The Thrill of Uncertainty

By the end of the study, pigeons were pecking a food lever up to five times per second “for as long as fifteen hours without pausing longer than fifteen or twenty seconds during the whole period.”

B.F. Skinner made a pigeon lose its mind.

Skinner, a Harvard psychologist, studied the science of incentives. He did this by giving thousands of animals different incentives to be rewarded with food. Sometimes the animal just had to hit a lever, and a food pellet popped out every time. Sometimes it had to learn a pattern – two lever taps, or a long tap, or a tap and a delay and another tap. Pigeons and rats are remarkably good at figuring this stuff out.

Part of Skinner’s research was determining what incentives are so powerful that they can’t be ignored, causing animals to become obsessed beyond the need for food pellets. What kind of incentives make a pigeon lose its mind?

He basically found three types of incentives:

Fixed. One tap gives one food pellet. Same result every time. Animals figure this out quickly but don’t get excited about it. “This is how I get food. OK. Move on.”

Changing. Today you get food with one tap. Tomorrow it will take two taps. The next day, a tap pattern. This gets animals excited. It’s a stimulative puzzle. “Oh! Let’s figure out how to get food today!”

Variable interval. Tap the lever and you will get food on average every hour, but that might mean five pellets in the next hour and then nothing for the next five hours. Animals will get the same amount of food over the course of a day, but at random and unpredictable times. This turns them into addicts. They lose their minds. “I know food will come so I’m going to keep tapping but AHHHH MAN WHEN IS IT COMING THE SUSPENSE IS KILLING ME JUST KEEP HITTING THE DAMN LEVER.”

The science behind this is how much dopamine you get for different rewards.

Fixed rewards are too easy to get excited about. Changing rewards offer enough buzz to want to figure out tomorrow’s puzzle. Variable interval rewards flood your brain with dopamine because that high is evolutionarily necessary to survive the hellish world of hunting and famine. The dopamine rush of obtaining something important that you knew would eventually come but didn’t know when is what keeps you hunting for more. The pigeons in Skinner’s study got so much buzz from variable interval feedings that they became compulsive, completely out of control.

“You can move from the pigeon to the human case,” Skinner once said. “[Variable interval] is at the heart of all gambling devices. It has the same effect. A pigeon can become a pathological gambler just as a person can.”

Variable interval rewards are why we compulsively check email. Some messages are really important, but you don’t know when the important ones will come, so you keep checking and checking.

Same with checking Twitter and Facebook.

Or watching cable news.

Or waiting for a boring meeting to end.

Find something that captures people’s attention and turns them into crazed animals and you will likely find a variable interval reward.

Now let’s talk about investing.

*****

U.S. stocks returned 7.5% a year over the last century. That means you doubled your money every ten years, on average.

But averages rarely happen.

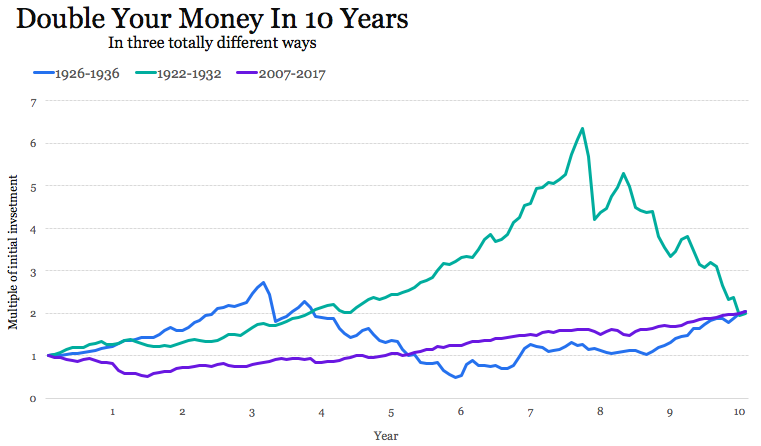

There have only been three times in the last century when stocks almost exactly doubled in a decade. Returns were nearly identical during these three periods, down to the basis point. But the path and emotions that got you there couldn’t be more different:

Go ahead and assume the market doubles every decade on average. But sometimes it goes nowhere for 20 years. Sometimes it goes up six-fold in a decade. The market rarely doubles every decade, and when it does its path is an uneven and unpredictable mess.

So, we have a pretty good idea that stocks will reward us over time. But we have no idea when, or how, or what it will make us endure in the meantime.

It is a variable interval reward. Which is a hell of a drug.

A common word in Skinner’s research is “seeking.” The rush of variable winning is so strong that seeking the next reward becomes a thrill powerful enough to override sound judgement. Like a pigeon pecking a lever five times per second for fifteen hours, the natural response to not knowing when an important reward will come isn’t patience. It is obsessively seeking.

Which is what we see all the time in investing.

There’s a reason the stock market has 24-7 news coverage but coffee roasting, pedicures, and pretty flowers do not; One has variable rewards, the others have fixed rewards. Same reason the iPhone comes preloaded with a stock market app but not a book-a-massage app.

Look at how often investors check their portfolios.

Or how often they trade.

Or the constant demand for forecasts.

Or the worshiping of gurus.

Investing’s buzz of anticipation comes from knowing that businesses create value, but having markets that are efficient enough to not offer easy rewards. Markets charge you for returns, and they bill you with confusion and noise that make eventual rewards feel amazing.

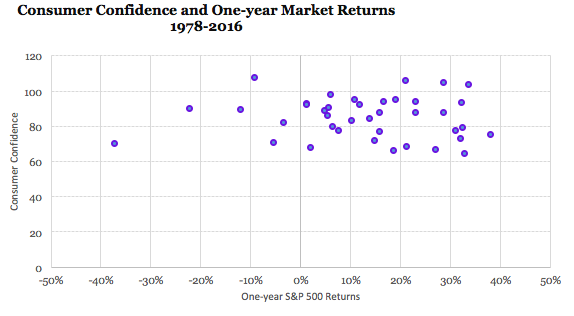

Take the correlation between consumer confidence and one-year market returns. Don’t squint; it doesn’t exist. And it drives people crazy:

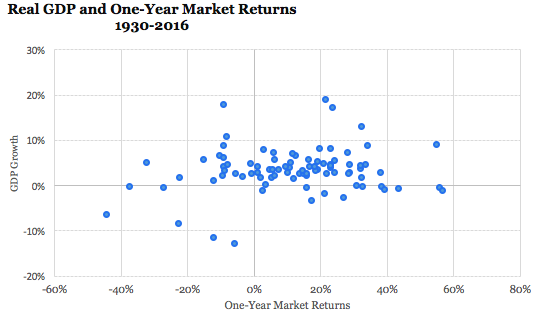

Or market returns and GDP growth. Equally a mess:

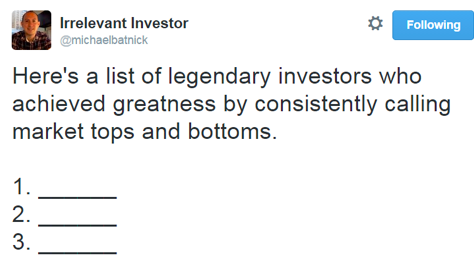

Knowing returns will come is why we have market gurus. But not knowing when they will come is why we have this:

You see this stuff in every form of investing. A high degree of uncertainty and unpredictability is markets’ price of admission, and it’s also the drug that keeps us hooked.

*****

Two things stick out here.

You are probably more interested in the hunting process of investing than you need to be. This varies by how you invest, but it’s true at all levels. There’s too much evidence in all styles of investing that, in aggregate, we put in more effort and intelligence than is necessary. Why we do this make sense when you understand Skinner’s research on variable interval rewards. The buzz of this game is strong enough to keep us searching for the next reward, often obsessively, sometimes to our own detriment. Some rats in these experiments obsessed themselves into exhaustion, frantically waiting for food pellets nonstop for days on end. They wanted food to keep them alive, but they nearly killed themselves trying to get it. Everyone knows an investor like that. A combination of letting time do its work, and humility in how much you can and can’t control, is vital in almost all investing styles.

This is not Excel and charts. It’s dopamine and cortisol. So much of investing is not what you know, but how you behave. And behavior is hard to teach, hard to control, and hard to even come to terms with. There’s uncomfortable truth here: My best guess is that 10% of people are born natural investors, and 10% of people can’t ever be taught how to invest successfully no matter their education. The other 80% of us could improve by spending more energy on how we respond to risk and reward vs. the active chase of searching. Barry Ritholtz was once asked the greatest financial lesson he’s ever learned. “You’re a monkey. It all comes down to that. You are a slightly clever, pants-wearing primate.”

Skinner’s research caused a stir, particularly when he compared pigeon behavior to human tendencies. But “science is a willingness to accept facts even when they are opposed to wishes” he wrote. How we respond to rewards can be more embarrassing than any of us want to admit, but admitting it is how we get better.