WeWork Lessons That Apply To Lots of Stuff

No company or investment strategy is proven until it’s survived a calamity. Things that can thrive while the wind is at their back outnumber those that can endure the complete wrath of the real world 100 to 1, at least. Something that’s only viable when everything’s moving in the right direction can – for a while – look the most impressive, because growth during boom times is often amplified by leverage, luck, and obliviousness that can be mistaken for optimism and vision. But markets survive on a steady diet of fragile ignorance, chewing it up and spitting it out whenever it’s exposed. Save your biggest applause for stuff that’s made it through at least one feast.

Independence is one of the most underapreciated assets. Relinquishing it should be done sparingly and with eyes wide open of its cost. Private markets became too confident in the idea that a big fundraising round is synonymous with business success, when in fact the only guarantee that comes from raising tons of money is that someone’s investment gets diluted and a precedent hurdle is set for future rounds. Taking on an unnecessarily large amount of outside capital also increases the odds of getting hooked on other people’s money, stalling a company’s need to create a self-sustaining business until a stranger with different priorities unceremoniously reminds you where the oxygen comes from. Everyone relies on others for something; no one is fully independent, and the right partnership can pay for itself multiple times over. But the ability to do what you want, when you want, with who you want, for as long as you want, has nearly unlimited ROI for both companies and people that can be hard to measure until it’s too late.

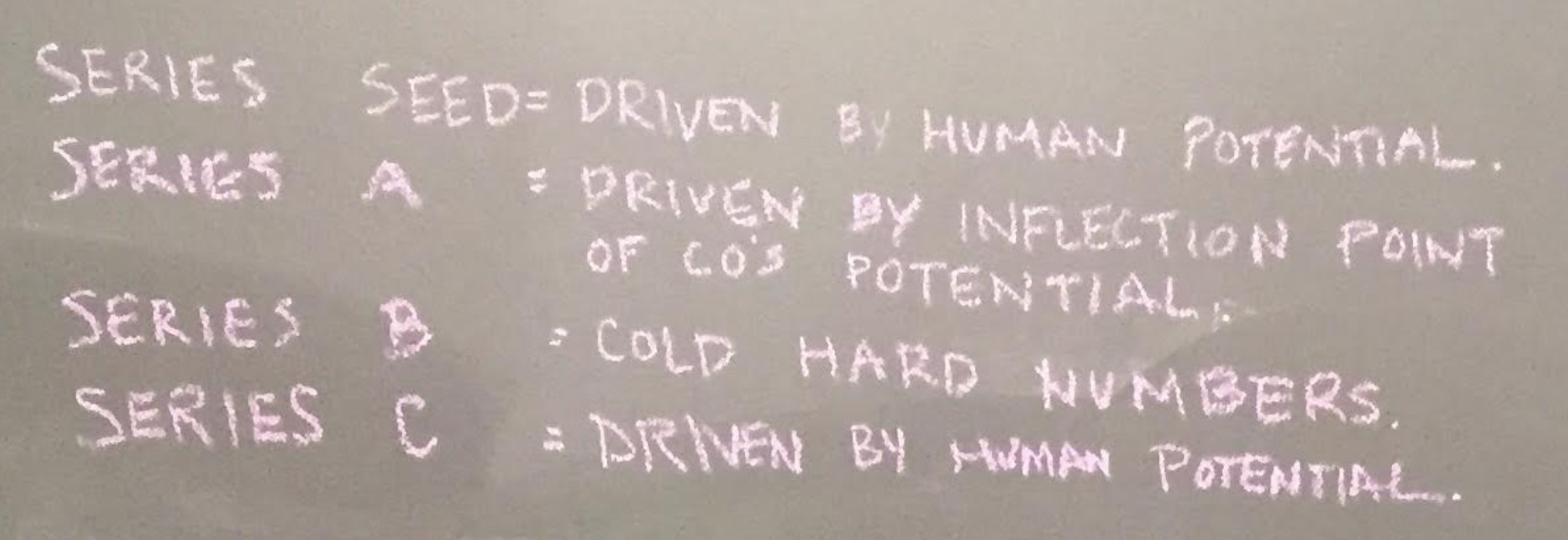

“Magic made them. Only math will save them.” That phrase, by Derek Thompson, applies to many things. Believing in anything about the future means having confidence in something that hasn’t yet materialized. Customers, employees, and investors have to believe in the magic. This is unavoidable and it’s not a bad thing; the opposite – only believing things that are 100% verified – is an economic disaster. But magic only jump-starts the battery. It can’t fuel the car. The baton eventually has to be passed to math. If it’s not, magic that was sold will melt away faster than it came – swiftly and without mercy. We had this sketch in our old office, which I love. Magic has to be verified with cold, hard, numbers:

Everyone wants crazy vision combined with corporate decorum. Rarely are those two things found in the same person. Kanye West said this perfectly: “If you guys want these crazy ideas and these crazy stages, this crazy music and this crazy way of thinking, there’s a chance it might come from a crazy person.” It’s a simple formula: If someone thinks like everyone else they’ll get the same results as everyone else. Since people want abnormal results, they try to find abnormal thinkers. But no one should be shocked when people who think about the world in unique ways you like also think about the world in unique ways you don’t like. If you want the party, you also get the hangover. Big, bold, visions are important and should be celebrated. But they have to be matched with stable, reality-based operators who have equal power if those visions are to have a fighting chance at surviving outside incubation.

Good products do not automatically create good businesses, especially if part of the product’s consumer appeal is that the business sells it for less than the cost of its production. There is a big difference between a company that loses money because it’s investing in the infrastructure needed to become a profitable company, and a company that loses money because it doesn’t charge customers a price that covers the cost of operations. Distinguishing between the two can be clouded by a rapt customer base that creates a cult following around the company and becomes intellectual cover for justifying high valuations. At some point you have to stand on your own two feet, and the longer those first steps are delayed the harder its inevitable day becomes.

Every business has three main stakeholders: Customers, employees, and shareholders. You can ignore any one of those for a while, but eventually all three have to be cared for. Otherwise they’ll revolt, and no company can survive when any one of the big three walks out. Many companies can take care of one, many can do two. But getting all three aligned can is brutally hard, because the easiest way to appease one group is at the expense of another. That’s why the rewards for those that can find the balance are so great.