Ferrari Status

Is Ferrari a car company?

The obvious answer is yes, but not according to its CEO, Benedetto Vigna, who recently described the company’s business model saying,

“We are not – we are not – a car company. We are a luxury company that is also doing cars.”

That’s their differentiator. Their brand. Their “schtick.” And, it works, but not because it’s a marketing ploy. It works because Ferrari backs it up with its actions.

How so?

By adhering to its founder Enzo Ferrari’s “scarcity dictum” that declares,

“Ferrari will always deliver one car fewer than the market demands.”

Delivering one fewer than the market demands —

How many businesses can say they do that?

In my experience, very few. In fact, many do precisely the opposite.

Why?

Because more is almost always considered better. Size, scale, and growth are seductive. It is what attracts new investors and fresh capital. It is what grabs attention and headlines.

The trouble is that size and growth isn’t necessarily synonymous with strong performance.

Look no further than the past five years in the auto industry.

From 2020 to 2024, Ferrari sold fewer than 60,000 cars, but for an average price of over $450,000.

Now compare that with two of the largest car companies in the world by sales and revenue. Since 2020, Toyota has sold more than 52 million cars at an average price of $32,000. Meanwhile GM sold close to 30 million at an average price of $51,000.

As a result, while these behemoths have produced revenue north of a trillion dollars versus Ferraris of less than $30 billion, Ferrari’s net margins have been significantly higher at close to 23% last year versus an average of less than 6% for Toyota and GM.

The gap is even more pronounced on a gross margin basis.

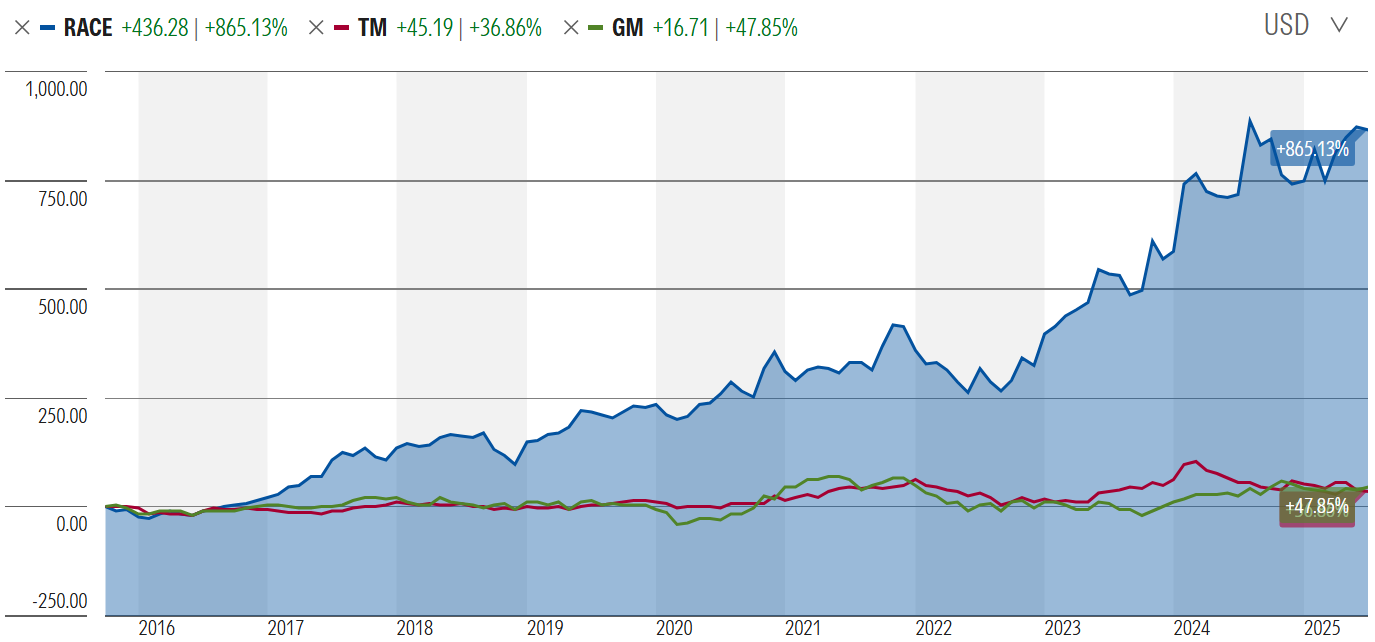

The result has been drastically different stock price performance, as seen in the chart below (RACE = Ferrari, TM = Toyota, and GM = General Motors). Margins matter.

This isn’t limited to the auto industry. In fact, we see it everywhere from retailers to banks to technology companies, among others. Each is littered with failed growth stories, from Abercrombie and Under Armour, to Lehman Brothers and Countrywide, to GoPro, Clubhouse, and Peloton.

Most recently Burberry, the once iconic British fashion company, admitted that it too had fallen victim to unbridled pursuit of global growth. In doing so, it diluted its luxury image by becoming ‘too everywhere,’ which is why its new CEO is currently unwinding many of its most ambitious detours and refocusing on what built the brand. In his words, he wants to “lean into the assets that we already have and celebrate who we are.” Said another way, he wants to return to the Ferrari model.

If so, why don’t more companies follow Ferrari’s lead? Because as J.P. Morgan CEO, Jamie Dimon, is quoted as saying,

“CEO’s feel this tremendous pressure to grow. The problem is that sometimes you can’t grow. Many times, you don’t want to grow because growth can force you to take on bad customers/clients, excess risk, or excess leverage.”

Yet today, the euphoria surrounding growth, scale, and size is palpable. It’s practically all anyone talks about.

Every company wants to be classified as hyper-growth because doing so garners the highest valuations and attracts the most attention. To achieve this, many companies are chasing markets with massive total addressable markets (aka “TAMs”) and limitless opportunities. They prioritize scale and size over everything else. The trouble though, as Bill Gurley of Benchmark Capital recently highlighted, is that this has led to a dynamic akin to a “gavage.”

Never heard of a gavage?

Neither had I, but apparently it is the tube the French use to force-feed ducks to create foie gras.

Today, venture capital firms are doing something similar, but instead of force-feeding ducks with food, they are force feeding companies with capital. In doing so, this is forcing companies to invest in areas outside their circle of competence, hire people to sell products that aren’t ready for “go to market,” and to lose discipline more broadly. In Gurley’s words on a recent podcast titled “The Gift and Curse of Staying Private,”,

“It is forcing every company to go ‘all or nothing’ and ‘swing for the fences.’ It is no longer your grandfather’s startup business or your grandfather’s venture capital fund. It is a radically different world. And if you are a founder, you would like to be able to ignore all of it and build your company the way you want to build it. But if your competitor raises $300 million and is going to 10x the size of their sales force, or 50x it, you will be dead before you know it. You won’t be around. I think it’s bad for the ecosystem because it will remove all the small and middle outcomes and force businesses to just play grand slam home runs. But that’s what it feels like to me. And it feels like we didn’t learn anything from the days of 0% interest rates.”

Unsurprisingly, if this forced feeding of capital is causing companies to be less disciplined in how they allocate capital, there will undoubtably be a negative downstream effect on the venture and private equity funds that are backing them. In fact, we may already be seeing this in the form of diminishing returns and lower liquidity.

Amazingly though, even with the private markets already awash in capital, we are about to witness an even larger inflow in the form of individual investor capital. Look no further than the recent WSJ article titled, “Why Vanguard, Champion of Low-Fee Investing Joined the ‘Private Markets’ Craze,” that highlights how the champion of passive investing has been seduced into the world of alternatives.

Vanguard is far from alone though as KKR recently announced a partnership with the mutual fund complex, The Capital Group, in order to expand its alternative offerings to “non-accredited” investors. Meanwhile, Charles Schwab announced that it is entering the alternatives world in a meaningful way by advocating that they will be incorporated into its 401k and individual investor platforms.

This is nothing new for investors though. It happened to mutual funds in the 1980’s after the advent of the 401k, hedge funds in the early 2000’s following the dot.com collapse, emerging markets after a brutal stretch for U.S. stocks, real estate funds heading into the GFC, and energy funds when commodity prices spiked more than a decade ago. In each case, too much capital proved to be a drag on performance.

Venture capital, and potentially private equity more broadly, will likely be the next victim.

So, what should an investor do?

The simple answer might be to “avoid private equity all together,” but that’s too simplistic and short-sighted. To me, that answer feels like the equivalent of giving up on investing in retail companies all together because Burberry, Under Armour, and Abercrombie overplayed their hands. Afterall, if you did this, you would have missed the Hermes, CostCo’s, Ross Store’s, and Monster Beverage’s of the world.

As a result, it feels like the better course of action is to pursue the funds that aim to achieve Ferrari status. Those that have maintained the discipline to, in Enzo Ferrari’s words, “deliver one fewer (investment or fund) than the market demands,” while avoiding those that have gotten seduced by growth at all costs.

This said, it also feels like there might be even more unique opportunities, especially in the public markets, but that is for a future post.