Who Pays For This?

The federal government will run a $3.8 trillion deficit this year and $2.1 trillion next year.

Those estimates, from a budget-focused think tank, don’t include what’s almost certain to be another multi-trillion-dollar stimulus package or two, or three, in the near future.

We’re all just guessing, but when this is all over – however you want to define that – it would not surprise me if the direct federal cost of Covid-19 is something north of $10 trillion.

I’ve heard many people ask recently, “How are we going to pay for that?”

With debt, of course. Enormous, hard-to-fathom, piles of debt.

But the question is really asking, “How will we get out from underneath that debt?”

How do we pay it off?

Three things are important here:

-

We won’t ever pay it off.

-

That’s fine.

-

We’re lucky to have a fascinating history of how this works.

The history starts – as so many important things do – with World War II. It’s the only era in American history with budget figures comparable to today’s.

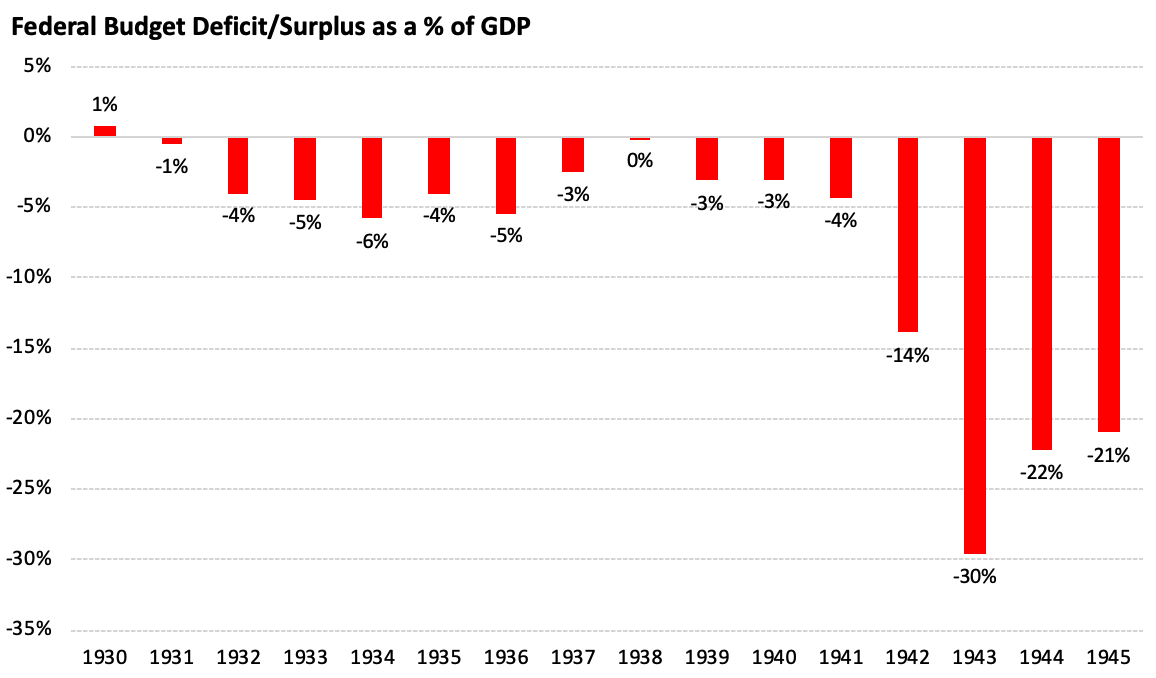

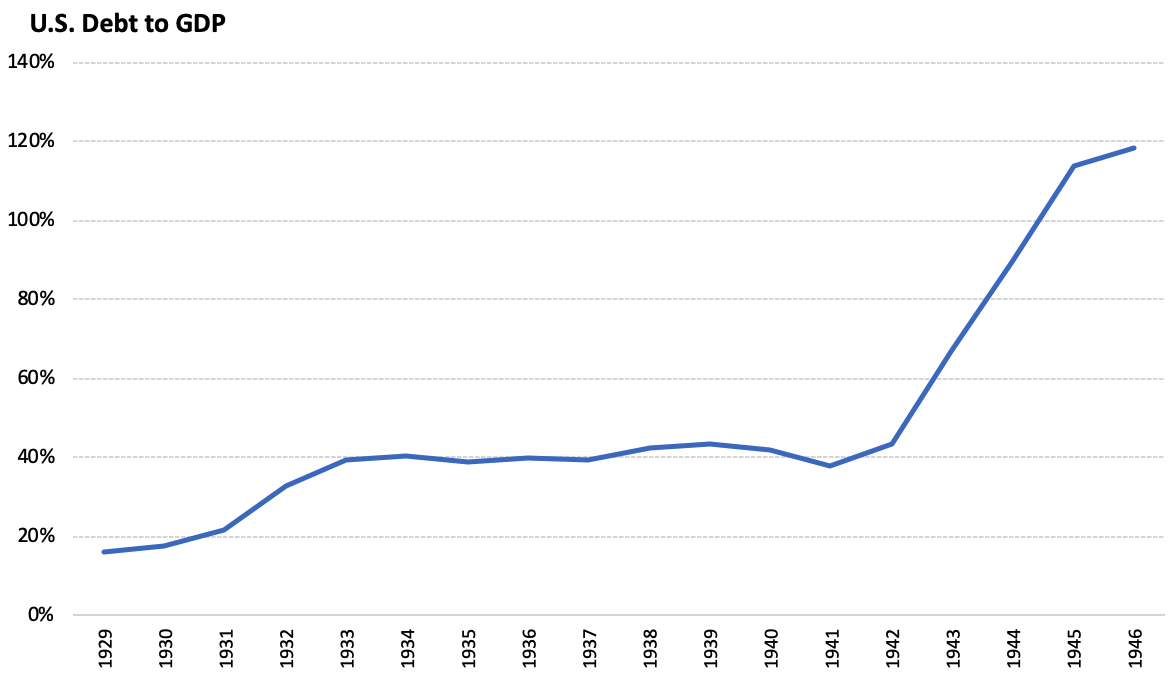

The budget deficit hit a record in 1943 at 30% of GDP. This year’s deficit, around 19% of GDP, will be equivalent to the deficits run in 1944 and 1945, also during the peak war years. Federal debt as a percentage of GDP is on track to exceed its previous record, set in 1946, next year.

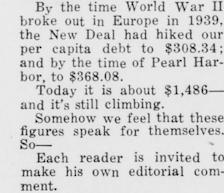

War-time debt in the 1940s freaked people out just like today’s debt does.

In 1944 a University of Illinois economist named Frank Dickson wrote a popular op-ed arguing that the only way the United States could survive economically was to default on its $200 billion of war-time debt. Otherwise, he said, a whole generation would spend their entire careers working to pay off the national debt.

In June of 1944 – a week after D-Day – one Illinois newspaper suggested the debt figures were too absurd to even comment on:

In 1946 the Council of Economic Advisors delivered a report to President Truman warning of “a full-scale depression some time in the next one to four years.” A major reason, they wrote, was the enormity of the national debt that would snuff out all economic progress.

None of it came to pass.

By the early 1980s federal debt as a percent of GDP was at the lowest level in half a century, and below where it was when the war began.

The war was effectively paid off, and the economy boomed in the process.

The calamity never happened.

Here’s what did happen.

FDR told Americans in 1941:

We must fight this threat wherever it appears; and it can be found at the threshold of every home in America.

And so my fellow Americans, I ask you to demonstrate again your faith in America by joining me in investing in the new defense savings bonds and stamps. I know you will help.

The amount of debt needed to finance the war was unlike the nation had seen before

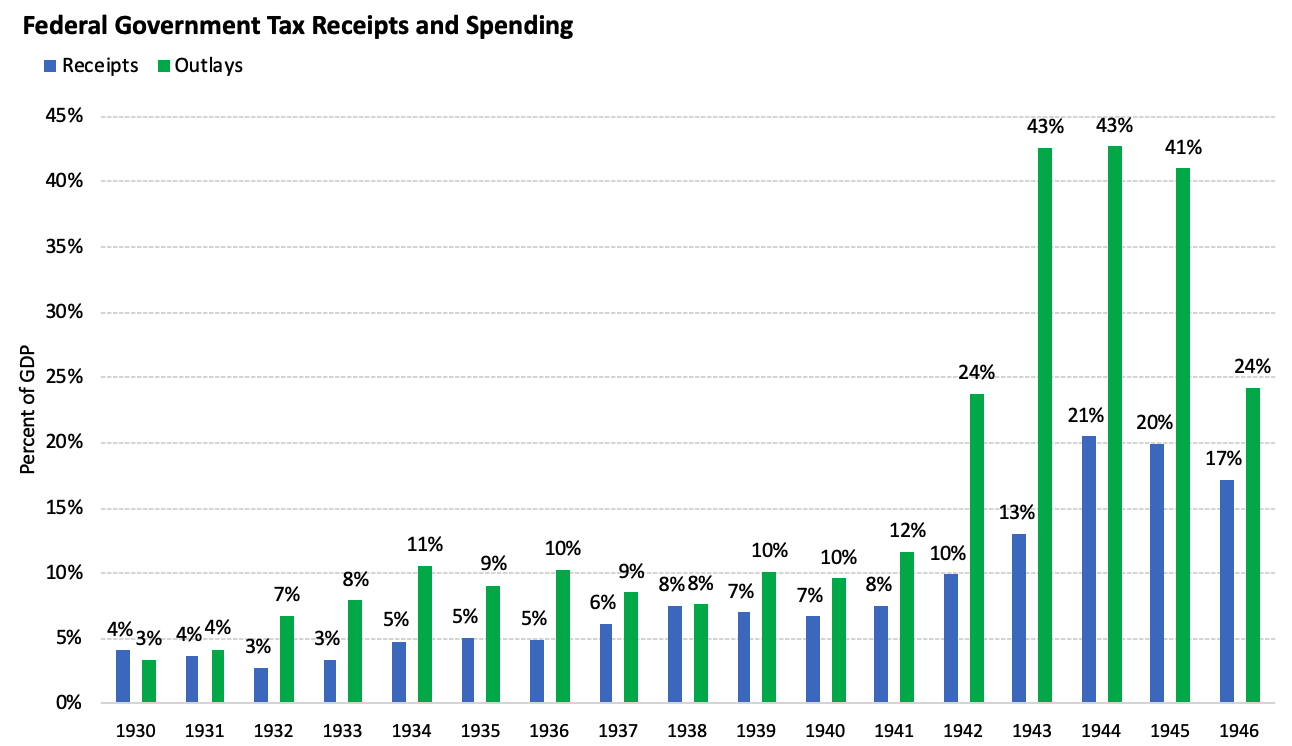

Government spending as a share of GDP rose ten-fold in a decade. Tax revenue rose five-fold:

Deficits were five times higher than anything seen during the New Deal in the 1930s:

Government debt as a share of GDP rose six-fold:

You can imagine how daunting this was at the time. There was no precedent, and it occurred at a time when the Great Depression left everyone fearing the wrath of excessive leverage.

Two things happened at the end of the war.

1. Taxes were kept high. Before the war, tax revenue as a percent of GDP had never been higher than 7.8%. Since the war it’s averaged 14%, and has never gone below 11% in a given year. The top marginal tax rate went from 24% in 1929 to 94% by 1945, and would not drop below 80% for another 20 years.

FDR told the nation in 1941:

It is not a sacrifice for the industrialist or the wage earner, the farmer or the shopkeeper, the trainmen or the doctor, to pay more taxes, to buy more bonds, to forego extra profits, to work longer or harder at the task for which he is best fitted. Rather it is a privilege.

2. Spending never returned to pre-war levels. Before World War I government spending as a share of GDP hovered around 3% per year. During the peak year of the first world war it hit 21%, but quickly fell back closer to historic norms. The second world war was different. Spending surged to more than 43% of GDP in 1944. When the war ended it never reverted back to its pre-war levels, averaging about 17% of GDP – four times its pre-war level – for the next 80 years. Things like the Cold War, the GI bill, and modern infrastructure kept government spending higher than people could ever imagine for longer than people ever expected.

Put those two together and something interesting happened.

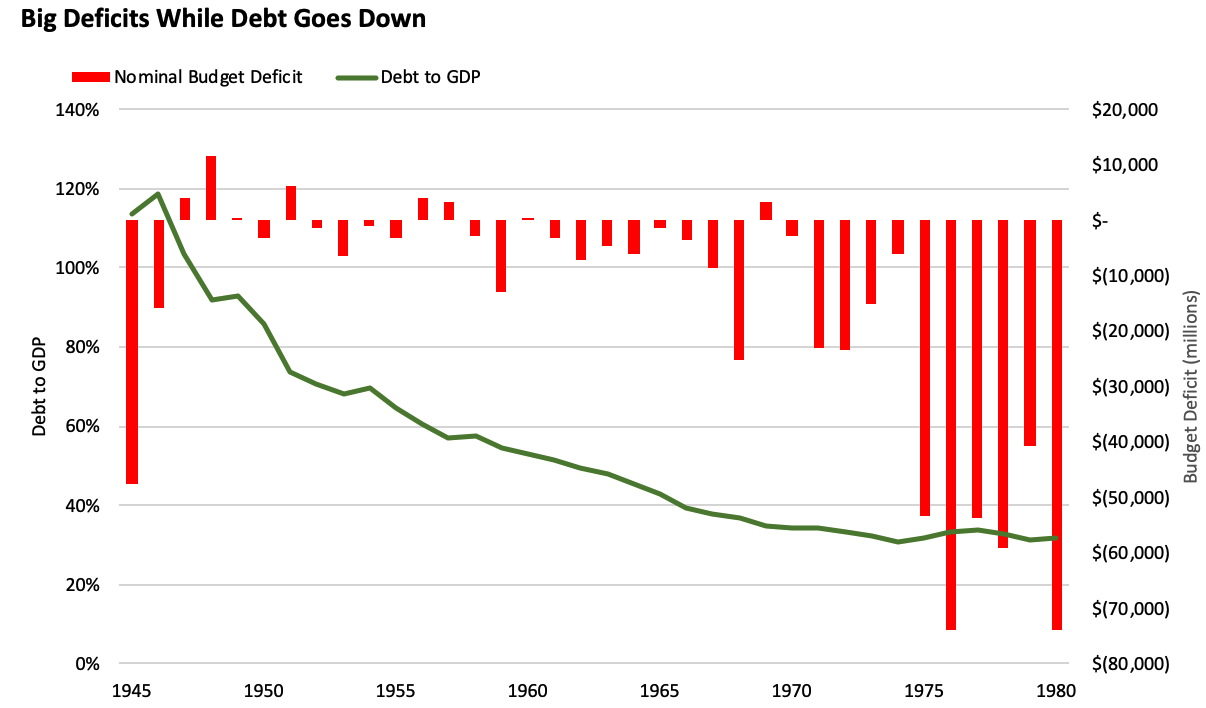

By 1985 World War II debt had effectively been “paid off,” with debt to GDP returning to post-war levels. But between 1945 and 1985 the federal government only ran a budget surplus in six years, all of which were basically accounting quirks. Since 1950 federal debt has increased every year.

World War II debt was never repaid, at least at the aggregate level. Old bonds were repaid with new bonds. But debt kept rising.

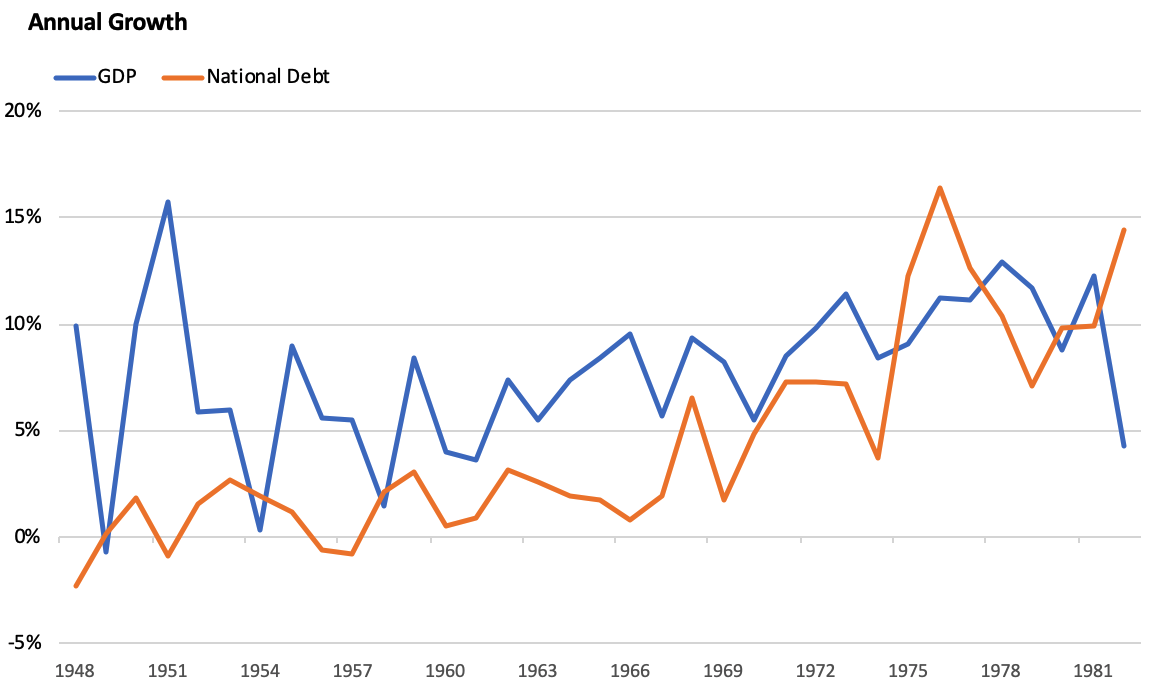

It was “paid off” in the sense that the economy grew faster than new debt accumulated:

So over time, debt-to-GDP fell even with deficits year after year:

That’s how government debt gets repaid after it piles up. You don’t pay it off. You grow your way out of it.

This isn’t intuitive because it doesn’t apply to people. When a person takes out a mortgage or a car loan, there’s a repayment date. But that’s only because people have finite careers and lifespans, so there’s an “end date” where all debts have to be repaid.

Countries (and to some extent companies) are different. They have indefinite lives. So they can remain indebted indefinitely, even with rising debt.

As long as nominal GDP growth is higher than the annual budget deficit, debt to GDP goes down, and spending more than you take in leaves you with a lower debt burden.

This is so simple, but it’s easily overlooked because it doesn’t apply to people.

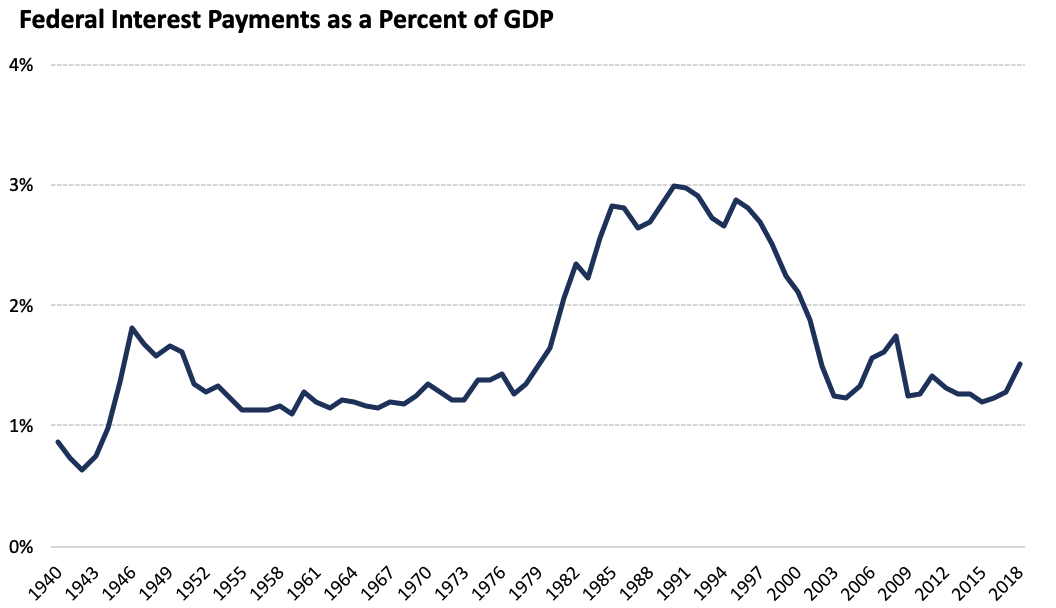

What matters for countries isn’t the amount of debt they hold. It’s how burdensome that debt is to maintain over time.

The burden of our national debt – interest payments as a share of GDP – has been in a fairly tight range since the end of World War II. The burden wasn’t much different in 1950, when debt was near its peak, than in 1940, before the war began. It’s at about the same level today, 80 years later:

As many panicked at our national debt at the end of the war, a 1945 article in The Wall Street Journal was prescient. “There is little likelihood that the national debt will be reduced substantially during the next generation,” it read. “This means that debt management rather than debt reduction is the important problem before the Treasury in the coming years.”

Same thing today.

History never repeats. We can’t automatically assume we’ll be able to grow out of Covid-19 debt like we did after World War II. A lot of things globally and demographically happened after the war that gave a tailwind to growth. Some of those forces are now headwinds.

There are so many questions.

Will interest rates stay low?

Will we avoid another catastrophe that requires trillions of new debt?

How much of growing out of our debt will be inflation vs. real growth?

I don’t know the answers. No one does.

But when people say, “We’re leaving this debt for our kids and grandkids to repay.” Well … probably not.

This isn’t a mortgage that has to be paid in full by a specific date. Without repaying a cent of the debt, its burden could easily be less in another generation than it is today.

We’re all guessing. But my best guess is that sometime in the next few years we’ll have the biggest tax increase since the end of World War II, regardless of who’s president. Spending will come down from current levels but stay higher than it was before the crisis as enhanced unemployment benefits become permanent. Debt will never actually decline; it will rise every year.

But if we’re lucky – that’s the right word – the panic-induced innovation that comes from Covid-19 will spark enough eventual prosperity to let us maintain or grow out of this debt, like we have before.

(All data from Office of Management And Budget and Federal Reserve).