable. They’d assume their great-grandkids will be walking balls of ecstasy, waking up every morning astounded at how rich they are.

Which, of course, describes virtually no one in 2021.

People are astoundingly good at adapting. When contemplating change it’s tempting to draw a straight line and assume a change in circumstances leads to an equal change in how you feel. But it’s never like that. When faced with a change people quickly say, “OK, this is the new baseline. Our expectations now begin there.” It’s part of why we are so bad at forecasting.

And the same thing can happen in reverse.

If you went back to last January and said, “What does the world look like if no one can go to the office, face-to-face interaction is gone, every school is closed, half the world is on sporadic lockdown with people banned from leaving their home, and it stays like that for a full year?”

I think you would have said, “My god, that’s the end of the world. This will be 10 times worse than the Great Depression.”

Which – without minimizing how many jobs have been lost and businesses have closed – it has not been, on whole. Or anything close. And I’m not just talking about the stock market: Incomes are at an all-time high.

It is too easy to assume that when faced with terrible circumstances people will only muster a normal response. But it’s never like that. Expectations reset, survival instincts unleash new creative juices, and people start thinking and acting in ways they wouldn’t have contemplated before the crisis.

Part of the reason global supply chains are broken right now is because one year ago manufacturers reasonably took stock of the world and said, “well, there goes everything.” Production was scrapped. But demand came back faster than nearly anyone imagined.

A lot of that demand came from stimulus, but here we find the same point: Six trillion dollars in stimulus would have seemed unfathomable 13 months ago, but faced with a proper disaster it passed through without much fuss. Policymakers adapt what they’re willing to do; voters adapt what they expect.

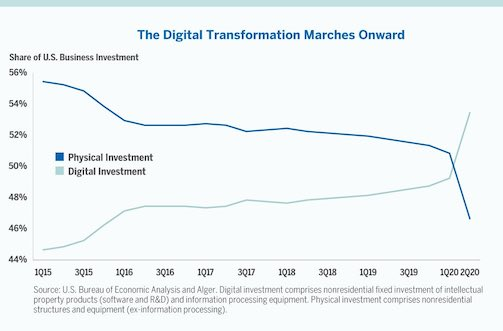

Businesses adapt their own way. It’s astounding: 2020 became what people in the early 1990s assumed the world would look like in 2000:

Virtually every business operates in a new world today – a world that was hard to even imagine a year ago.

Hard to even imagine is the key point. So many restaurants have closed in the last year, but more assumed they would have to close a year ago but managed to survive by selling takeout, which wouldn’t have even seemed like an option before because there wasn’t enough consumer demand for takeout until Covid hit.

The history of pessimism is as long as the history of progress, and I think part of the reason why is that it’s so easy to overlook how people adapt to adversity.

3. History is only interesting because nothing is inevitable.

Carl Richards says “Risk is what’s left when you think you’ve thought of everything.”

I’ve found no better definition.

The finance industry spent a decade debating what the biggest risk to the economy was. Was it tax hikes? Money printing? Budget deficits? Trade wars? Setting interest rates at 0.5% when the proper rate should have been 0.75%?

And of course the answer was none of those. It was a virus.

That’s usually how it works. Look at virtually any decade and you’ll see that the most important news story was something no one was talking about until the moment it occurred.

If something is in the news, people are thinking about it. If they’re thinking about it they’re at least partially prepared for it. And if they’re prepared for it its damage is mitigated when it arrives. It’s the surprising stuff that really moves the needle and becomes one of the few events you can look back at and say, “that was all that mattered.” Pearl Harbor, September 11th, Covid-19. The most important common denominator of those events isn’t that they were big; it’s that they were surprises.

Whatever your view of the world was a year ago, it’s different now. Maybe Covid’s biggest lesson is accepting how true that will be going forward, too.

Daniel Kahneman says that when you experience a surprise the correct takeaway is not to assume that event will happen again; it’s to accept that the world is surprising. The big lesson is to realize that you will again be hit by things you didn’t see coming, that no one was talking about, and that will move the needle more than all the things you expected to happen combined.

Just one damned thing after another.