The Locker Room

Guest post by Ted Lamade, Managing Director at The Carnegie Institution for Science

I have played on a lot of teams in my life. Along the way, there have been a number of winning seasons, but just a few that ended with a championship. The winning seasons were nearly always a matter of talent. If we had more of it, we typically won more than we lost. If we had less, we did not. Since talent tends to be the defining factor in most competitive pursuits, this should not come as a surprise. What is less obvious, however, is what drove those special championship seasons.

Growing Up

When I played little league baseball, football, and hockey growing up, the gap between the best and the worst players was enormous. Some kids could barely swing a bat, throw a ball, or skate, while other kids could hit a curveball, throw a perfect spiral, and/or skate backwards with ease. As I got older though, the gap narrowed….a lot. Many of the weaker players quit and some of the best players regressed, but the biggest difference was that the competition increased dramatically as those who kept playing got better and a crop of talented younger players kept emerging. This pattern happens in nearly every sport and each generation. Just look at U.S. swimming legend Michael Phelps. At his peak, he held close to 30 world records. Today, just a decade later, that number is down to 4, including just 1 individual record. I did not give this dynamic much consideration when I was younger, but it is something I think about a lot as an adult.

As we age, it becomes increasingly clear that talent only gets us so far. Whether it is in sports, school, business, investing, or countless other competitive pursuits, the increase in the concentration of talent makes it more difficult to differentiate ourselves on talent alone. Look no further than Harvard’s class of 2024 class. Among its 29,000 applicants, it included 8,500 perfect GPAs, 3,500 perfect SAT math scores, and 2,700 perfect SAT verbal scores, despite the fact that Harvard only accepted ~1,700 students. Or at the fact that there are over 12,000 college football players in a given year who are all heavier, faster, and stronger than the vast majority of the players that came before them, yet still only ~200 will be drafted into the NFL (~1.6%). Intelligence and athleticism at the highest levels are no longer enough.

This creates an interesting dilemma. While someone may be improving on an absolute basis, they are often getting worse relative to their competition. Michael Mauboussin refers to this concept as the “Paradox of Skill”, which simply means that even though people may becoming more skilled at a certain pursuit, it is often more difficult for them to succeed because their competition is also becoming more skilled. This means that eventually the most talented people end up competing against one another, making it very difficult to become a bonafide superstar. Hence the paradox.

Given this reality, what should talented people in competitive industries do? Mauboussin suggests they should “pursue easier games”. Intuitively, this advice makes a lot of sense. If you seek out less talented people to compete against, your chances of success should increase. But what if there are no easier games to play? Or, what if you are not able to or want to play a different game? If I told one of my sons to quit playing soccer, lacrosse, or flag football and go play tiddlywinks because they would have a better chance of being a star, they would tell me to go pound sand. The same goes for public equity investors. Sure, there might be less competition selling residential real estate, coaching football, or investing in private companies in more remote parts of the world, but are these types of options realistic or desirable? For many, I would guess not.

So, if either my sons or a public equity investor were to recognize that talent alone may not be enough, easier games are not a realistic option, and/or they want to keep playing their current games despite the challenge, what would I tell them? I would advise them to keep pursuing what they love, but to seek out teams with great “locker rooms” to pursue them with. Doing so will give them a long lasting edge that isn’t talked about nearly enough.

A Team’s Composition

Many U.S. sports fans agree that the greatest victory in this country’s history was when a group of unknown college kids, led by head coach Herb Brooks, stunned the Soviets 4-3 in the 1980 Winter Olympics and went on to win the gold medal in ice hockey.

When asked how he assembled the team, as well as his University of Minnesota hockey teams (Brooks had taken Minnesota from a perpetual doormat to winning three Division 1 National Championships in 7 years), Brooks responded,

“The key to my recruiting was that I looked for people first, athletes second. I wanted people with sound value systems because you cannot buy values. You are only as good as your values. I learned early on that you do not put greatness into people…but somehow try to pull it out.”

If you have ever played athletics, you know exactly what Brooks is talking about. A great locker room brings out the best in people. It elevates the true leaders, convinces those with selfish streaks to put them aside, and enables a team to play beyond their talent level. Most importantly, when things are not going well, a strong locker room is what allows you to look each other in the eye and know you are going to turn things around.

When you are in one of these locker rooms, it is obvious. You can feel it. However, the trouble is that if you are not, you cannot.

The Business Locker Room

In business, a firm’s culture is its locker room and, I would argue, the most important determinant of long term success. Look no further than a discussion AirBnB founder Brian Chesky had with Peter Thiel. Chesky recounted that,

“After we closed our Series C with Peter Thiel in 2012, we invited him to our office. Half way through the conversation, I asked him what was the single most important piece of advice he had for us. He replied, ‘Don’t f*ck up the culture.’“

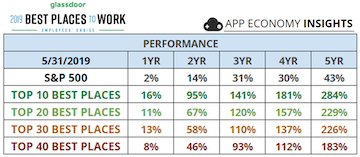

Thiel is far from alone. Sequoia Capital, widely regarded as the world’s best venture firm, has a section on their website titled “Seven Questions With”, which is a series of interviews with various partners, executives, and investors. In nearly every interview I have read, “culture” is referenced as the most important contributor to a company’s success. Jamie Dimon has mandated that JP Morgan employees return to the office, presumably due to concerns about the work-from-home impact on the firm’s culture. Legendary investor Steve Mandel recently commented that the number one thing his mentor, Julian Robertson, taught him was how important people are, starting with their integrity. Bill Ford of General Atlantic and Orlando Bravo of Thomo Bravo said something similar in recent interviews with Ted Seides on Capital Allocators. Maybe most notably, there appears to be a growing correlation between companies’ stock prices and their Glassdoor reviews.

A Model Locker Room

One of the most difficult parts about determining whether a team, fund, or company has a good culture is that there is no such thing as a model “locker room”. They come in all shapes and sizes. In my experience, some have leaders with the ability to motivate and unite the team, others have strong entrenched cultures created by prior generations, while others fit somewhere else on a vast spectrum of organizations. There is no magic formula.

I meet with a lot of funds and investors as a part of my job. For every one that we choose to partner with, we will often meet with more than 100 others. Almost all are full of talented people with impressive resumes and degrees, so checking the box for talent is relatively easy. This is no surprise given the fact that institutional investing is one of the more competitive careers one can pursue. The hard part is determining what is behind these resumes and track records because this is where a key edge and source of endurance resides.

So, why is it hard to identify the strong “locker rooms”? Because it is not easily quantifiable. As data has proliferated, the vast majority of people have become obsessed with what they can quantify. In baseball, this equates to “Moneyball Stats” (on-base percentage, walks, etc.). In basketball, it is three point percentage and possessions per game. In investing, we have wrung the stats towel so tightly with measurements like the sharpe ratio, beta, alpha, PME’s, and r-squared that my head spins when I read through attribution reports. It is not that statistics are not helpful. It is just that in isolation, they do not tell us much about whether a fund will be successful five, ten, and fifteen years down the road.

What to Look For

Since there are no hard and fast rules regarding what defines a strong locker room or a culture, my preference is to keep it simple at the start. I ask everyone I meet with the first time to define the source of their “edge” and “endurance”. I want to hear why they think their fund has an advantage and why this edge is sustainable? More importantly, I want to see if there is consistency or dispersion in the team’s answers.

A few of the positive indications I look for are (a) shared ownership in the business, (b) low employee turnover, (c) diversity of thought, experience, and backgrounds, and (d) an aligned incentive structure. Dig a little deeper though and there are some less obvious indications of a good locker room. Namely:

Mentors – Does the firm prioritize mentorship? Do employees feel like they have advocates within the firm? Do the mentees eventually become the mentors?

Trust – Do people at the firm trust those around and above them? If younger employees look left and right in a meeting, do they admire these people? Do they aspire to be in their bosses’ shoes in the future?

Strategy – Do the “higher ups” value their employees’ opinions? Do they encourage open discussions or do they “steer” the conversation? Do they value differing opinions or just say they do?

Recruiting – What types of qualities does the firm prioritize when hiring? How much emphasis is placed on character versus sheer intellectual horsepower? Where do they recruit from?

Accountability – How has the firm handled disruptive colleagues? Are the most talented colleagues given exceptions or are they held to the same standard? How are good team players acknowledged and rewarded?

In each case, the more examples, the better.

These are not hard and fast rules. There never are. They are just some of the observations I have made after spending considerable time in a wide variety of locker rooms and offices.

A Long Season

Most careers, investing in particular, have plenty of highs, a number of lows, and a lot of mundane moments that fall somewhere in between. The high and mundane periods have a tendency to take care of themselves. The lows are what define you and the relationships you choose. They are the moments you realize how important your locker room is. Or, as Doug Leone, the current managing partner of Sequoia Capital, recently said in response to a question about how and why Sequoia was able to escape the dot.com bust with positive numbers, unlike the vast majority of venture firms.

“It was a sense of camaraderie. It was the fact that each one of the cells in our bodies could not do that (walk away from those funds). It had nothing to do with, ‘we have to save our careers, our money, none of that’. It had to do with being a badass and doing what nobody else would do. That’s what it had to do with. Doing the right thing when it’s inconvenient for you.”

The tough times are the ones that make you realize how much you cherish having teammates and partners who are going to get you to the other side because this is what truly adds long term value.