The Many Challenges of CPG and Retail Startups

There are a lot of reasons to be excited about CPG and retail startups right now.

Legacy brands are poorly positioned to keep up with shifting consumer trends, so smaller startups are gaining market share by creating simple, natural, and socially conscious products with an authentic brand story. Consequently, as growth accelerates and M&A activity heats up, an influx of new capital is facilitating big innovations like lab-grown leather and vertical farming.

But companies that produce consumer goods like food and clothing face inherent challenges, many of which are being exacerbated by current trends, from shifting capital sources to increasing competition.

Here are just a few of the many road bumps on the path to consumer startup success:

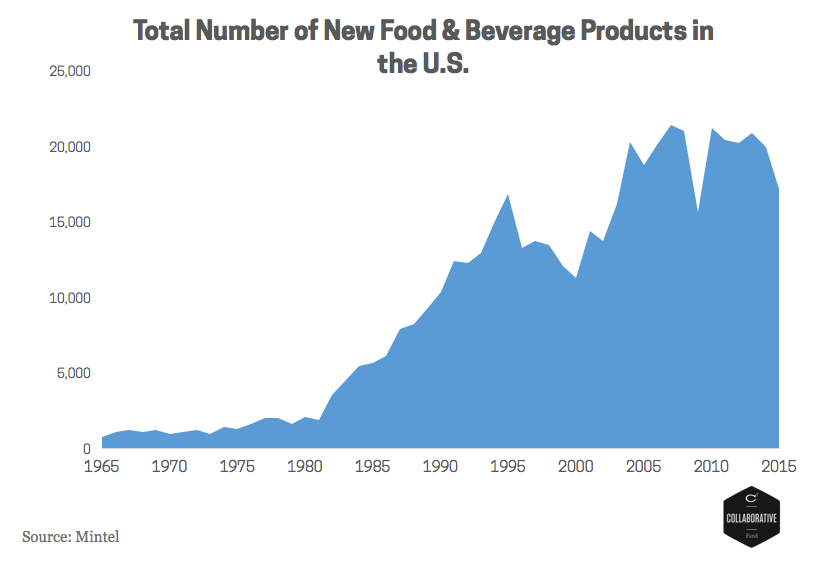

Too much competition for shelf space

E-commerce may be on the rise, but online orders still represent just 1% of food and beverage sales. This means that most customers are buying food and beverage products at grocery stores with limited shelf space. As new product introductions have accelerated, that shelf space has remained mostly static, leading to fierce competition. So brands have to produce results – and produce them fast – in order to retain coveted real estate at retailers like Whole Foods and Safeway. These companies don’t publicize product churn rates, but it’s estimated that approximately 85% of new brands don’t survive past two years.

Retailers are creating their own brands

It’s not just new brands that are competing with each other: retailers themselves are infiltrating the market. As companies like Warby Parker and ALOHA have validated the benefits of vertical integration – mostly notably, building direct relationships with customers at higher margins – traditional wholesalers like grocery and department stores are starting to push their own brands over third party labels. After a few disappointing quarters, Whole Foods doubled down on its lower-priced supermarket chain, 365 by Whole Foods Market, which is primarily stocked with its own in-house products in a similar model to Trader Joe’s. It’s still early days, but this trend could leave many startups, particularly food and beverage products that don’t sell well online, without a natural home for distribution.

Direct-to-consumer expenses are front-loaded

Though great for margins and long-term profitability, selling directly to consumers can be extremely expensive early on. There’s a reason companies like Bloomingdales, Target, and Safeway have acted as middlemen between brands and consumers in the past: it’s an inexpensive way for startups to gain exposure and leverage the marketing and distribution resources of more established companies. Vertically integrating from production to point-of-sale can be more profitable in the long-run, but expenses are more front-loaded as companies need to pay for those marketing and distribution costs all on their own from the very beginning. In particular, DTC startups often struggle to find early adopters without spending large amounts of capital on marketing.

Advertising on social media is getting more expensive

And, unfortunately, those marketing costs have only been going up. Social media is typically the preferred marketing strategy for early-stage consumer startups, as costs are lower than traditional print and television advertising and the direct connection to customers is very attractive for brand building.

But as more companies have adopted social media strategies, costs have been increasing. According to Business Insider, popular social media “influencers” who made around $100,000 in 2015 can now make that much for a single Instagram photo or blog post. Even though 81% of marketers say that social media ads are effective, those costs are getting harder and harder to justify. Social media is still a great way to communicate directly with customers, but generic, transparent ads are no longer sufficient: companies have to create meaningful brand stories in order to stand out.

Valuations are too high

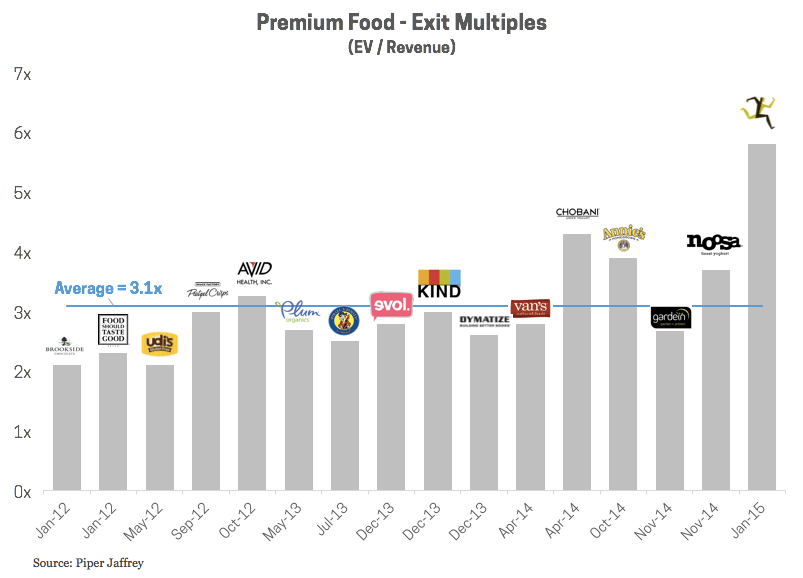

As the market heats up and growth accelerates, valuations for consumer startups have been creeping higher and higher. A handful of high-profile, high-multiple exits, like the acquisitions of Epic Bars and Krave Jerky for multiples over 5x, have exaggerated this effect, prompting even early-stage startups to seek valuations many times their revenues.

But the Epic and Krave acquisitions were outliers. Even exit multiples for premium food brands have averaged only 3.3x over the past five years. And early-stage consumer companies should not base valuations on exit multiples, but on comparable company metrics, which are typically closer to one to four times trailing 12 month net revenue. This early valuation gap is a problem for both investors and entrepreneurs, as it can lead to drawn out fundraises and disappointed investors in later stages.

VCs are changing the fundamentals

In the past, CPG or retail startups would plug along with limited capital for at least a decade before reaching the critical $10-15M revenue mark, at which point they’d catch the attention of private equity funds. Not exactly a recipe for big leap innovations. As venture capitalists have begun injecting more early-stage capital into the process, innovation has accelerated so that startups are better positioned to compete against big brands.

But this new type of capital is also shifting fundamentals. CPG and retail startups are seeking financing before achieving reliable revenues, producing solid margins, finding viable paths to long-term profitability, or even proving some level of product-market-fit.

And growth expectations are becoming more unrealistic as consumer startups are held to the standards of more traditional VC tech investments. While CPG and retail startups are growing faster than ever thanks to manufacturing and distribution efficiencies as well as improved social media-driven networking effects, growth paths for physical goods are still naturally slower than highly scalable software products. Rapid growth expectations can often lead companies to cut corners and compromise on quality in order to meet unrealistic investor demands.

Conclusion

This is just a taste of the many issues consumer products entrepreneurs need to navigate. I haven’t even mentioned high inventory down payments, sensitivities to commodity prices, FDA regulations, or shelf lives.

So while consumer products are getting more innovative, growth is accelerating, and acquisition opportunities are increasing, don’t underestimate the many challenges that come with launching a CPG or retail startup. Like founding any company, it’s certainly a lot harder than it looks.