My Most Valuable Season

Guest post by Ted Lamade, Managing Director at The Carnegie Institution for Science

Last month, I was invited to a happy hour near the White House, so after packing up my things, I left the office around 5:30. I walked past the Hay Adams Hotel, in front of St. John’s Church, across Lafayette Square, and eventually found myself in front of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Despite it being a relatively mild afternoon for this time of year, there were few people on the streets, which unfortunately has become the norm for Washington D.C. in this work-from-home era.

I was a little early, so I did what too many people do these days…I grabbed a drink, found a corner of the bar, and started flipping through my phone.

Eventually, I put my phone away and found myself on the periphery of a conversation about millennials and “Gen Z’ers”, when seemingly out of nowhere, someone posed the question, “Do you think these generations are entitled?”

Predictably, one person responded, “Absolutely.” Another griped about their “overstated sense of self-worth.” Another commented how they thought “millennial entitlement was responsible for employee turnover being so high at their company.” Sensing the strong feelings on the topic, I attempted to avoid the crossfire with a non-answer. It quickly fell on deaf ears.

As I walked back across Lafayette Square to grab my car, I thought more about the question, specifically the responses it elicited. Then something dawned on me.

While it’s a bit harsh to label these generations “entitled”, they do have something in common that can give off this impression. Something that binds them. Something that explains the heated responses in the bar — given the strength of the U.S. economy over the past decade-and-a-half, these two generations have yet to experience or witness sustained professional loss (Covid was clearly traumatic, but the recovery was swift given the degree of fiscal and monetary support).

This means that the youngest part of the U.S. workforce hasn’t experienced large scale layoffs, seen what effective leadership amidst a pronounced economic downturn looks like, witnessed strong mentorship during these moments, watched teams rally together, and ultimately seen the impact these experiences can have on their careers. The work-from-home phenomenon has only exacerbated this phenomenon.

The result?

This sustained economic expansion has created two generations that are more confident in their own ability and bargaining position than any in quite a while.

Yet, change might be afoot. If this current economic slowdown persists (especially in the tech world), I expect to see some significant changes in the coming months and quarters, with one of the first being a migration back into the office.

To better understand why and how this could end up being a long-term net positive, let me bring you back to the year 1993 and my most valuable season.

Like most kids, I grew up playing a wide variety of sports. Yet, one I didn’t play until I was nearly a teenager was tackle football. Sure, I played touch football with friends in the neighborhood, threw the ball with my brother in our backyard, and watched games with my father, but I didn’t play in pads until I was about 12.

You have to remember that this was the early 1990’s and kids were playing tackle football as early as third grade, so many of my soon-to-be classmates had played for two or three years at this point. As a result, my father suggested that I needed to “catch up” by joining a local rec league. So, as a 12-year-old football “newbie” I joined the D.C. Police Boys Club #8 team.

My first practice took place on a steaming hot afternoon in late August at Duke Ellington Field across from Georgetown University Hospital. My father dropped me off at the entrance and I walked through the rusting metal gates, across a crumbling track, and onto a field more populated by weeds than grass. The #8 squad was gathering in the far-left section of the end zone, so I headed in that direction.

As I got closer, I noticed someone who appeared to be the head coach. I had heard about Buddy (Burkhead), but had never laid eyes on him before. He had a Popeye the Sailor look to him - late 50s with a deep tan, silver hair tucked beneath a blue hat, and a tight white t-shirt. I slowly walked up to him and introduced myself.

Buddy turned to me and said bluntly, “What position do you play?”

Position?

Having never played before, but knowing I had a decent arm, I replied, “Quarterback” with a surprising level of confidence.

In hindsight, this was a bit presumptuous. Here I was, a kid with zero tackle football experience joining a new team full of experienced players walking up to the head coach declaring I played the most important position in all of sports.

To my surprise, Buddy replied, “Good. You’re our new starting quarterback.”

I was stunned. The new quarterback? In the words of John McEnroe, “He could not be serious.” I quickly learned he was *very *serious when he sent me into the huddle shortly thereafter with a play.

Did Buddy see something special in me? Was this youth football’s version of Bill Belichick drafting Tom Brady in the 6th round? Not exactly….There was a much simpler answer. No one on the team had been willing to play quarterback until I showed up. They knew better. I clearly didn’t.

After some initial apprehension, I became excited about the prospect of being behind center. I was often the quarterback at recess, so how much different could this be?

I would soon find out this was nothing like recess.

A couple practices into the season, I learned why no one wanted to play quarterback. Not only had the Police Boys Club #8 team not won a game in four years, they hadn’t scored a point. Yet, as I would soon find out, it wasn’t for a lack of effort.

Practices were tough. Buddy had us do things that today’s generation of parents wouldn’t tolerate. If we screwed up a play, Buddy would curse and make us run a lap. Screw up again and he would make the entire team run a lap. At times it felt like all we did was run laps.

That said, my clearest memory was how we would often finish practice. The drill was called “Bull in the Ring” and entailed the entire team forming a circle around two players who would hit each other as hard as they could with the goal of knocking the other out of the ring. They were the bulls, and we were the ring.

Better yet, when daylight savings kicked in, Buddy would have the parents drive their cars onto the field and turn their high beams on so that we could run the drill in the dark. Imagine a “Thunderdome” of sorts for sixth graders. It was a different time.

Now, one would think these practices would have prepared me for our first game. One would be wrong.

On a Saturday morning in early September, my father and I got into his light blue Lebaron convertible and drove down to Cardozo High School. Today, the area around Cardozo is in one of the pricier areas in Washington D.C., home to popular restaurants and expensive multifamily rental buildings. However, in the early 1990’s it was known for being a tougher part of town.

When the game started, Buddy sent me out to the huddle with a play. I froze. The guys in the huddle just stared at me as I drew a blank. In a matter of mere seconds, I had forgotten the first play. Not just of the game, but of my life

I reluctantly called timeout.

As I ran back to the sidelines, Buddy wasn’t thrilled, but surprisingly seemed to understand. He called the same play again and I ran back to the huddle. This time, I remembered the play – Buck Sweep Right. I repeated it in the huddle. We lined up and the center hiked the ball. There was just one problem. I went left instead of right, running directly into a blitzing defensive end who resembled Lawrence Taylor. I fumbled. First down going the other way. I ran off to the sidelines with my head down. Buddy was just shaking his.

I honestly don’t remember much about the rest of the game other than fumbling again, forgetting a few more plays, and losing. By a lot. The winless and scoreless streaks were still intact.

When the game ended, my dad and I walked slowly to his blue Lebaron. Not a word was spoken. When we got in the car, I still hadn’t said anything. Finally, my dad asked,

“What’s wrong Ted?”

He clearly knew the answer, but someone had to break the silence. My eyes started to well up and I finally replied, “I don’t want to play again dad.”

“You can quit,” he said.

Knowing his general take on life and that he was a former Naval officer, my father’s initial response surprised me.

I replied, “I can!?!??”

Quickly dashing my hopes, he clarified his response,

“You can quit…but only once the season is over. You have to see this one through until the end.”

Disappointed, I sat there in silence for the entire ride home.

When I got home, I went upstairs to my room. My mom came up a few minutes later. While I was hoping she might let me quit, deep down I knew she wouldn’t.

She didn’t. I couldn’t quit, at least not until the end of the season.

So, there it was. The decision had been made. I had to go back. Back to Buddy. Back to Duke Ellington Field. Back behind center.

A funny thing happened though as the season went on. Practices got easier. Not because Buddy took it easier on us, but rather because we didn’t screw up as often, we didn’t have to run as many laps, and bull in the ring was something we all looked forward to.

As the season went on, we improved. There were fewer broken plays, more first downs, and numerous sustained drives. I’d love to tell you we won a game (we didn’t). I wish I could tell you we scored a point (we hadn’t). Yet, it strangely didn’t matter. In fact, this is something I appreciate more the older I get.

See, despite not scoring a point, running more laps than I can remember, taking big hits, and getting yelled at like never before (or frankly since), that season was invaluable.

Most importantly, despite playing sports for another decade and a half (typically on teams that won more often than we lost), I likely learned more about life in that single season playing for Buddy than I did in all the winning ones combined. I am far from alone.

When Buddy died a few years ago they held a remembrance for him at St. Albans, which is a school in Washington D.C. that he devoted decades of his life to. The gym was packed with hundreds of former players who ranged in age from teenagers to those well into their seventies. It was essentially an “open mike” opportunity for people to talk about the impact Buddy had on their lives.

The sentiment among the players was uniform. Next to their parents, few people had more of an impact on their lives than Buddy. Playing for Buddy was a “rite of passage” according to one former teammate of mine. In fact, to this day, if you run into anyone who played for Buddy and you mention his name, a smile instantaneously forms across their face as they dive into stories about playing for him.

So why do I bring up this winless youth football season from nearly three decades ago? Simply to highlight how valuable losing truly is. The fact is, while winning feels good in the moment, it typically breeds complacency, overconfidence, and stagnancy. On the flip side, while no one likes to lose, it is the essential ingredient to resiliency, humility, and adaptability.

Losing also does another thing. It creates opportunities for young people to turn to mentors like Buddy for guidance. To learn from people who have been through tough times before. To see how these mentors lift a team or organization up when they are down. To observe how they turn a negative into a positive. To see them transform a losing season into one of the most valuable seasons of their lives.

So what does this have to do with the current economy, specifically the issue of getting employees back into the office?

Everything.

The reason this blog is named “A Program that Lasts” is because that is what my alma mater’s head basketball coach, Tony Bennett, said he wanted to build at The University of Virginia. When asked what he needed to build such a program, his response was simple. He said,

“I need young men I can lose with because that’s when you really learn about people. If we can lose together, and we can still survive — to me, that’s the foundational piece.”

The trouble today is that employers have no idea who they can lose with. Outside of the energy sector, it has been a long time since any part of the economy has truly lost. This means that most 20- and 30- year old’s have never truly felt job insecurity. They’ve also jumped around between jobs more than any other generation, so even mentorship in good times is likely foreign to them. For close to fifteen years their services have been in high demand, which is why it shouldn’t come as a surprise that it has been so hard to get these employees back into the office.

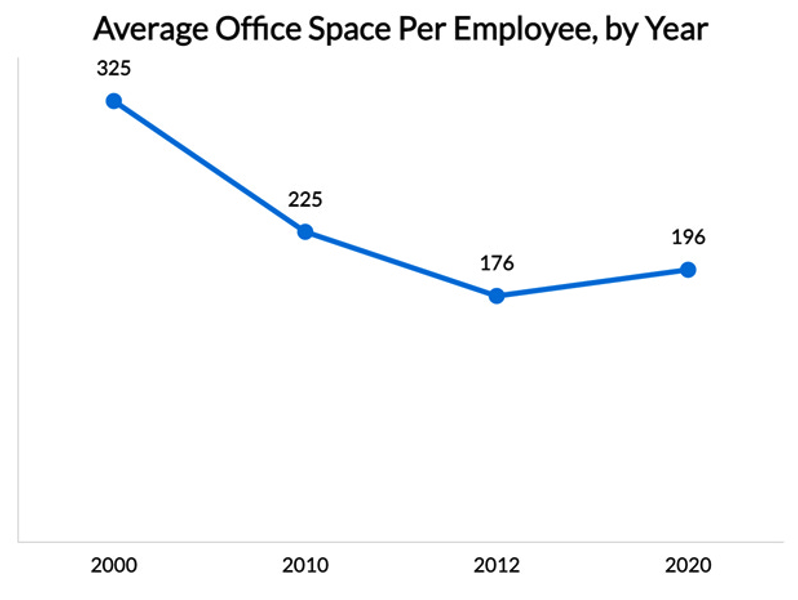

Don’t get me wrong. Companies deserve their fair share of the blame as well for the low office occupancy levels. The fact is, many got greedy when it came to their offices, specifically as it relates to reducing costs. In 2000, the average square footage per employee was over 300 square feet. By 2020, it was under 200 as employers crammed people into trading floor style desks, tight cubicles, and silent shared workrooms, all under the guise of “fostering more collaboration.” This was a quintessential case of short-term gain at the expense of long-term pain.

The result?

Corporate culture and productivity that has been on a gradual decline for years. Covid wasn’t the culprit. It was just the accelerator.

How so?

Look no further than two studies, one performed by the University of Michigan surrounding physical versus electronic collaboration and another relating to the impact outperforming employees can have on their peers.

In Edward Glaeser’s book titled, “Triumph of the City,” Glaeser highlights two separate studies relating to why physical interaction is so important. The first (the Michigan study) challenged several groups of students to play a game in which they could earn money through cooperation and collaboration. Before playing, half of the groups met in person for ten minutes to discuss strategy, while the other half was given thirty minutes to communicate electronically. The findings were clear. The groups that met in person cooperated well and earned money, while the groups that had only connected electronically fell apart. The reason? Team members in the groups that only connected electronically put their personal gains ahead of the group’s needs.

The second was referred to as the “Supermarket Checkout Study.” In it, researchers looked at a variety of checkout clerks’ productivity and performance at a major supermarket chain. The study looked at each clerk, but more specifically, it focused on whether the average clerk’s productivity changed (or didn’t change) when a “superstar” clerk worked during their shift. It turns out that the average clerks’ performance rose substantially when they worked at the same time as the star clerk and fell materially when their shift was filled with below average clerks. This makes sense. The same logic applies to why you work harder with a personal trainer than on your own or run faster against competition than you do on a track alone. People thrive under pressure and in competition. They wither under none.

There is no denying that working from home has created some positive byproducts. Namely, it has increased workers’ flexibility, reduced or eliminated commute times, cut costs (e.g., gas, parking, eating out,), and enabled people to spend more time with their families and friends, just to name a few. Yet, like most things in life, these benefits have not come without a cost.

While many workers claim they are equally (or more) productive working from home, according to the Wall Street Journal, recent data suggests otherwise as labor productivity fell by close to 6% on an annual basis in the first quarter of 2022 (the steepest decline in more than a decade) and by more than 4% in the second quarter, before rising modestly in the third.

While many economists believe worker disengagement is a significant contributing factor in these declines, how can we know for sure whether the work-from-home phenomenon is the main culprit?

My guess?

The answer may reveal itself over the next 12-18 months given that offices in Europe and many parts of Asia have filled back up much more quickly than those in the U.S.

According to JLL, nearly three years removed from the outbreak of Covid, office utilization rates in the United States are still hovering around 50% of pre-pandemic levels, with a number of gateway cities even lower (namely San Francisco, Chicago, Seattle, and Washington D.C.). Meanwhile, utilization rates overseas are reported to be significantly higher at 85+%, with some cities like Stockholm, Tokyo, and London even closer to pre-pandemic levels.

Said another way, the U.S. appears to be on an island by maintaining this work-from-home stance. If this remains the case, pay close attention to productivity levels here versus abroad. If we begin to see European and/or Asian companies diverge from their U.S. competitors, it is hard to envision a scenario where the U.S. can remain on this island.

Yet, with the consensus today believing office occupancy is permanently and irreparably impaired, it is unsurprising that few investors are deploying new capital into the office sector. I get it. I have heard the same reply countless times — “The market is oversupplied”, “There is not enough demand”, “The sector relies on too much leverage”, “There will be structurally less demand for it in the future.”

Yet, after listening to all these reasons not to invest, something dawned on me. They sound an awful lot like the same reasons most investors used to shun another beleaguered asset class a short time ago.

As the Shale revolution peaked and ESG was on the rise, people started to believe the traditional energy sector was on a permanent decline. When Covid hit, people became convinced it was dead. The overwhelming consensus was that the global economy had (a) reached peak demand for oil, (b) fracking had created a glut in supply, and (c) sustainable sources of energy were growing so quickly that they would become the dominant source of energy more quickly than expected. Yet, since then, the picture looks quite different. Since the spring of 2020, the energy sector has produced returns nearly three times that of the S&P 500 for the minority of investors who were brave enough to deploy capital into it.

In recent years, people have said the same sort of things about the office market. Today, everyone is convinced it is dead. The consensus believes we have (a) reached peak office demand, (b) years of overbuilding created a glut in office supply that cannot be worked through, and (c) the work-from-home trend isn’t going anywhere.

However, like that small minority of investors who leaned into the energy sector three years ago, a brave group of investors is starting to circle the office sector. These opportunists and “vultures” have seen this movie before. It is not the first time they’ve heard the “office is dead”. They have witnessed corporate behavior in past cycles, know how employees react during recessions, and understand human behavior. They also know that when cities start to feel the effects of lower tax receipts from depressed office occupancy, reduced office building values, and less retail traffic, new legislation, incentives, and tax proposals to entice companies to return to the office should follow. These investors also know that if they have leverage on pricing and asset selection, they can more appropriately control their fate. If they are right, this will be a very interesting time for office investors.

The question is how will this play out?

I would expect to see it unfold in multiple phases, with three that seem especially interesting.

First, keep an eye on a “One Vanderbilt” phase, which is a reference to the spectacular new building next to Grand Central Station in New York City that is currently commanding more than $300 per square foot and is ~100% leased. Companies most dependent on employees being in the office will want to be in the best, newest, and most environmentally-friendly spaces. This means signing leases in One Vanderbilt-like buildings in cities across the country — highly amenitized, prime locations, and LEED-certified. A notch even above the current “Class A Stock” of buildings.

Given the office market is likely in a “Red Ocean” environment for the near-to-medium term, I would expect these type of buildings to take an increasing share of the existing pie by luring the strongest companies from other parts of cities, commanding premium rents, and even generating longer-term leases from high quality tenants. I could even envision a scenario in which companies eventually decide to take more space and pay even higher prices per square foot if they are successful luring employees back to the office.

The next phase could involve a “Spec Office” strategy. You heard that right. Spec development or re-development. The fact is that there are only so many companies and industries that fit (or can afford) the “One Vanderbilt” model. As a result, I can envision a scenario where a large number of companies look for more creative and flexible ways to lure employees back to the office. To do so, they will likely need to go to their employees. To find workspaces closer to where these employees live. To create unique experiences. As a result, these companies could be looking for highly customized and differentiated offices in unique locations outside of central business districts (think the meat packing district in Manhattan, the Seaport in Boston, the Ball Park area in Washington D.C., and between Buckhead and downtown Atlanta). Or, they could look for “bar-belled” locations where they split the offices — one in the heart of a city with another one (or two) in regional suburbs closer to employees with young families. This is already underway in places like Dallas-Frisco-Ft. Worth and New York-New Jersey-Connecticut. Call it a hybrid solution to a new hybrid work environment.

This is not a new concept. In fact, prior to Covid, these “work-live-play” developments were one of the biggest trends in the market. Yet, it gets less airtime these days. However, given that so many other pre-Covid trends have returned (e.g., desire to travel, preference for “experiences over things”, spiking demand for live events, crowded restaurants, Broadway being back to pre-Covid levels, etc.) there is plenty of reason to believe this trend should return as well. While pricing for these types of assets wouldn’t be dirt cheap, the combination of (a) depressed sentiment around the office, (b) less traditional locations, and (c) the potential to spur economic development, could lead to decent entry points. While lending might be a bit prohibitive these days and construction costs are still elevated, this just means less competition for those that are able to do it.

The final phase is based on price, and price alone. True “crisis investing.” As a result, it will likely take longer to materialize, but at some stage the vultures will circle and deploy capital into a “Third Avenue” phase, which is a reference to the outdated class B or C office buildings on Manhattan’s east side. These buildings are bland, undifferentiated, under-amenitized, and in less desirable locations in many cities across the country. Some of these properties will continue as offices into the future, while others will be repositioned into condos, multifamily rentals, hotels, urban industrial, or other more unique property types like the recently announced Dick’s Sporting Goods ‘House of Sports’ store in Boston or things like Top Golf Facilities.

In the event that we see a significant default cycle, this trend will get accelerated. If so, we could see the rare Ben Graham “cigar butt scenario” in which seasoned investors are able to scoop up assets for heavily discounted prices.

This could unfold many ways, but one example from a prior cycle is what happened in 1970’s when distressed investors bought parts of various REITs’ capital structures at cents on the dollar and collected interest. Then, in out-of-court restructurings, these investors traded them in for new bonds or stock. According to Hilary Rosenberg’s book, Vulture Investors, she highlighted that,

“Buying various parts of specific REIT’s capital structures was a roaring success in areas where investors got the trend right. The real estate market got better, management teams worked themselves out, inflation bailed many out, and they managed to get the banks satisfied. They ended up having an ongoing company with no debt and a big tax loss carry forward and value for the shareholders.”

As a result of these types of actions, this period gave birth to an entire swath of legendary investors, including Sam Zell and Carl Icahn.

There are a lot of doubters out there. Many will scoff. I don’t blame them. It doesn’t “feel” good to invest in the office market today. In fact, after asking a friend to proofread this before I published it, he simply replied with an article titled, “Top Office Owners Don’t Want to Own Only Office Buildings Anymore.” Another friend sent me an article titled, “Work from Home and the Office Real Estate Apocalypse” co-authored by Stijn Van Nieuwerburgh, which is dire to say the least. So is this one in the Economist titled “Business Time - NYC’s Grand Plan” that paints an ugly picture for Manhattan. More recently, Jim Chanos claimed in a recent interview that he is short many parts of the sector given overleverage and stubbornly low cap rates.

My response?

I’d be lying if I said these headlines don’t give me pause. Do I worry about the leverage? Yes. Do I worry about cap rates in various parts of the market? Sure. Will there be more negative headlines, bankruptcies, and damage to come? Most certainly. However, these concerns are more aptly applied to dollars currently in the ground. For new capital, the story is very different. The fact is, this is going to be a bumpy ride, but bumpy rides are what shake the most opportunities loose.

Yet, beyond all the comparisons to past cycles, the energy sector, productivity concerns, and potential financial fallout, what makes me convinced people will be going back to the office? The simple fact that people need to be with people, both during good times and in bad.

Look no further than the recent Harvard study that tracked more than two thousand Americans over 85 years and multiple generations. It concluded that,

“The one crucial factor that stands out for the consistency and power of its ties to physical health, mental health, and longevity wasn’t career achievement, exercise, or a healthy diet. No, the one thing that continuously demonstrates its broad and enduring importance: good relationships.”

I’m no rocket scientist, but I do know it’s awfully hard to build and maintain good relationships virtually. It’s certainly hard to find mentors like Buddy Burkhead.

Is the office dead? I will take the other side of that bet…with new capital and at the right price.