Risk Seeking vs. Mitigating

Guest post by Ted Lamade, Managing Director at The Carnegie Institution for Science

After tapping in for par on the 18th hole at Augusta National with the sun setting behind its towering pines, Scottie Scheffler claimed his second Masters in three years. Shortly thereafter, the prior year’s winner, John Rahm, placed the green jacket on Scheffler’s broad shoulders cementing Scheffler at the top of the world rankings.

As I watched the ceremony unfold, it reminded me of something Scott Van Pelt said last spring when he was discussing Scheffler and Rahm’s respective paths to the top of the sport. Given they had nearly identical scoring averages (~68.6), I figured their paths were very similar. I could not have been more wrong.

See, Rahm’s ascent had come from “risk-seeking”, as evidenced by the fact that he was averaging more than 5.5 birdies per round through the middle of last season and was on pace to become the first PGA player to do so since 2000.

Meanwhile, Scheffler’s success had come from “risk-mitigation”, as evidenced by the fact that he had made a bogey (or worse) on fewer than 10% of the holes he had played. Coincidentally, he was also on pace to do something that hadn’t been done since 2000.

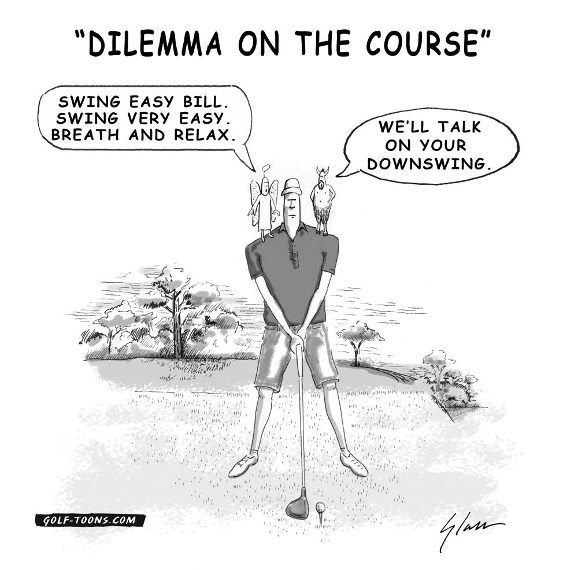

For all you golfers out there, this should be encouraging because it means success can come in multiple forms, so long as you are disciplined enough to stick to what best suits your game. The trouble is few are willing and/or able to do so. Instead, the vast majority of golfers endlessly pivot.

On one hole they choose to be aggressive and attempt to hit a par-5 in two, only to lay up on the next one. They hit aggressive putts on some holes, then lag putts on others. They play it safe and pitch out from behind trees on the front nine, only to attempt aggressive draws around them on the back.

Why?

Because they let their emotions get the best of them.

This is just the start.

Golfers often change their approaches mid-hole, mid-round, mid-season, and sometimes even mid-swing. It’s unquestionably manic. Yet, golfer behavior pales in comparison to investor behavior.

Investors are notoriously mercurial. We chase performance, buy high, sell low, and endlessly pursue fads. Bull markets convince us that we are brilliant, when in reality we are often just pawns in another wealth destroying bubble. Bear markets, on the other hand, force us to do things we had previously convinced ourselves we would never do (namely selling at the lows and stop committing to private investments).

This is precisely the reason why nearly every equity fund’s dollar-weighted returns are significantly worse than their time-weighted returns and why private equity vintage performance is inversely correlated to the amount of capital that funds have raised (i.e., the worst vintages typically come during buoyant fundraising periods). This behavior has been on full display over the past decade-and-a-half.

Like Jordan Spieth’s play in the years after he blew a five shot lead in the final round of the 2016 Masters, investors became incredibly risk averse in the wake of the 2007-2009 great financial crisis (“GFC”) after suffering extreme losses. This meant a strong aversion to riskier asset classes like high growth tech stocks and venture capital. However, as is almost always the case, this aversion waned over time as both started to post strong returns and animal spirits slowly returned.

As the GFC fell further into the rearview mirror, investors began shifting into risk-seeking mode and ratcheted up their exposures to these riskier assets, especially with bond yields so low. It started with modest commitments to venture and tech, but quickly ramped up towards the end of the decade.

For a while, things felt good. Check that, things felt great as the highest growth parts of the market posted eye-popping returns. After all, who doesn’t love the feeling of hitting shots like Phil Mickelson from behind the tree on the 13th at the 2010 Masters or Bubba Watson in a playoff at the 2012 Masters?

The trouble is, unlike Mickelson and Watson who rarely waver from their risk-on approaches, in 2022 when the NASDAQ fell 40% and venture seized up in the wake of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure amid higher rates, investors once again retreated into risk-mitigating mode by failing to add to beaten down tech companies and cutting back on new venture commitments.

When the markets then rallied unexpectedly in 2023 on the heels of the hype around AI and the prospect for lower rates, investors were once again left chasing.

So where does this leave us today?

Investors are once again in risk-seeking mode as evidenced by the fact that individual investors are the most bullish they’ve been since the fall of 2021, the NASDAQ is once again taking in record flows, and investor confidence is so high that buying protection against a 5% dip in the next year has fallen to what Bank of America strategist Ben Bowler called not too long ago the “cheapest you likely have ever seen”. All at a time when the markets look very expensive.

The question is, why do investors continually behave like this?

Simply because it is in our nature.

As Charlie Munger said,

“A lot of people with high IQs aren’t great investors because they have terrible temperaments. That is why having a certain kind of temperament is more important than brains. You need to keep raw irrational emotion under control. You need patience and discipline and an ability to take losses and adversity without going crazy. You need an ability to not be driven crazy by extreme success.”

This quote was top of mind when someone recently asked me whether I thought we should materially dial back risk for an institution I serve on the investment committee for. Earlier in my career, I likely would have responded that we absolutely should dial risk back given the current state of valuations, cheap cost to protect via options, extreme confidence, and looser credit conditions. However, the longer I do this, the more I realize the answer is significantly more nuanced.

The fact is I have no idea where markets are headed or whether there is a greater chance markets will crash or compound at reasonable rates of return over the next few years. No one does.

That said, how did I respond?

I simply said that I thought we should stick to our process.

Now, since this particular institution is conservative in nature, has significant outstanding obligations over the next few years, and no meaningful pending inflows of new capital, this meant that yes, we likely should be more defensive and dial back our risk (the same could be said for a 70-year old retiree with no incoming cash flows or someone looking to retire in the next few years).

However, if this institution had a more “risk on” nature, few (if any) future fixed obligations, and a reliable stream of capital inflows, I would likely have said that it did not make as much sense to significantly dial back risk — namely to skip venture capital commitments, rush out of equities into bonds, etc. (the same could be said for a person early or in the prime of their careers with decades left to work and generate income). The reason is simply because doing so would mean straying from its process, timing the market, and maybe most importantly, forcing a future decision on when to switch back into risk-seeking mode…something few can do effectively.

So, what’s the bottom line?

Investing is hard, but it doesn’t need to be as hard as people make it. As John Rahm and Scottie Scheffler illustrate, success can come in very different forms, so long as you consistently adhere to your process.

Risk-seeking and risk-mitigating can both be successful strategies, so long as you are disciplined enough to stick to them. So today, while the market feels a bit frothy, inflation remains stubbornly high, and the risk to the downside feels greater than the potential to the upside, history has shown that trying to materially adjust your approach to fit the current environment as opposed to your unique circumstances doesn’t typically work out well. Only the very elite (or lucky) investors have shown an ability to toggle between risk-seeking and risk-mitigating.

Now before you go thinking you might be elite, remember when I said earlier that both Rahm’s 5.5 birdies per round and Scheffler’s <10% bogey threshold were coincidentally last accomplished in 2000? Care to guess which golfers accomplished those thresholds close to two-and-a-half decades ago?

Well, what if I told you it wasn’t multiple golfers?

What if I told you it was just one?

Tiger Woods.

So, unless you are the investing equivalent of the greatest golfer of all-time, it probably makes sense to stick to one or the other.