Little Ways The World Works

If you find something that is true in more than one field, you’ve probably uncovered something particularly important. The more fields it shows up in, the more likely it is to be a fundamental and recurring driver of how the world works.

Take two topics that seemingly have nothing to do with each other: goldfish and tech companies.

Take two groups of identical baby fish. Put one in abnormally cold water; the other in abnormally warm water. The fish living in cold water will grow slower than normal, while those in warm water will grow faster than normal.

Put both groups back in regular temperature water and they’ll eventually converge to become normal, full-sized adults.

Then the magic happens.

Fish with slowed-down growth in their early days go on to live 30% longer than average. Those with artificial super-charged growth early on die 15% earlier than average.

That’s what biologists from University of Glasgow found.

The cause isn’t complicated. Super-charged growth can cause permanent tissue damage and “may only be achieved by diversion of resources away from maintenance and repair of damaged biomolecules.” Slowed-down growth does the opposite, “allowing an increased allocation to maintenance and repair.”

“You might well expect a machine built in haste to fail quicker than one put together carefully and methodically, and our study suggests that this may be true for bodies too,” one of the researchers wrote.

The same thing has been found in humans. And in birds. And in rats.

And isn’t it the same in business?

Chamath Palihapitiya once noted that however fast your business grows, that’s the half-life for how quickly it can be destroyed. So many companies, flush with cheap money from previous years, are learning this right now. Every business and every industry has a natural growth rate – push beyond it and short-term growth comes at the cost of long-term quality, and eventually survival.

When the limits of fast growth impact goldfish and rats the same way it limits tech companies, you know you’ve found an essential part of how the world works, and will continue working in the future.

John Muir once said, “When we try to pick out anything by itself we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” Fields are studied individually, but there are so many common denominators across topics. The more fields a lesson applies to, and the more disparate those fields are, the more powerful and important the lesson becomes.

It might sound crazy, but once you understand the basic principles of your profession, you might gain more expertise by reading around your field than within your field. Connecting dots between fields helps you uncover the most powerful forces that guide how the world works, which can be so much more important than a little new detail that’s specific to your profession.

And if you look hard enough, there are so many dots to connect.

Here’s another.

Part of the second law of thermodynamics is that you get the most efficiency out of a system when the hottest heat source meets the coldest sink – that’s when an engine will waste the least amount of heat, converting as much energy into power as it can.

And isn’t it the same in business and careers?

A genius entering a crowded and competitive field may find a little success, but put her in a “cold” industry full of idiots and she’ll create a monopoly, destroying competitors. Jeff Bezos famously said “your margin is my opportunity,” which is the same concept. The biggest opportunities happen when a hot talent meets a cold industry. Thermodynamics has proven this since the beginning of the universe – no one should doubt how true and powerful it is.

Another:

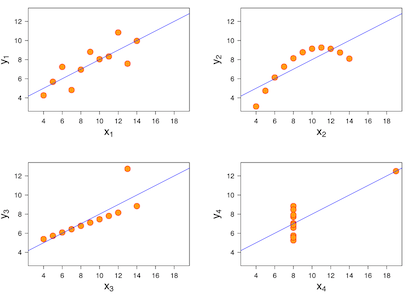

Fifty years ago a mathematician named Frank Anscombe came up with four sets of numbers, each with identical characteristics – the same average, variance, and correlation, down to the decimal point. The number sets are indistinguishable on paper.

But when graphed, each set couldn’t be more different:

It’s called Anscombe’s Quartet, and in math textbooks it’s used to show how precise calculations can skew reality. Anscombe wrote that too many mathematicians are indoctrinated with the idea that “there is just one set of calculations constituting a correct statistical analysis.”

Anscombe, as far as I know, had no interest in economics. But his quartet may be the best way to explain why so many people disagree about inflation.

Part of why inflation sparks heated debates is because everyone spends their money differently, so there’s no single inflation rate – your inflation may be very different from someone else’s, then people get angry that others don’t see what they see. If you have a long commute, you’ll be more sensitive to changes in gas prices than someone working from home. If you’re in college, tuition prices mean everything to you, while the childless retired couple couldn’t care less. Even if you and I have the same overall inflation rate, the paths that get us there leave us with different experiences. If your rent doubles but the price of everything else you buy stays the same, inflation will irk you more than if the price of everything I spend money on goes up by a uniform amount. We are like Anscombe’s sets – looking at precise numbers that in theory are identical but in reality tell different stories.

A few more little ways the world works that I’ve always liked:

Muller’s ratchet (evolution): Dangerous mutations tend to pile up when there’s no genetic recombination, ultimately leading to extinction. It’s is why so few species reproduce asexually. In the absence of variety, bad ideas tend to stick around, which is also exactly what happens in closed societies and large corporations.

Sagan standard (astronomy): Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, in equal proportion. As a corollary: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary scrutiny. Sagan used it as a standard to measure whether extraterrestrials were communicating with Earth, but it applies to almost any field where people get attention, recognition, and money for discovering something new.

Cope’s Rule (evolutionary biology): Species evolve to get bigger bodies over time, because there are competitive advantages to being big. But big has its own drawbacks, and can often be the cause of extinction. So the same force that pushes you to become big can also cause you to go extinct. It describes the lifecycle not only of species, but most companies and industries.

Emergence (complexity): When two plus two equals ten. A little cool air from the north is no big deal. A little warm breeze from the south is pleasant. But when they mix together over Missouri you get a tornado. The same thing happens in careers, when someone with a few mediocre skills mixed together at the right time becomes multiple times more successful than someone who’s an expert in one thing.

Wolff’s Law (anatomy): Bones will adapt to pressure by becoming stronger, or a lack of pressure by becoming weaker. So you never really know something’s maximum strength, because it’s capable of adapting to whatever you throw at it.

Benford’s law of controversy (astrophysics): Passion is inversely proportional to the amount of real information available. When given the opportunity to fill information gaps with rumor, theory, and imagination, people cling to what they want to be true, which tends to be something they are passionate about. The real world is often very boring.

Absorption rates (biology, geology, chemistry): There is a natural limit to how fast something can grow, governed by how fast it can absorb certain nutrients. But different organisms have massively different absorption rates despite being delivered nutrients at the same rate, so you can get vastly different outcomes despite feeding something the same nutrients. Same with education, career success, and social networks – some people are primed to absorb much more than others, even when they are part of the same system.

Galilean Relativity (physics): All physical laws work when you’re moving the same way they do when you’re at rest, which gives two people watching an event different perspectives of what happened. If I’m on an elevator and I throw a ball in the air, to me the ball only rises a few feet. If you’re watching me ride up in an elevator and you see me throw a ball in the air, to you it looks like the ball is traveling faster and higher. Neither view is right or wrong; it’s just relative to another. So to fully understand what’s happening in a system, you have to see it from two perspectives: as an insider, and an outsider. Same in any social system, where an outsider can be blind to internal details but an insider can underestimate the power of tribal affiliations.

Stationarity (statistics): An assumption that the past is a statistical guide to the future, based on the idea that the big forces that impact a system don’t change over time. If you want to know how tall to build a levee, look at the last 100 years of flood data and assume the next 100 years will be the same. Stationarity is a wonderful, science-based concept that works right up until the moment it doesn’t. It’s a major driver of what matters in economics and politics. “Things that have never happened before happen all the time,” says Stanford professor Scott Sagan.

Leibniz’s Worlds (philosophy): There are infinite possible worlds; we just happen to live in this one. Some ideas hold true in all possible worlds, while others would only work in this specific iteration. Naval put it this way: “In 1,000 parallel universes, you want to be wealthy in 999 of them. You don’t want to be wealthy in the fifty of them where you got lucky, so we want to factor luck out of it … I want to live in a way that if my life played out 1,000 times, Naval is successful 999 times.”

Orgel’s rule (evolutionary biology): “Evolution is cleverer than you are.” Whenever a critic says, “evolution could never do that” they usually just lack imagination. When trillions of organisms among millions of species interact for billions of years, the results can be indistinguishable from magic. Same with technology and social trends.

Tocqueville Paradox (sociology): People’s expectations rise faster than living standards, so a society that becomes exponentially wealthier can see a decline in net happiness and satisfaction. There is virtually nothing people can’t get accustomed to, which also helps explain why there is so much desire for innovation and improvement.

Cromwell’s rule (statistics): Never say something cannot occur, or will definitely occur, unless it is logically true (1+1=2). If something has a one-in-a-billion chance of being true, and you interact with billions of things during your lifetime, you are nearly assured to experience some astounding surprises, and should always leave open the possibility of the unthinkable coming true.

Liebig’s law of the minimum (agriculture): A plant’s growth is limited by the single scarcest nutrient, not total nutrients – if you have everything except nitrogen, a plant goes nowhere. Liebig wrote, “The availability of the most abundant nutrient in the soil is only as good as the availability of the least abundant nutrient in the soil.” Most complex systems are the same, which makes them more fragile than we assume. One bad bank, one stuck container ship, or one broken supply line can ruin an entire system’s trajectory.

Three Men Make a Tiger (Chinese proverb): If one person tells you there’s a tiger roaming around your neighborhood, you can assume they’re lying. If two people tell you, you begin to wonder. If three say it’s true, you’re convinced there’s a tiger in your neighborhood and you run for your life. The proverb first came about hundreds of years ago, but is probably more relevant than ever in the social media age. People will believe anything if enough people tell them it’s true.

Look around and you’ll find hundreds of these ideas, linking one field to another. It’s more fun than confining yourself to your own field, and it gets you closer to the truth.