The Making of a Brand

An amazing thing about life before 1850 is that most people never experienced a world more than a few dozen miles outside of their birthplace.

Life was local. You ate food grown in your town. Your house was made of local lumber. Your clothes woven by a local seamstress. Bulk commodities were traded far and wide. But finished goods were a local affair. You knew the person who made them. That person was often yourself.

The industrial revolution and the Civil War changed everything. Millions of people were suddenly on the move. Railroads transferred goods farther and faster than ever before.

Robert Gordon writes in his book The Rise and Fall of American Growth:

As America became more urban and as real incomes rose, the share of food and clothing produced at home declined sharply. New types of processed food were invented … Many American men had their first experience of canned food as Union soldiers during the Civil War.

This was one of the biggest breakthroughs in history. But it posed a problem.

For the first time, consumers were disconnected from the production of their stuff. For most of history, a bad product was either your own fault, or could be taken up face-to-face with a local merchant. But canned food was batched together by dozens of regional suppliers, none of whom customers knew or could even identify. Without accountability, quality was horrendous. Harper’s Weekly wrote in 1869: “The city people are in constant danger of buying unwholesome [canned meat]; the dealers are unscrupulous, and the public uneducated.” No one knew who to trust.

The William Underwood Company solved this problem.

Starting as a pickle company in the 1820s, Underwood pioneered glass packing and canning. As the Civil War broke out, it supplied demand for canned meats, perfecting a meat spread it called Deviled Ham. People loved Deviled Ham. But the disparate production of canned meat gave the whole industry a reputation for inconsistency – sometimes rotten, sometimes watery, no two cans alike.

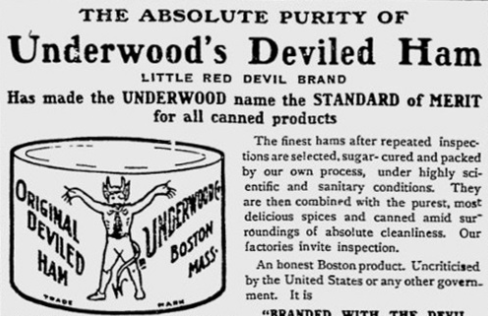

Underwood fixed this by creating a flaming red devil logo consumers could recognize. It added a tagline: “Branded with the devil, but fit for gods.”

The logo recreated the familiarity that face-to-face commerce provided for most of history. No matter what part of the country they were in, consumers who saw the devil logo knew they were getting a specific product made by a specific company under specific quality standards. Consumers came to associate the devil logo with something they previously had none of: consistency.

In 1867 Underwood took the logo to Washington and filed the first federal trademark.

It was the first brand.

The 1906 version of Underwood’s Deviled Ham

The idea of a brand spread quickly.

Kerosene took off in the late 1800s, but, like food, was inconsistent. “Good kerosene gives a light which leaves little to be desired,” wrote American Woman’s Home or Principles of Domestic Science in 1869. But it warned that impure kerosene was all too common, and could explode when lit.

John D. Rockefeller tackled this problem. He named his company Standard Oil because he wanted customers to know that one can of his kerosene would be no different from the next.

Companies caught on. “A mere 120 trademarks existed in 1870,” writes Gordon, “as compared to more than 10,000 registered in the year 1906 alone.”

Brent Beshore, CEO of private equity firm Adventur.es, was recently asked what a brand is. He replied:

Brand is the distribution of likely outcomes that you can expect from any company or person.

This meshes with the forces that created the first brands. Underwood and Standard Oil were not known as the best products in the market, although both were pretty good. But they built powerful brands because consumers knew exactly what to expect from them. The distribution of likely outcomes was small. Brand wasn’t about having the highest quality. It wasn’t even about building trust. “You don’t trust the Coca-Cola brand,” Beshore said. “You know what to expect from them.”

Knowing what to expect. That’s the essence of a brand.

Branding is more powerful than ever today, because consumer options have proliferated. There used to be three news channels. Now there are millions of blogs. The grocery store used to stock five types of toothpaste. Now Amazon offers 87,268.

Staying relevant in this world requires building a strong brand. But we often mistake brand for two of its cousins: marketing and design. The most important thing about a brand is that you can’t create one. You can create a marketing campaign. You can create a slick design. Both are tremendously important. But brand has to be earned through repetition, convincing people that what they experienced yesterday is what they can expect to experience tomorrow. It’s hard, and it can take a long time. But it’s sensationally powerful.

When you realize how much of a brand is just a tight distribution of outcomes, you see that powerful brands can be built on top of subpar products. Julia Child once asked her host to take her to the local McDonald’s. The host was horrified. Child explained: “I like McDonald’s. It’s always consistent.” Motel 6 is a powerful brand. You know exactly what you’ll get: A pitifully no-frills room, identical in every city. Same with Domino’s. It is not the best pizza in the world. But it’s pretty good every time, from Baltimore to Tokyo. That’s enough to make it the best-selling pizza in the world.

The big insight on brands is that consumers hate surprises more than they enjoy the chance at perfection. Truly amazing companies combine perfection with consistency. Apple is a good example. But it is an exception, and consistency still drives the bulk of its brand. Motorola and Blackberry made some amazing phones. But they sold them in a lineup that included some awful phones. The distribution of outcomes widened. The brands diminished.

Coca-Cola learned this the hard way. Its infamous 1985 New Coke formula backfired and caused customers to revolt, leading Coke to bring back its original formula three months later. The crazy part is that Coke conducted more than 200,000 taste tests, which overwhelmingly showed that people liked the taste of New Coke better than the original formula. The problem was, blind taste tests didn’t replicate the psychology buyers experience when buying soda in the store. In the real world, people didn’t care that New Coke tasted better. It didn’t taste like Coke. Which is what they expected.

Someone offered me career advice years ago: “If you want to strike it big as a writer, find one big trend and just keep hammering away at it.”

I don’t know if I followed it. Or whether I should have. But it’s not bad advice. Some of the biggest “brands” in writing aren’t the smartest or the best, but the most consistent. Sean Hannity and Rachel Maddow don’t offer the peak of insightfulness, but their viewers know exactly what they’ll get when they sit down to watch each night. Jason Zweig of the Wall Street Journal – who does offer some of the most insightful finance commentary – once wrote:

My job is to write the exact same thing between 50 and 100 times a year in such a way that neither my editors nor my readers will ever think I am repeating myself.

Here, too, consistently. As a reader, I know Jason will never stray too far from the bedrock principles of financial advice he has espoused over the decades. Coming back to his work each week feels less risky to me than reading a columnist whose views bounce all over the map. That’s why I, and hundreds of thousands of others, keep coming back. He’s built a brand.

History is full of parallels. Sometimes I wonder what the modern equivalent of Underwood’s Deviled Ham is. What’s the new frontier of making your product known that we’ll look back on 150 years from now as shockingly obvious?

Perhaps we’ll recognize that the pursuit of two things – speed and scale – tainted many brands. Maybe we’ll realize that slowing down to focus on quality and consistency is the new way to win over more customers.

The biggest branding challenge 150 years ago was signaling to customers that you could promise consistency – selling in. Today the biggest challenge is keeping that promise in a market where it’s easy to grow big quickly by sacrificing consistency – selling out.

Quality falling with quantity is visible in almost every industry. Health care satisfaction falling as hospital networks combine. Banks losing focus as they merged into behemoths. Blogs posting garbage as they seek clicks and volume. It seems to have picked up over the last decade, as technology makes scaling easier than ever.

Maybe we’ll look back and realize that the best way to grow big is to have a powerful brand, and the best way to build a powerful brand is to be good all the time rather than great some of the time.