Why New Technology Is A Hard Sell

Let me tell you about the only time in history a new technology has been adopted by almost everyone virtually overnight.

Polio killed 3,145 Americans in 1952. Almost all were kids. It left tens of thousands in wheelchairs or confined to iron lungs, where one described his existence as “walking a thin line between life and death.” The most famous American of the era, Franklin Roosevelt, was a poster-child of its wrath.

Polio’s infamy made its vaccine trials a national suspense. David Oshinsky writes in his book Polio:

A Gallup poll showed that more Americans were aware of the field trials than knew “the full name of the President of the United States.” By one estimate, two-thirds of the nation had already donated money to the March of Dimes by 1954, and seven million people had volunteered their time. Never before had Americans taken such a personal interest in a medical or scientific pursuit.

Tuesday, April 12th, 1955 – the 10-year anniversary of Franklin Roosevelt’s death – brought the news. Dave Garroway was the first to report on NBC’s Today show. “The vaccine works,” he told the nation. “It is safe, effective, and potent.”

Oshinsky writes:

The suspense was broken. Schoolchildren and factory workers got the word over public address systems. Office workers heard it while huddling around radios. In department stores, courtrooms, and coffee shops, people wept openly with relief. To many, April 12 resembled another V-J Day—the end of a war. “We were safe again,” recalled author Frank Deford.

What happened next is incredible, because it’s so rare in the history of new technology: Tens of millions of people around the world lined up and said, “I want that, and I want it right now. Stick the needle in my arm, let’s do this.”

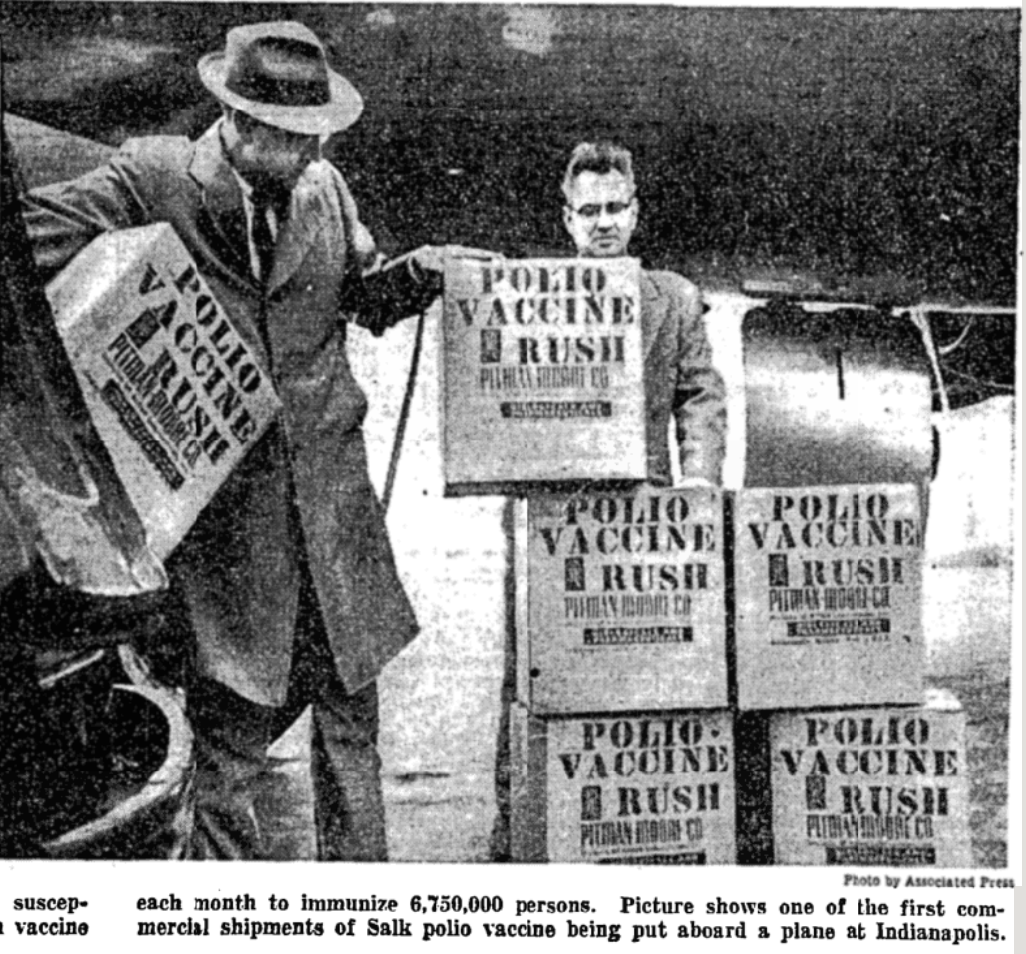

Soon after the polio vaccine was announced Congress funded a grant to ensure “that every child and expectant mother has the opportunity” to be vaccinated. The urge to vaccinate everyone as soon as possible was so high that the government awarded licenses to manufacturers without the standard review or supervision, leading to botched batches that killed 11 kids.

Fifty-seven million doses were delivered within six months.

Eighty-seven million Americans – the vast majority of kids and pregnant women – were vaccinated within four years.

It did not stop at our borders. In 1959 the Soviet Union vaccinated 77 million people, everyone under age 20.

The polio vaccine is an outlier in the history of new technology because of the speed at which it was adopted. It is perhaps the lone exception to the rule that new technology has to suffer years of ignorance before people take it seriously. I don’t know of anything else like it.

You might think it was quickly adopted because it saved lives. But a far more important medical breakthrough of the 20th century – penicillin – took almost 20 years from the time it was discovered until it was used in hospitals. Ten times as many died in car accidents as from polio in the early 1950s, but it took half a century for seat belts to become a standard feature in cars.

That gap is the common story of technology. It was years after the Wright Brothers’ first flight before people paid attention, let alone considered flying. Same for the car, the telephone, the computer, the internet, the index fund, solar power, and virtually every other great technology you can think of. It usually takes more time to convince people that your technology has changed the world than it does to invent a world-changing technology. This is easy to overlook because we implicitly assume a technology began around the time we started using it. But most were created years, even decades, before they caught on.

I don’t think we can say exactly why the polio vaccine was adopted quickly. A public awareness campaign by the March of Dimes and the spotlight on President Roosevelt helped.

Whatever the reason, it was an outlier. New technology is almost always a hard sell.

Why?

Why aren’t more new technologies adopted as quickly as the polio vaccine?

Two obvious answers are that most new technologies aren’t ready for primetime, and incumbents with deep pockets keep competition at bay.

But there are a few other overlooked explanations for the gap between new technology and consumer adoption.

Here are four.

1. Convincing people that you can solve their problems is harder than it seems because people don’t want to be told that the way they’ve always done things is wrong.

We can look back in shock at how primitively people lived 100 years ago. No air conditioning. No computers. Few cars. Barbaric medicine – on and on. It looks miserable.

But few people in 1919 knew how bad they had it. They thought they were living in a technoutopia. They weren’t comparing their lives to 2019; they were looking at how things had changed for the better since, say, 1880. A hard thing when studying history is how blinded you become to hindsight bias. It’s easy to assume everyone in the past was dying for new technology to come along and end what we, today, consider to be suffering. But in real time people don’t want to think they’re suffering, partly because they don’t know what future technology they’re missing. The idea that you have a better way to do something is a harder sell than you might think because most people, when comparing their lives to the past, think the way they do things now is pretty good.

Take the car. You might think its arrival would spark joy over how much better life would become. But at first a common response was to say, “No thanks. I like my horse.” On August 23, 1897, a letter to the editor in the New York Times responded to the idea of owning a car:

Sensitive and sentimental folk cannot view the pending change without conflicting emotions. There are reasons why the departure of the horse from the streets and the park drives should be considered gratifying. But it must be confessed that he will take with him a kind of picturesqueness which the self-motivating wagon will never supply. Moreover, man loves the horse, and he is not likely ever to love the automobile …. Nor will he ever get quite used to speeding along the road behind nothing. The gracefulness of the horse will be sadly missed for a long while, and the afternoon pageant on Bellevue Avenue in Newport will not seem nearly as fine as it is now.

The sentimental allure of old technology is real, and telling people that something that’s been a part of their daily life for decades needs to be replaced can be hard to distinguish from a personal attack.

2. New technologies often spark cultural shifts towards ease and convenience, which for older generations are hard to distinguish from moral decline.

There is a long history of older generations labeling younger generations as lazy, whining, and immoral.

Baby boomers do this to millennials. A 2009 Pew survey reported: “Seven-in-ten adults say older people have better moral values than the younger generation.”

The book The Greatest Generation shows how baby boomers’ parents viewed their kids. “The idea of personal responsibility is such a defining characteristic of the World War II generation that when the rules changed later, these men and women were appalled.”

Those parents were criticized by their own parents. Fortune magazine wrote in 1936: “The present-day college generation is fatalistic. It will not stick its neck out. If we take the mean average to be the truth, it is a cautious, subdued, unadventurous generation.”

Every generation does this.

Why? Especially given the objective social gains across generations in things like gender and racial equality?

One explanation is that new technology tends to make life easier for those utilizing it, and older generations watching young people avoid the day-to-day grind that they had to endure shake their heads. “You are lazy” is shorthand for “You have technologies that let you avoid the virtue-building hard work I had to experience.”

Cars killed the art of riding a horse.

Telephones killed the art of letter writing.

Cheap goods killed the art of fixing what’s broken.

Email killed phone conversations.

Facebook killed the art of friendships.

Slack killed face-to-face meetings.

Urban life killed the art of living off the land.

All of these innovations can be viewed as social decline and shunned by those nostalgic for how things used to be.

Physicist Max Planck famously said science doesn’t progress by changing minds, “but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Same with new technology. A full embrace often requires waiting for a generation that’s never known anything different.

3. Familiarity is hard to distinguish from utility, so “this is how we’ve always done it” becomes synonymous with “this is the best way to do it.”

Charlie Mugner says “the human mind is a lot like the human egg, and the human egg has a shut-off device. When one sperm gets in, it shuts down so the next one can’t get in.”

Language is an example. Young kids are exponentially better at learning second languages than adults. Part is biology – the part of your brain that processes language stops growing after puberty because it assumes it’s put in its time. But part of this is social. Adults tend to actively study a new language, while kids just play with their friends and learn it subconsciously, which is a more pliable and impressionable form of learning. Kids also don’t feel the need to master the precise nuance of language. They’re not embarrassed if their conjugations are all wrong or if they use simple words. They run with something new even if it’s not perfect. Not being burdened by mastering one language makes learning a second less intimidating.

Adopting new technology is the same.

If you’ve taught a five year old how to use an iPhone and then watched a 65 year old struggle you know what I’m talking about. Adults have a hard time with new technology because when you’ve spent your life mastering say, voicemails, texting feels intimidating and like a waste of time. Adults have a low tolerance for looking incompetent and have faster alternative methods for getting stuff done. Kids, on the other hand, are just happy to play and feel like geniuses when they make an app light up. So the bar to try something new is much lower.

When what’s familiar feels like what’s best, the adoption rate of new technology faces a generational stall.

Sometimes it’s more than generational. Alternative colleges and MOOCs are smaller today than many envisioned a decade ago because the social custom of going to a traditional college – cost be damned – is so culturally familiar.

4. Grasping the value of new technology requires imagination. But unless you have skin in the game that doesn’t seem worth the effort because technology is supposed to make things easier and simpler, not wrack your brain.

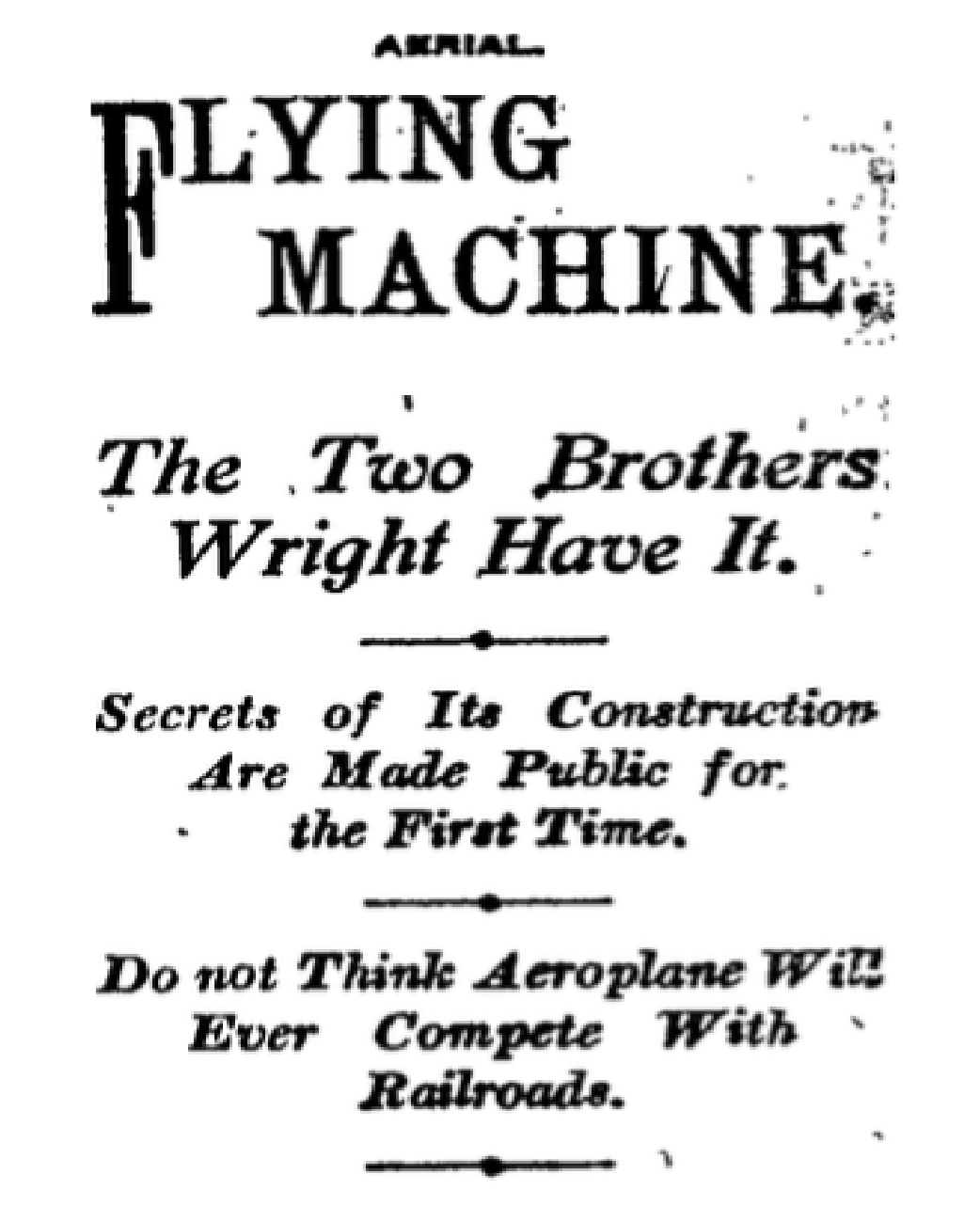

It took about five years for people to pay attention to the Wright Brothers’ plane.

Here’s one of the first mentions, in the LA Times, on May 29th, 1908. I love the line, “Do not think aeroplane will ever compete with railroads.”

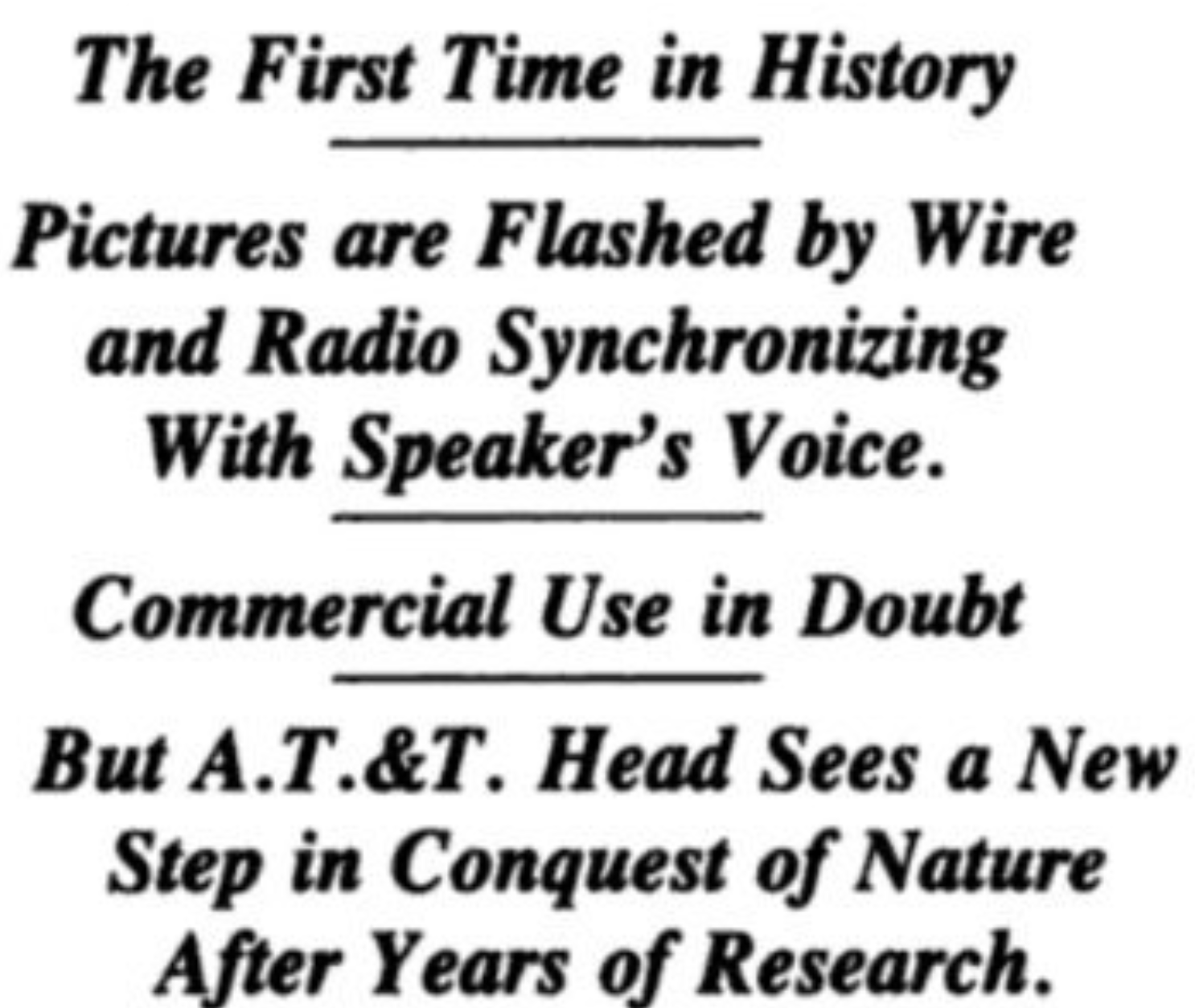

The same happened with the TV. Here’s The New York Times in 1927. “Commercial use in doubt.”

We can look back at both of these and blame a failure of imagination.

But I also don’t think we can blame people for failing to imagine.

Technology is supposed to make your life easier and more efficient. A lot of new technology doesn’t at first. You have to imagine a day when it’ll be better. Entrepreneurs and investors may be willing to do that, but most consumers aren’t. If a new technology confuses them, requires a learning curve, adds risk, has a poor user interface, or requires piecing together several pieces of technology to make it work, of course their imaginations stall. You can’t blame them.

Sometimes entrepreneurs can’t understand why others can’t see the future they do. The answer is often that people without skin in the game are not in the future business; they’re in the today business. It’s easy to underestimate how little thought people are willing to put into a new technology before it becomes an unacceptable mental burden over what they’re already using.

Jonas Salk didn’t have to wait before his polio vaccine become beloved. He wasn’t in it for the money, but the adulation he received was nearly instant. He was on the cover of TIME Magazine within days of his “product” launching.

It’s easy to overlook how rare that is, and how long it takes for people to welcome into their own lives what seems so obvious to you. Creativity, engineering ability, and leadership are all great traits of entrepreneurs. But none matter without the endurance and patience necessary to see it through.