What I Learned in the Last year

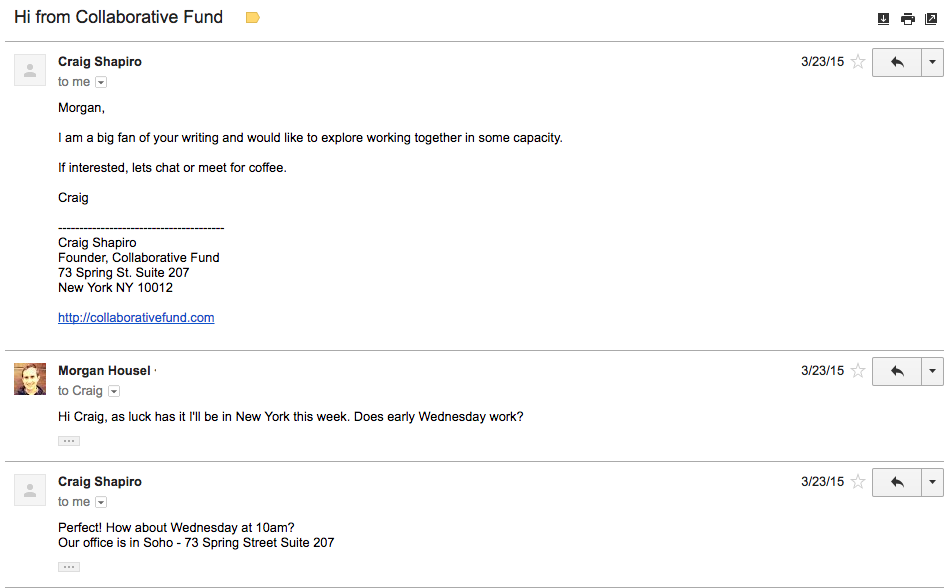

This is how it started:

A short backstory.

In college my plan was investment banking. That’s all I wanted to do. But investment banking’s culture borders on sadism, which turned me off after six months in the field. I got a job in private equity, which I loved. Then credit markets froze, so I needed something else to do. A friend wrote for The Motley Fool, and suggested I try the same. I had never written before – I was a disaster in high school, and majored in economics in college, where writing my name sufficed. But I loved investing, and writing about it seemed fun. I figured I’d do it for a few months; ended up staying nine years. Toward the end I thought I’d stay forever. But meeting Craig two years ago opened my eyes to an investment world that was instantly appealing.

I joined Collaborative Fund a year ago this week.

It’s been an amazing year, with more learning than the previous several years combined. Some weeks feel that way, actually.

A common question I get is, “What have you learned?” Or, better, “How does what you’ve learned compare to what you used to believe?”

Three things stick out.

1. VC deals often lack data, which forces you focus on the behavioral element of business and investing.

People who lose their vision gain greater sense of hearing and smell. The lack of data in VC does the same thing to an investor’s sense of the human and behavioral side of investing. It forces your attention to things like the personality characteristics of a company’s management team, customers’ emotional response to products, and whether you, the investment team, can truly work together as partners vs. the detached guidance of a strategy backtest.

It’s a skill that’s becoming more important. As data becomes commoditized, behavioral intelligence becomes a deeper source of competitive advantage. (This is true in most fields, not just investing). Warren Buffett can perform DCF calculations in his head in seconds. The best VCs can size up someone’s competency and propensity for BS in seconds. Equally important skills.

I wish we had more data. But public investors are blessed with so much data that they often lose sight of the human side of the investing that VCs are forced into. Someone once quipped: “More fiction has been written in Excel than in Word.” Being forced to view the world as it does work, with the messy and counterintuitive dynamics of face-to-face interactions, has a silver lining over those who spend their time calculating how it should work.

2. Start at “no” and work to “yes,” not the other way around.

It’s a heuristic based on two truisms:

-

Decisions in competitive fields must be highly selective among a long list of possibilities.

-

Decisions that eventually work previously looked like bad decisions to other people. The discount from that uncertainty is what drives the subsequent payoff.

If you attempt to whittle down decisions by asking, “I like it but is it possible it won’t work?” the answer will always be “Yes.” If it isn’t, whatever you’re doing will have no payoff for being right. You have to start with default “no” and only act when you identify enough things that could go right. I was terrible at this a year ago.

Craig recently wrote:

Venture investing requires you to suspend reality, focusing on what could go right despite the huge number of things that are likely to go wrong. Those who can’t do this won’t ever pull the trigger, because the number of things that can go wrong is nearly endless.

This applies to many things in life, from careers to relationships. Being sufficiently selective while accepting of the inevitability of things going wrong is a tricky balance. It’s even harder when layered with the requirement of avoiding catastrophic, unrecoverable loss. But it’s the only way to avoid both ignorance and indecision.

3. If venture capital is on one side and public markets on the other, the center of the venn diagram overlaps more than I thought.

Compared to public markets, venture is just a different cut of the same meat. The deal structure is (much) different than public markets. The diligence process is different. But the big principles that guide investment returns don’t change much.

For investors, the psychology of loss and euphoria of gain are identical. For companies, moats and competitive advantage work roughly the same. For markets, the distribution of VC returns is nearly the same as in public markets; the shakeout of winners and losers just happens faster. Those three points explain most of investment returns, so this isn’t small. The areas that are distinct differ mostly by weight alone. Public investors put 90% of their analysis on business and market fundamentals, and 10% on the team and management running the business. VC investors probably flip those numbers.

Realizing how similar fields are that, at first blush, look different opens your eyes up to how many people can help you get better at your job. I’m now more likely to talk to investors who do totally different things, realizing that we’re all swimming in the same pool, even if we’re doing different strokes.

Here’s to more years, and learnings, to come.