When It’s Time To Do Something

The Department of Homeland Security created terrorism warning codes after 9/11. The idea was to attach a label on the level of risk faced at a given moment. There was yellow (significant risk), orange (high risk) and red (severe risk).

Comedian Ron White pointed out the problem. “Does anyone know what to do when the heightened state of awareness goes from yellow to orange?” he asked. “No, you do not. Nobody knows what to do different.”

He proposed a more practical system.

“I’d only have two heightened states of awareness: 1) Go find a helmet, and 2) Put the helmet on.”

Labels that don’t guide action are confusing because everyone has a different perspective on risks and goals. So labels that don’t tell you what to do just give external support to whatever you wanted to in the first place.

This happens in investing, too.

Take the most basic label: short term vs. long term.

There’s no definition of what they mean, or what you should do with them.

Is one year short term? Is five years long term? It depends what you’re doing. I have seen traders call one week the long run and endowments call 10 years the short run.

And even if you say you’re focused on the long run, the long run is a collection of short runs that must at least be dealt with. Take a long-term investor who rebalances after a quick 10% decline. That’s responding to short-term news. So are they still a long-term investor? I don’t know. Or investors with short-term strategies managing for long-term careers. What do we call them? They look like short-term investors, but they may not think of themselves that way if they’re managing money for a retirement that’s 30 years from now.

The blurred lines between time-horizon labels can distort what you think is a competitive advantage. Investor Ben Hunt:

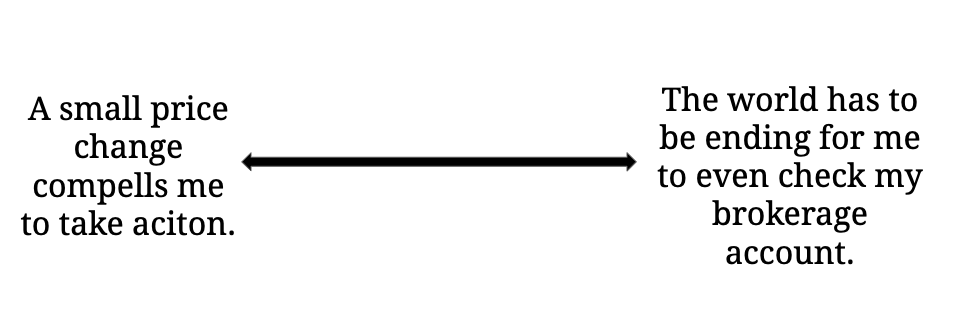

What you and other investors “think about” is arbitrary and often a straw man. What actions you and other investors take is more concrete. So a better label to attach to yourself, and measure others by, is, “How sensitive are your investment actions to new information?”

It’s closer to the Ron White system. Rather than short term on one end and long term on the other, it’s something like this: I consider myself a long-term investor. But a big enough news story could convince me to sell and do something else. It’d have to be a massive news story that changed my view on the economy. It’s a high bar. But it could happen. The biggest criticism against long-term buy-and-hold investing is that it’s oblivious to what’s happening in the world. I don’t think that’s right. Most investors see the same data. Some are just less sensitive to new information than others.

I consider myself a long-term investor. But a big enough news story could convince me to sell and do something else. It’d have to be a massive news story that changed my view on the economy. It’s a high bar. But it could happen. The biggest criticism against long-term buy-and-hold investing is that it’s oblivious to what’s happening in the world. I don’t think that’s right. Most investors see the same data. Some are just less sensitive to new information than others.

Once you separate investors by their sensitivity to new information, the question becomes “How confident are you that the information you’re responding to is signal vs. noise?” That, I think, is the most important question any investor can ask. “Does this piece of information fall into the range of normal stuff I should expect from my strategy, or is it important enough to warrant doing something?”

Most investors are focused on long periods of time. But you can’t build an investing approach based solely off time because, like Ron White, it doesn’t tell you what to do. Knowing your time horizon is important. But it’s more important to know how wide the range of normal variance is in your investing strategy, and only act when stuff falls outside of that range. This is true no matter how you invest – private equity, day trading, and everything in between. Everyone is just after the question, “Does what’s happening in the real world confirm or deny what I expect to happen?”

Answering that question tells you when it’s time to do something.